History

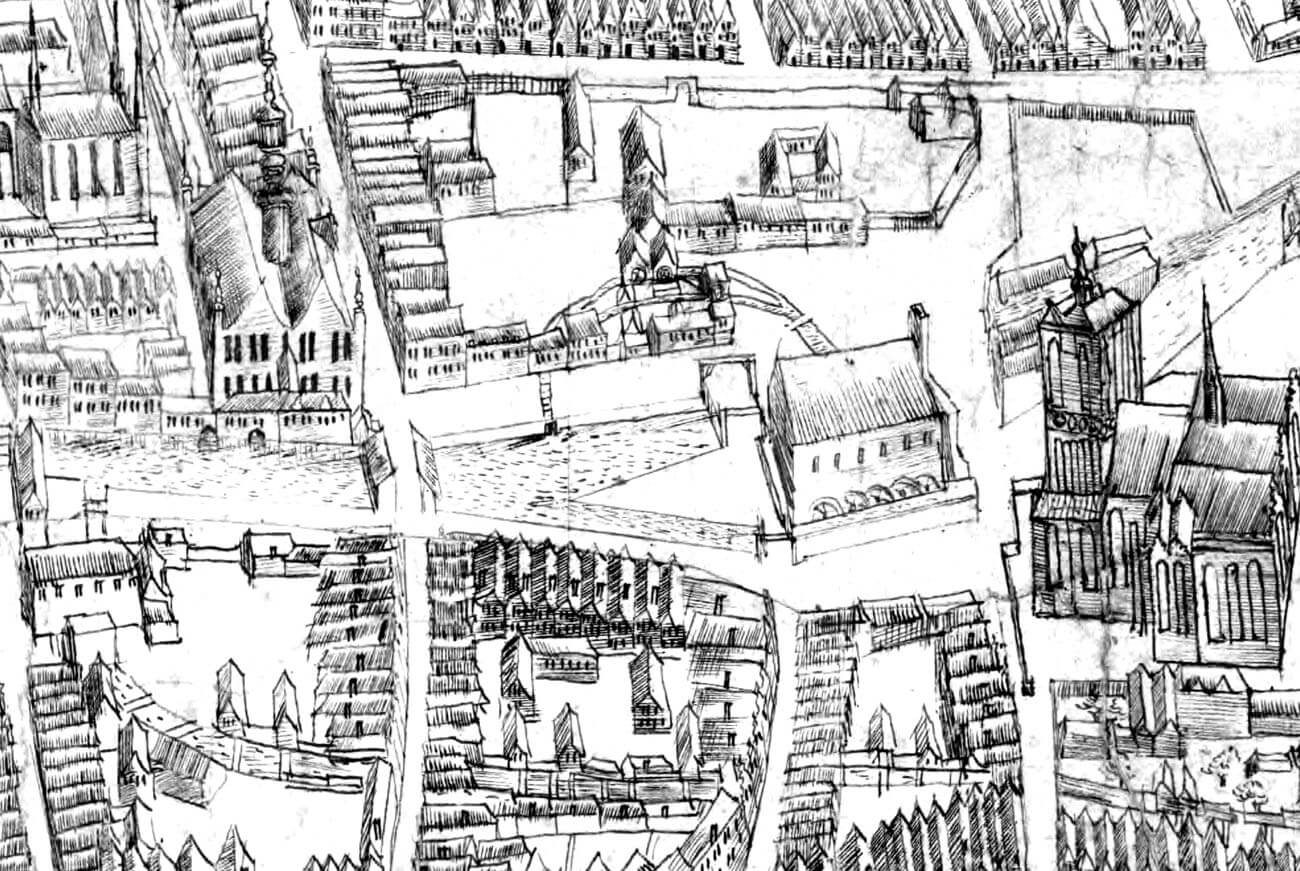

At the beginning of the 14th century, there was probably no grain mill in Gdańsk, because the townspeople used the mill at St. Adalsbert. The Great Mill was built by the Teutonic Knights around the mid-14th century on an artificial island of the Radunia Channel, near a tannery, a fulling mill, a copper forge, a sawmill, an oil mill, a grinding mill and several other smaller grain mills. According to a document of the Gdańsk commander, Ludwik von Essen, the construction of the mill was completed before he took office, i.e. before 1361. The first record of it was made in 1364, but already before 1338, an artificial mill canal was dug near Pruszcz Gdański, passing through the Old Town and flowing into the Vistula. Before 1356, the Teutonic Knights dug a new mill canal running from Orunia (“novum fossatum molendini”), which took over the waters of the Siedlce Stream.

In 1391 the Great Mill burned down, but due to its great importance, it was soon rebuilt. Special fees forced by the Teutonic Knights on service recipients contributed significantly to this. Around 1400, another important water mill was built, called Small Mill, also located on the Radunia Channel in the Old Town. It mainly served as a granary for products from the Great Mill located on the opposite side of the island. Both mills were then managed by a Teutonic official, a Mill Master, who reported to the Gdańsk commander, and sometimes even directly to the Grand Master of the Teutonic Knights. The mill workers (“Moleknechte”) were subordinated to the Mill Master, associated in a brotherhood, first recorded in 1365, when received a special ordinance from the Gdańsk commander, which described the strict rules prevailing in the mill, including obligations and penalties for failure to fulfill them, and the amount of remuneration for work. The ordinance also regulated order regulations, relations between employees and proceedings in the event that the mill’s operation was suspended.

In 1454, Gdańsk townspeople belonging to the anti-Teutonic conspiracy took over the Great Mill without a fight, which initiated an uprising against the authority of the Teutonic Order. From then on, the current mayor of Gdańsk and the first councilor managing finances began to supervise Great Mill and the other city mills. After Poland won the Thirteen Years’ War, King Kazimierz IV handed the mill over to the inhabitants of Gdańsk. From then on, until the end of the Middle Ages and throughout the 16th century, it produced up to 200 tons of flour per day. A group of employees with precisely defined tasks supervised the efficient production then. These included a master of the milling craft, a malt miller, a rye miller, a stonemason, a tribute collector, a lock knecht, a scale knecht, an helper, a cattle grazer and a cook.

In the early modern period the architecture of the Great Mill remained unchanged, but its equipment was modernized. Before 1623, the number of wheels in the mill was increased to eighteen. At the beginning of the 18th century, a horse-operated treadmill was installed, used mainly during wars. In the 19th century, steam turbines were introduced, driving rollers for grinding grain and conveyors for transporting grain and flour. In the 20th century, steam turbines were replaced by electric motors. During World War II, the Great and Small Mill were partially destroyed. Reconstruction was carried out in 1962-1965. In 2016, it was donated to the Amber Museum.

Architecture

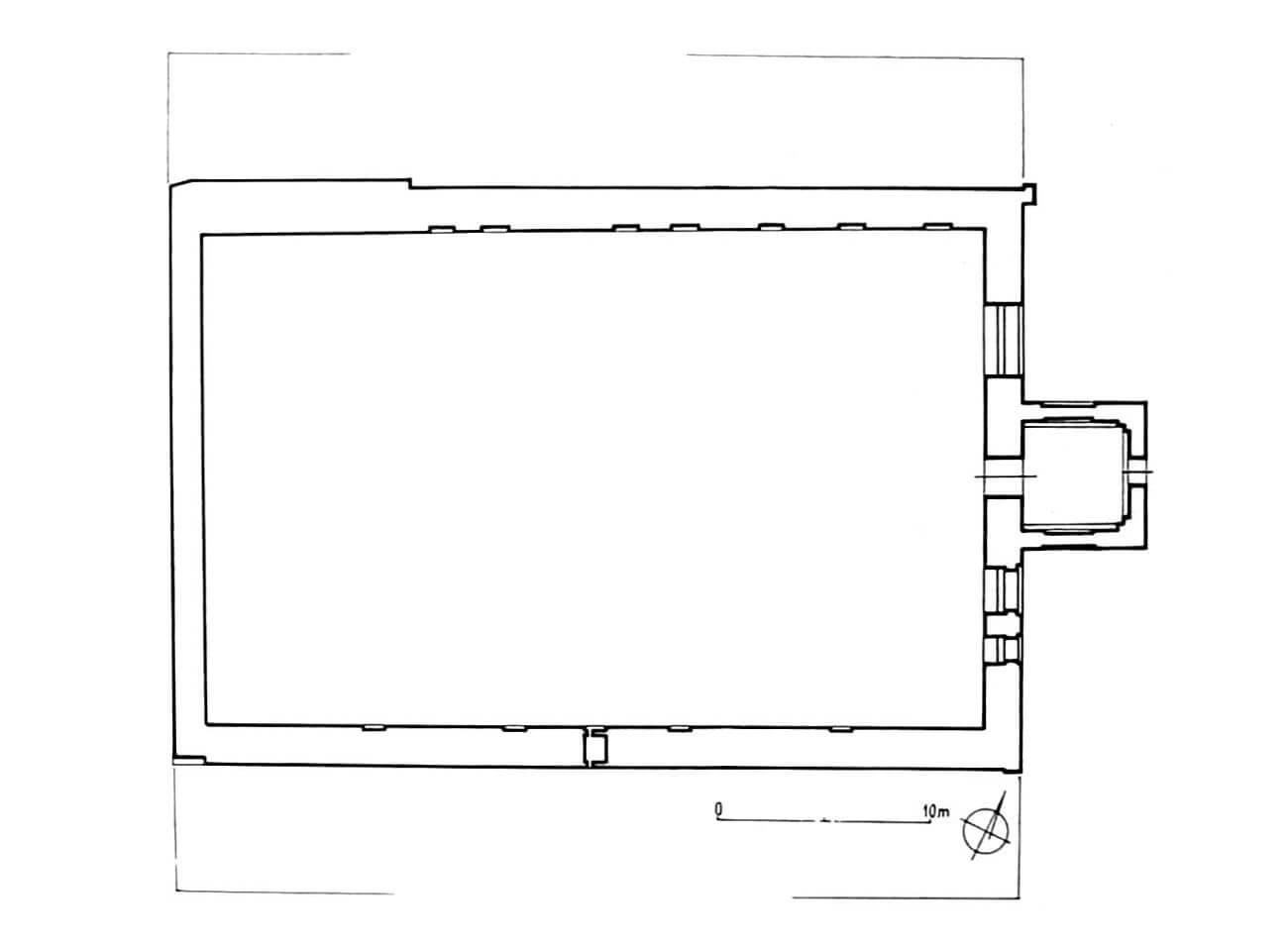

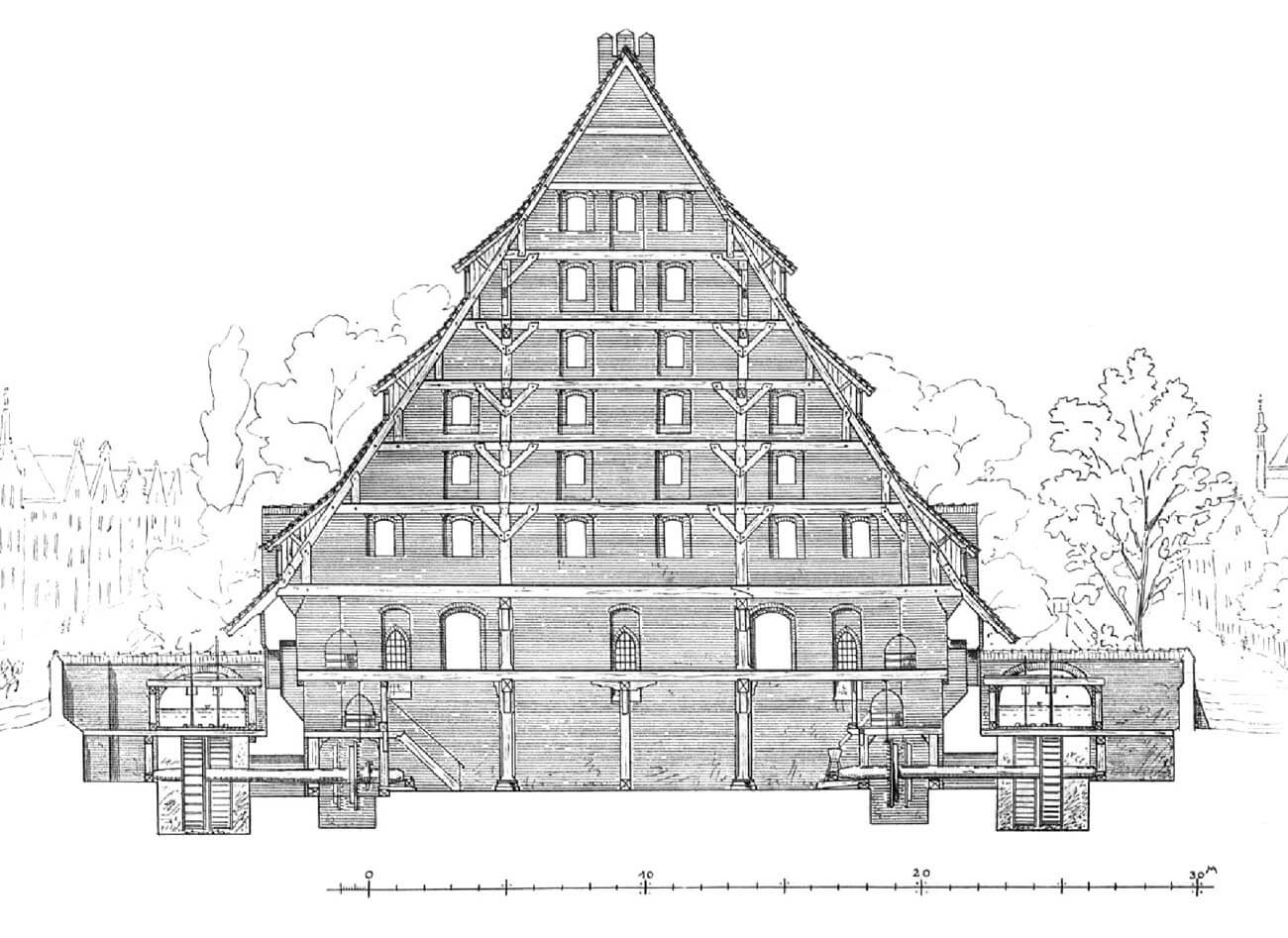

The Great Mill was built near the church of St. Catherine, on a small, artificially created island flowed by the waters of the Radunia Channel. It was one of the largest medieval grain mills in Europe. It was 26 meters high, the same width and 41 meters long. The whole was covered with a high gable roof with steep slopes, supported on triangular gables from the east and west. The building was flowed by water on both sides, which allowed the number of mill wheels to be doubled, thus increasing efficiency. In the Middle Ages the Great Mill had 12 bucket wheels with a diameter of 5 meters, separated by 6 on each longer side. As a result, the processing amounted to 3.5 to 4 thousand lasts of grain per year, which was about 43 m3 per day, assuming work on all days of the week, except Sundays.

The two lower floors of the Great Mill were occupied by mill wheels, while the six upper floors were intended for a warehouse. In the annex to the east, you could bake bread, then sold, among others, on the Bread Bridge at the Old Town Hall. The only decorative elements were manifested in the fragmentation of both gables by narrow, pointed-arched recesses housing windows and in the crowning of the western gable with three brick pinnacles of a very simple form. Around the Great Mill there were also many other buildings, such as stables, bread stalls and the mill manager’s house.

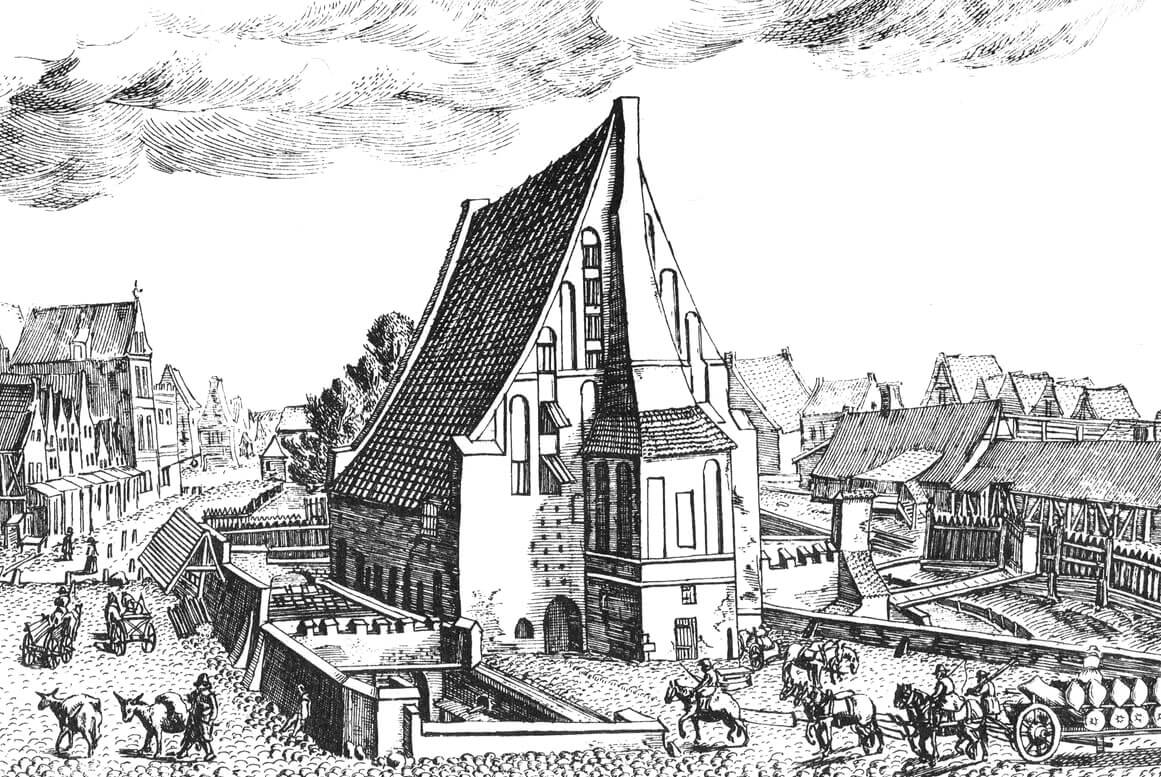

The Small Mill was built on the north-eastern side of the Great Mill, several dozen meters away from it, in the eastern part of the island. Unlike the Great Mill, the Little Mill was located directly above the canal bed, which enabled efficient unloading of boats with goods arriving from the Great Mill. The Small Mill was built as a simple, ridge-shaped building on a rectangular plan with two triangular gables supporting a roof. One of the gable walls was decorated with narrow, elongated pointed recesses housing windows, under which there was a semicircular arcade overlooking the flowing waters of the canal.

Current state

The two Gothic Gdańsk mills, preserved to this day, despite the early modern transformations and depriving them of their original function, are one of the most important monuments of early technology in Poland. Inside the Great Mill, today there is the Amber Museum, while the Small Mill is occupied by offices, so its interior is not open to the public. In the Great Mill, apart from precious stones, you can see two fragments of a stone burr, which was used to grind grain into flour.

bibliography:

Architektura gotycka w Polsce, red. M.Arszyński, T.Mroczko, Warszawa 1995.

Friedrich J., Gdańskie zabytki architektury do końca XVIII wieku, Gdańsk 1997.

Grochowski Ł., Kultura życia w dawnym XV- i XVI-wiecznym Gdańsku – pracownicy Wielkiego Młyna, “Nowa Perspektywa”, nr 2/2016.

Paner H., Rozwój przestrzenny wczesnośredniowiecznego Gdańska w świetle źródeł archeologicznych, “Archaeologia Historica Polona”, tom 23, 2015.

Steinbrecht C., Die Ordensburgen der Hochmeisterzeit in Preussen, Berlin 1920.