History

The Działdowo castle was erected in an area originally called Sasinia. In the thirteenth century it was a depopulated area, overgrown by a forest, heavily marshy. In 1257, the Bishop of Chełmno received Sasinia from the Dukes of Mazovia, and at least from the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries it was already in the hands of the Teutonic Order. Construction works on the castle in Działdowo (Soldau) were to start in 1306, although the first fortifications were probably in the form of a small watchtower. Its role increased after marking the border between the Teutonic state and Mazovia in 1343 at the convention in Bratian, because the colonization action in the vicinity of Działdowo intensified then. The final settlement of the issue of belonging of the surrounding areas to the Teutonic Order and the establishment of economic and population base gave the possibility of building a brick castle at the beginning of the 1440s. It was recorded for the first time in 1343, when the Grand Master Ludolf König, while in Działdowo, gave Nicholas Megirlin 50 ha of land on the Szkotówka River. In 1343, the castle house in Działdowo was recorded again, a year later a town was founded nearby, and in the foundation act the Grand Master allowed the townspeople to fish in Nida below the castle (castrum).

Initially, the castle in Działdowo was subordinate to the Ostróda commandry, as the seat of the Teutonic pfleger. The official was recorded for the first time in 1350 as a witness when the privilege was granted to the village of Kisiny. Brother Kunemunt Malsleibe resided in Działdowo at that time, and his deputy was Ludwig von Brandenburg. In 1383, Działdowo was raised to the rank of the vogt’s office, and the first Teutonic vogt, Hensel von Lichtenstein, was directly subordinated to the Grand Master. At the beginning of the 15th century, the vogt of Działdowo included 12 or 11 rental villages, 20 Chełmno estates and 11 estates under Prussian law. In addition, there were also the town of Działdowo and a farm in Księży Dwór, perhaps a farm in Tylków, as well as castle mills and at least 7 other mills located in the surrounding villages. So the Działdowo district was of average size, which contrasted with the magnificent form of the castle. Its extended shape was probably the result of its location in the border area near the crossing of the narrow Nida valley, where Masovian and Teutonic conventions often took place, and thus it was often visited by senior representatives of the order. For example, in 1389, an agreement was signed at the castle between the Teutonic Order and prince Janusz I, regarding the prosecution of criminals and the exercise of jurisdiction over them, in the same year a date was also set in Działdowo for a peace convention between the order and Lithuania that would not finally come into effect, in 1400 in Działdowo took place negotiations between the representatives of prince Janusz I and the Teutonic commanders of Gdańsk and Ostróda, as a result of which another agreement was concluded in Działdowo, signed by Konrad von Jungingen and Janusz I, in 1403 the Grand Master came to the castle, and a year later Polish Grand Chancellor of the Crown, Mikołaj Zaklika, in 1404 the Grand Master and the Duke of Mazovia stayed in Działdowo, while in 1432 there were negotiations in Działdowo between the Grand Master and his council and Prince Siemowit V. In the provisions of the Brześć Peace of 1435 it was written that the border courts between the part of Mazovia ruled by Władysław I would be held alternately in Działdowo and Mława every year, while in the conditions of the Masovian-Teutonic truce of 1459 it was written that conventions resolving disputes between the principality and the Teutonic Order will take place every year alternately in Działdowo and Janowo.

The castle was repeatedly the subject of fights between the Teutonic, Prussian, Polish and Lithuanian armies. In 1376, Działdowo was destroyed by the Lithuanians of prince Kęstutis, and the stronghold was then burnt, at least partially. It was during the reconstruction that a decision was made to create a vogt office in it. In 1410, during the march of Jagiełło’s army to Grunwald, the castle was one of the first to be occupied without a fight. Działdowo was handed over to the Duke of Mazovia, Siemowit IV, who appointed his starost at the castle. Soon after, however, the local nobleman Piotr of Sławkowo recaptured the castle, asking the Teutonic Knights to send a crew. Again, the Poles seized the stronghold in 1414. Perhaps, in connection with these war events, in 1419 Master Hannus conducted unspecified carpentry work at the castle. The next seizure of the castle by Poles took place in 1422, and the castle was stormed also in 1439. During the Thirteen Years’ War, Działdowo changed hands several times, and during one of the sieges, the Teutonic commander of Vienna died there. When the conflict broke out, the stronghold was in the possession of insurgents from the Prussian Union. In February 1455, it was temporarily taken over by the Teutonic Knights, burning the town, and then recaptured by the insurgents under the command of Jan Kloda. Definitely, the Teutonic Order recaptured the castle only in 1460.

After signing the Second Peace of Toruń in 1466, the castle remained within the borders of Ducal Prussia. It suffered heavy losses in 1520, during the last Polish-Teutonic war. After a long, nine-week siege, Działdowo was then conquered and destroyed by the army of King Zygmunt, and then handed over to Piotr Kryski, the castellan of Płock and the tenant of Mława. Presumably, the last siege caused further damages to the castle, which were removed after the final defeat of the Teutonic Order and the secularization of Teutonic Prussia, when Działdowo became part of the Duchy of Prussia.

In 1525, as a result of the secularization of the Teutonic Order, the castle became the seat of the prince’s starost. It lost its importance then, as it ceased to be a facility serving the central authorities of the order and no longer guarded the enemy border (the feudal principality was surrounded by allied Poland). However, it was well kept, and due to its location near hunting grounds, it was planned to create in it the ducal residence of Albrecht Hohenzollern, used because of its location on the route from Königsberg to Kraków. It was also frequented by Warmia and Chełmno bishops, as well as royal and princely officials of various levels. In Działdowo, the Polish plenipotentiaries were also handed the annum, i.e. the fee paid annually by the Duchy of Prussia to defend the borders of the Kingdom of Poland.

In the years 1541-1588, numerous renovation works were carried out in the castle, individual rooms were rebuilt, especially in the outer ward, new buildings were erected, and the old ones were demolished. In 1541, the drawbridge and the roof were to be repaired and a malt house built, in 1549 the old bathhouse was demolished and the well roofing was renovated. Work began on the construction of a water supply system, completed around 1552 with the roof covering the water tower. At that time, the carpenter from Königsberg, master Blasien, probably built the so-called long stable. After several years of minor construction and renovation works, in 1567 the cylindrical tower was to be raised, the gable was built over the gatehouse and the moat was cleaned. Around 1577-1578, the gables of the main castle house were transformed, and in the following years, roofers and craftsmen repaired mainly the roofs and floors of the rooms. The castle underwent further transformations in the 17th century, slowed down only between 1636 and 1677, when the castle and the entire starosty were pledged to Reinhold von Rosen, who did not invest in objects that did not bring him income. In 1668, the building was supposed to be damaged by a storm, and despite this, the owner was reluctant to renovate it. During the pledge period, the castle last served as a residence in 1656, when during the short stay in Działdowo of the Swedish king Charles X Gustav, he received an envoy from Turkey as well as English, Russian and Transylvanian legations.

At the end of the 17th century, after the return of Działdowo to the ducal administration, the castle, despite numerous but never realized plans for reconstruction, never regained its former rank. In the 18th century, it fell into greater and greater ruin, was partially demolished and performed economic functions. Unfortunately, bricks from the castle were used to rebuild the town after numerous fires and to build a new town hall. The castle’s main house was probably saved thanks to transfer in 1711 the Evangelical commune, which housed the pastor’s apartment in it. Further destruction and devastation were brought by the occupation forces of Napoleon in 1806 and the fire of the castle from 1868, while the first renovation works were undertaken at the beginning of the 20th century.

Architecture

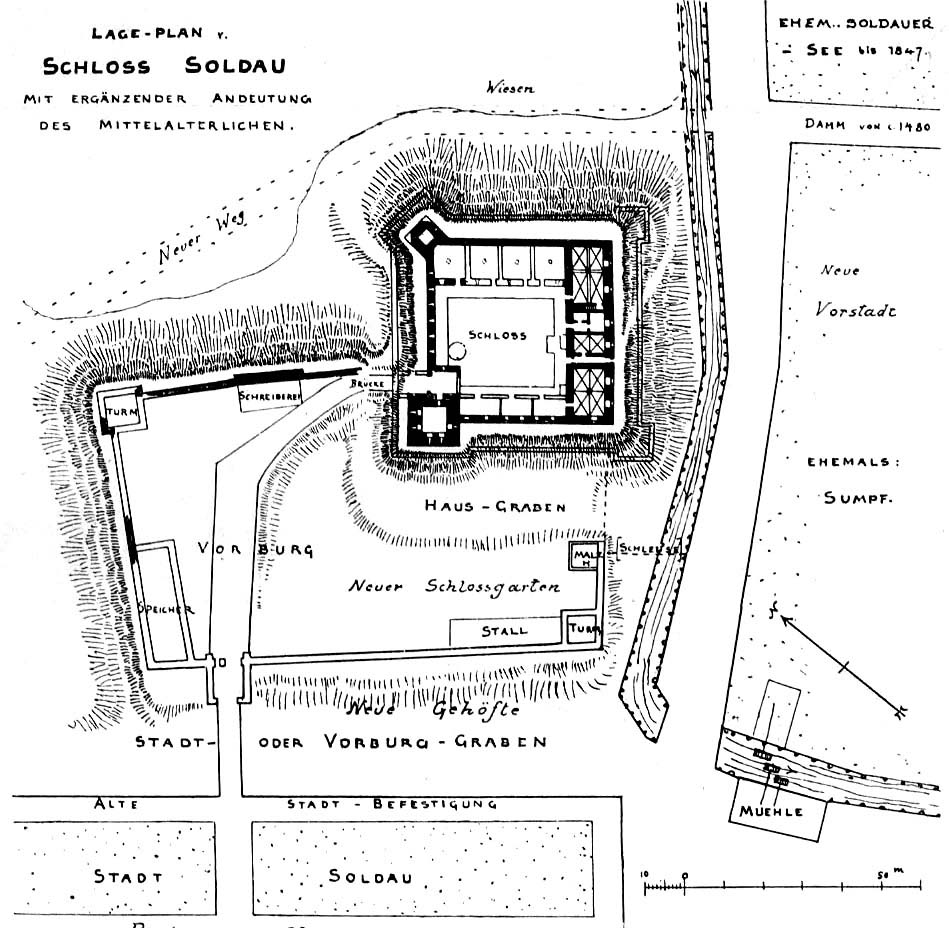

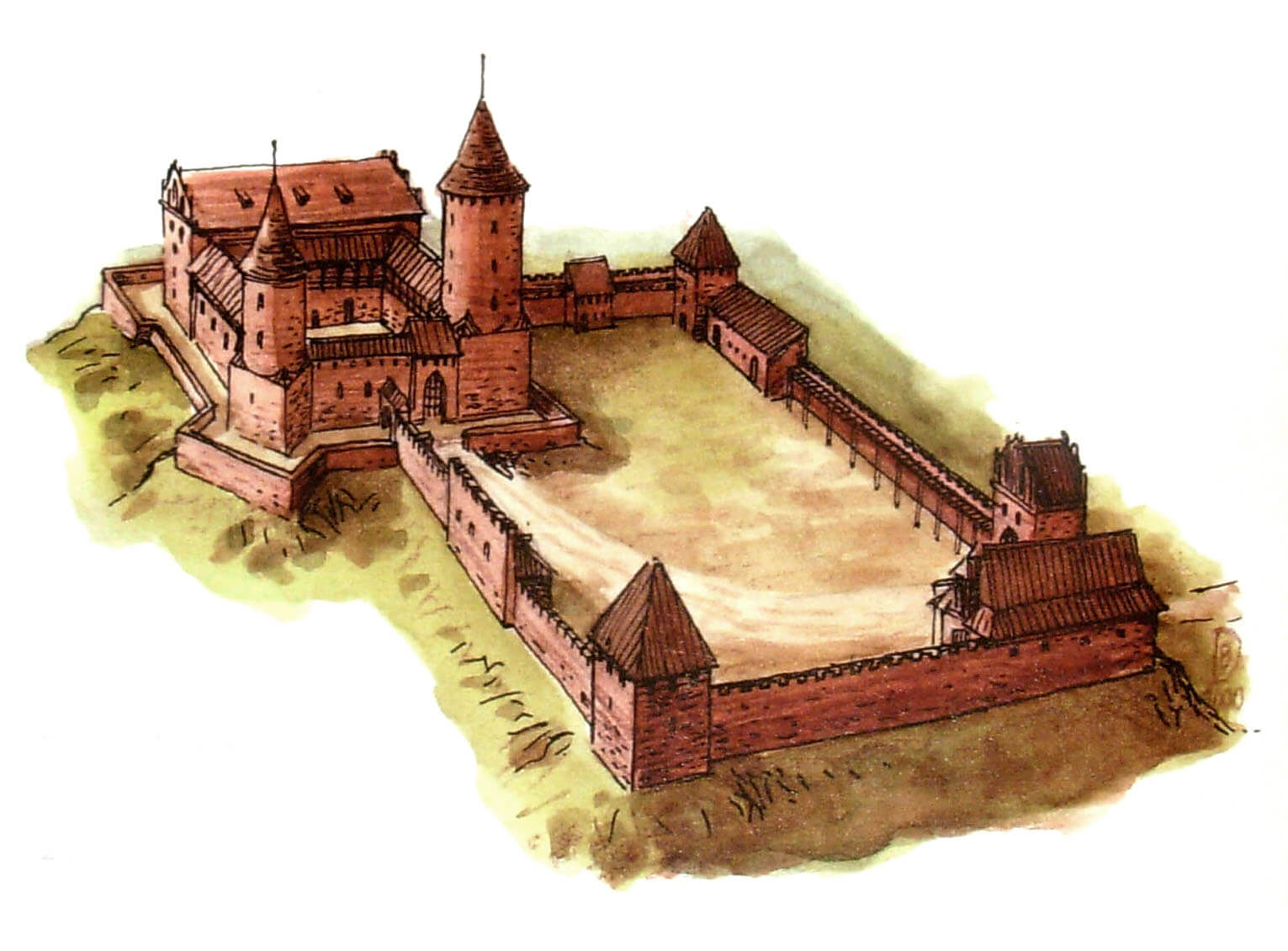

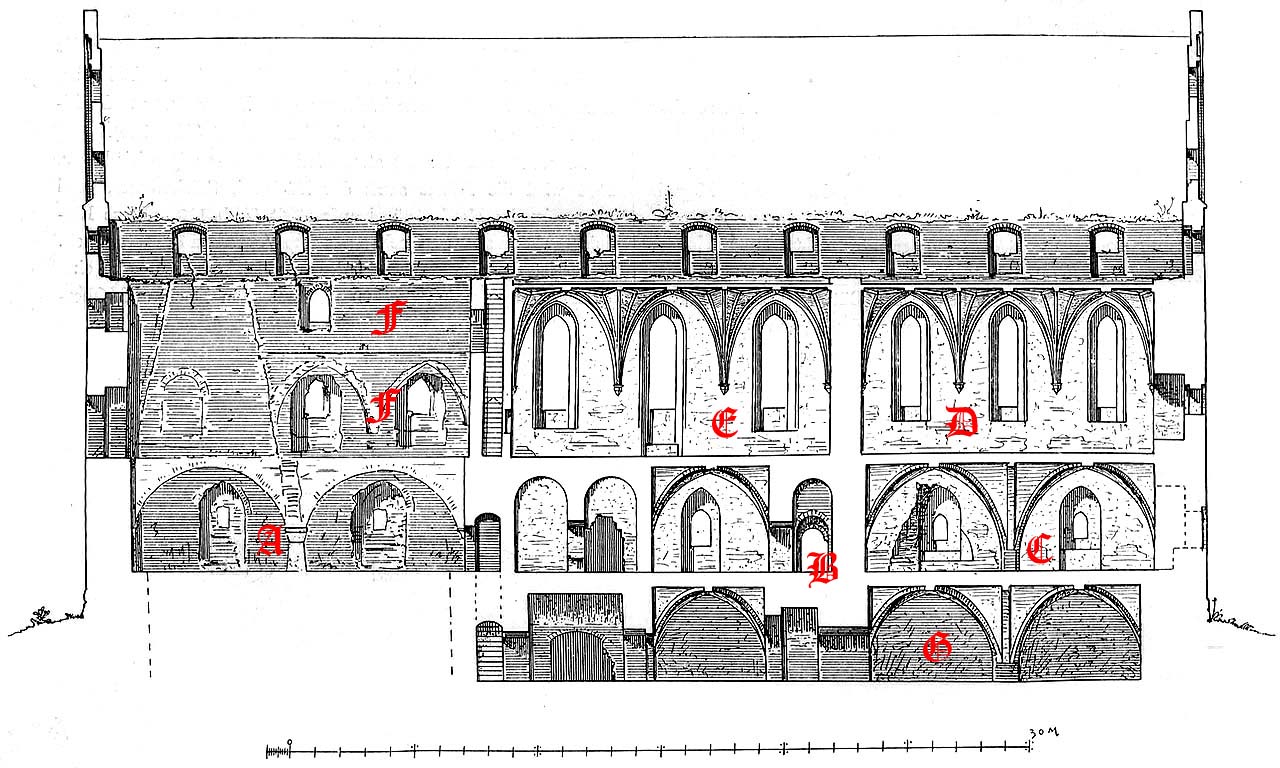

The castle was located on the northern edge of a marshy valley, on a small hill, surrounded on three sides by wetlands and the nearby Działdówka river, next to the mouth of an unnamed stream. On the fourth side (west), the only one dry, flat and providing easy access, a fortified town developed over time, built on a rectangular plan and separated from the outer bailey by a moat. In addition, at the foot of the castle hill, a canal was dug to supply water to the mill, along which a road connecting the town with Nidzica and Mazovia ran along the dike. Thanks to this, the castle was able to control the only passage across the river on a long stretch. At the dike, on the south-eastern side of the castle, there was also a settlement called Wola Zamkowa, taken out of the town’s jurisdiction, and around 1480 a causeway was built that crossed the Nida River valley near the village of Kisiny. The latter finally shaped the water system with the great Castle Pond and smaller Middle and Upper Ponds located in the valley of the aforementioned nameless stream. The very core of the castle had a shape similar to a square with dimensions of 46 x 47.6 meters, so it was a magnificent complex for castles of vogts, the second largest in the area of the commandry (after the Ostróda castle).

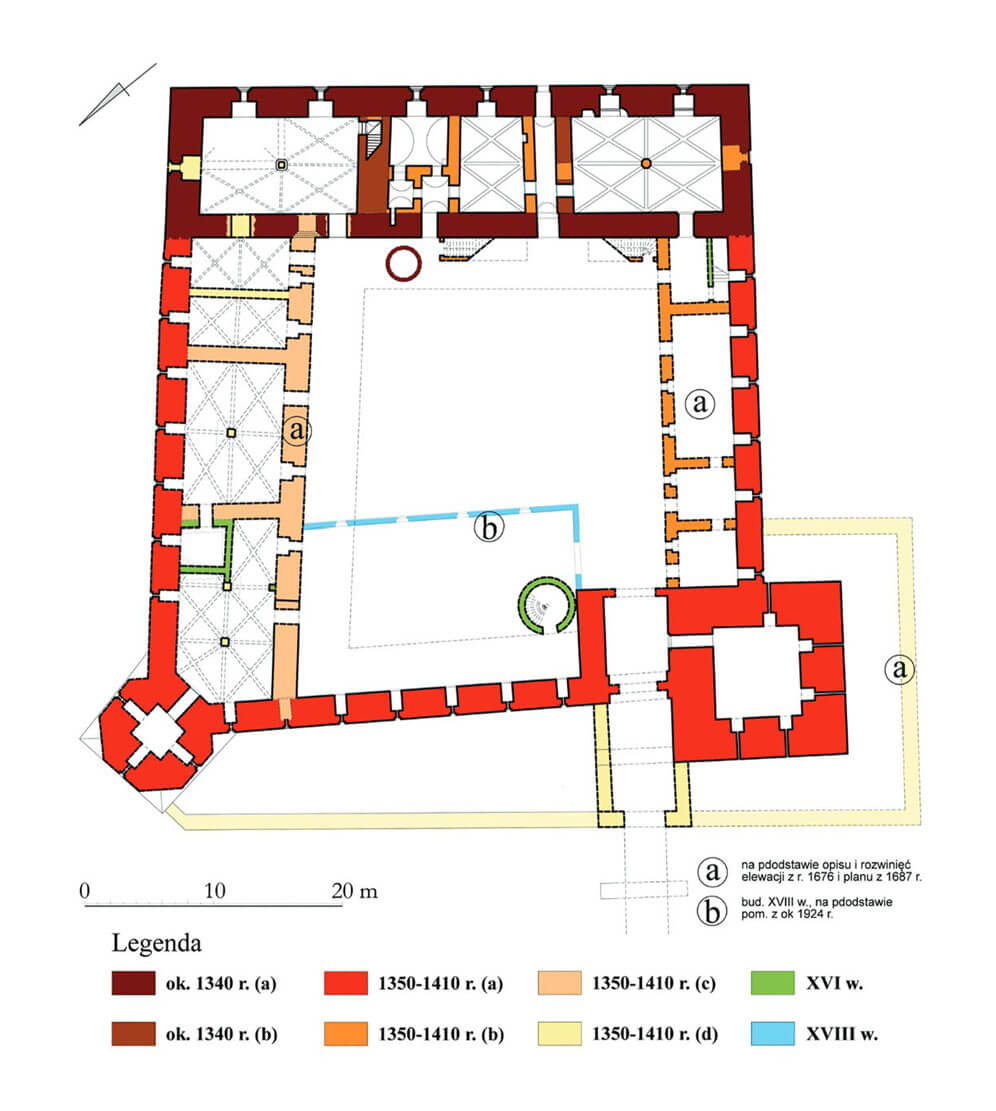

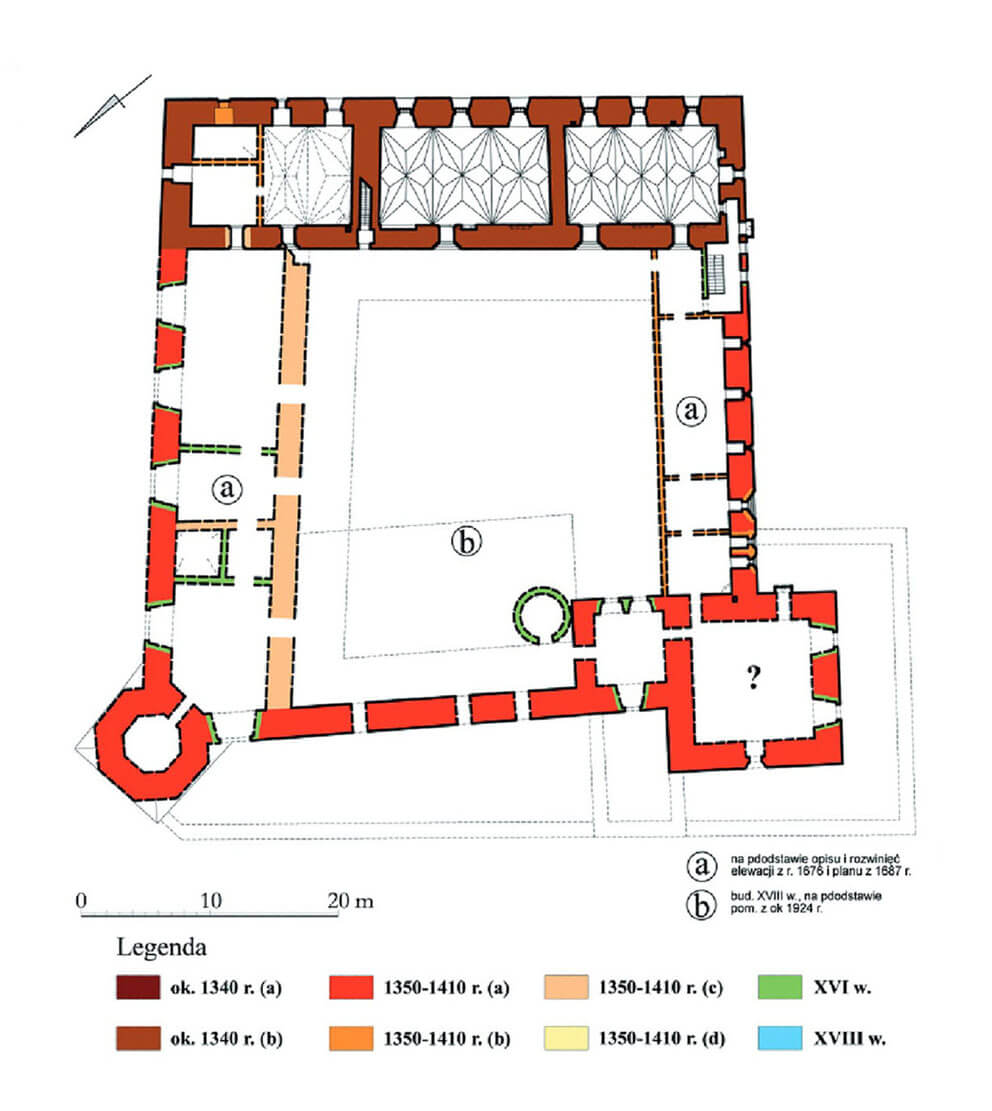

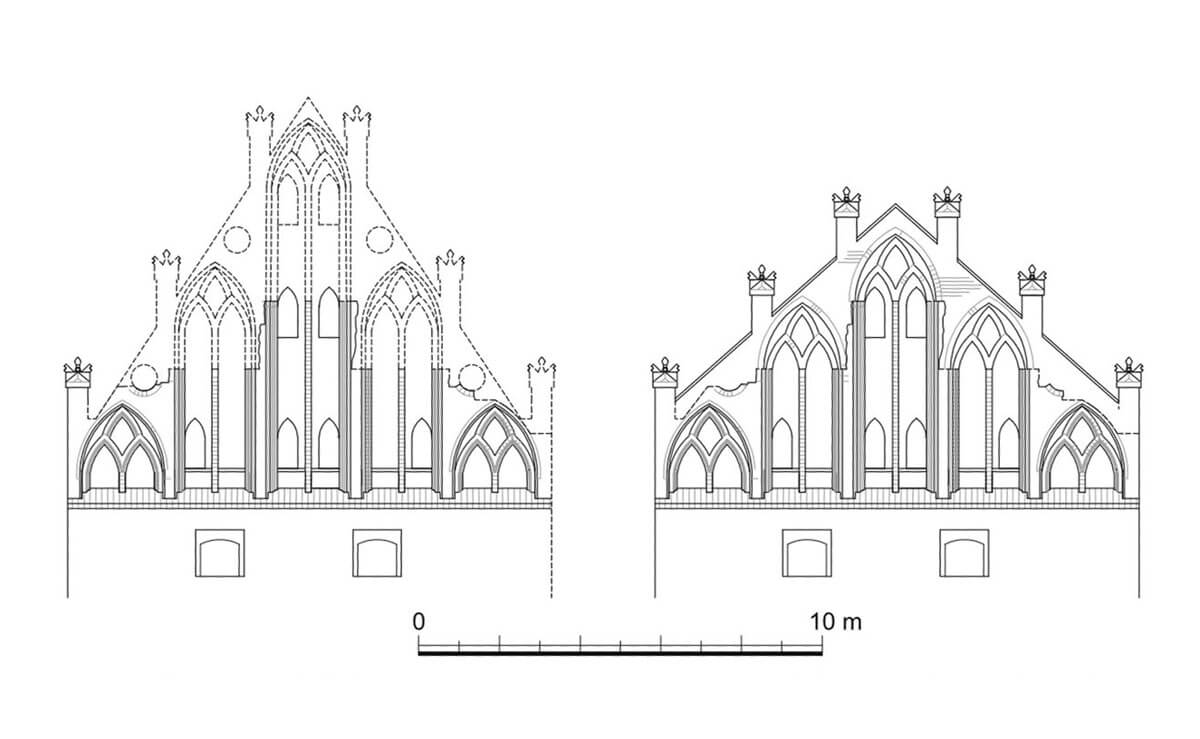

The main residential house of the castle was the south-eastern range, about 12 x 46 meters, built of bricks on foundations of erratic boulders, buried in the ground about 5.5 meters. It had a basement, ground floor rooms and two floors, although the second floor was made only in the eastern part of the building. Probably in the mid-fourteenth century, the rooms of the basement and the ground floor of the main house received vaults, made differently than originally assumed (in one of the rooms, the supports for the initially planned vaults were never used). This forced, inter alia, bricking up the ground floor window in the south-west elevation, or the door between the water postern and the western room. Since the above floors with large windows in the south-eastern facade were not adapted to defense, probably in the third quarter of the fourteenth century the building was raised by one more, top floor with a defensive porch. Decorative, steep gables situated at the shorter sides of the building were also built at that time. They were articulated with five pointed blind niches with tracery decorations made of ceramic fittings. Above the blind niches, round openings (wind holes) or blendes shifted in relation to the axis of the pointed blendes were created.

The house elevations were basically devoid of decorative elements. Only the high windows of the chapel and the refectory as well as the window of the living room were framed with moulded bricks forming a single shaft. They were secured with iron bars against intrusion. The other ground floor and first floor windows had a single order made of non-moulded bricks, while the granary storey windows closed with a segmental arch were placed in rectangular blendes.

Out of the six Gothic entrances to the building, two leading to the outer ground floor rooms were simple, pointedly ended, stepped portals without moulded jambs. The portals of the first floor received brick jambs with a roller-shaped moulding, additionally decorated with green glaze. Two of them led to the refectory, one to the chapel and one to the living room. The most decorative, four-stepped ones, led to the chapel and the refectory, the entrance to the administrative chamber and the side entrance to the refectory had only three orders. Internal orders in the portals, apart from the main portal of the refectory, were closed with segmental arches, thanks to which tympanums were created above the entrances, the interiors of which were covered with plaster and possibly painted decorations.

The basement of the main house was used as a warehouse (mainly for drinks, mostly beer). They were located in the central part of the house, divided into several small chambers, and in the southern part, where a total of four bays were covered with cross vaults based on the central pillar. Their massive ribs and rectangular bays were typical for vaults used in storage and utility rooms in Prussian castles erected from the second half of the 14th century.

The ground floor, traditionally for the Middle Ages, served economic functions. In its north-eastern part there was a kitchen with a cross-rib vault based on one pillar and nine corbels. At the beginning of the 15th century, a large bottle-shaped stove chimney was made in it, which was associated with bricking up two windows in the south-east elevation and one in the north-east elevation. A similar room of unknown purpose was located on the south side. Its vault was based on a polygonal pillar. In the central part of the ground floor there were smaller rooms with cross-rib and barrel vaults, there was also a water postern, i.e. a passage through the width of the entire building to the back of the castle at the moat.

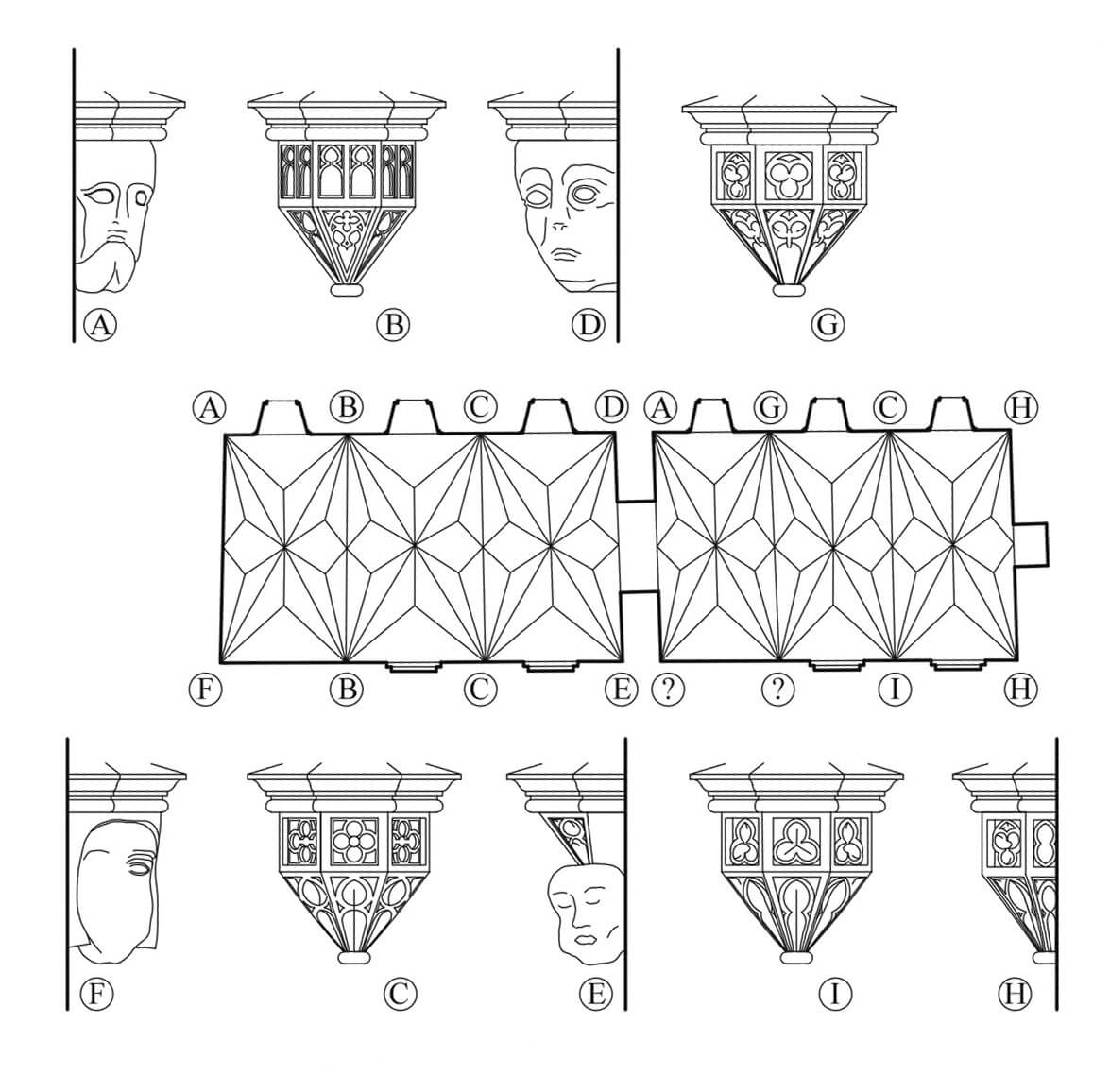

On the first floor of the main house, there were three representative rooms, vaulted from the beginning of the 15th century: a three-bay chapel, located quite unusual for Teutonic castles in the middle of the range, and a three-bay refectory located to the south. The northern chamber was divided with a wooden ceiling, which made possible to arrange the office downstairs, and the vogt’s apartment upstairs. The chapel and the refectory were topped with stellar vaults based on tracery and mask corbels. These rooms received three narrow, pointed windows and decorations in the form of wall polychromes (including a painted coat of arms from the second half of the 15th century). For the convenience of the residents, the floor was heated with hot air supplied through channels from hypocaustum furnaces.

The top floor served as a warehouse and for defense; it was single-space and had small windows or loop holes. Narrow stairs led to this storey, placed in the thickness of the wall between the chapel and the office. In addition, one flight of similar stairs connected the basement with the ground floor, The basement could additionally be accessed via flights of stairs adjacent to the north-west facade of the building, and all rooms on the ground floor were accessible through portals leading straight from the courtyard. The rooms on the first floor were reached through portals from the external, wooden porch. Moreover, in the western corner of the first floor, a passgae to the curtain was made in the wall thickness of the main house, later used to reach a latrine or a small dansker.

The entrance to the castle led through the north-west gatehouse with a foregate, acting as a bridgehead of the bridge supported by five brick pillars, placed over a nine-meter-wide moat. The gate was in the vicinity of the western, corner, massive tower, similar in plan to a square with dimensions of 13.4 x 13.5 meters, protruding from the perimeter of the walls. The tower had two storeys of cellars and its foundations extended over 8 meters below the level of the courtyard. According to some researchers, it had an octagonal superstructure. In its lower basement, due to the judicial duties of the vogts, there was a prison, accessible through an opening made in the cross vault. The upper basement was covered with a beam ceiling, although the builders of the castle planned to vault it. The ground floor and the upper floors of the tower were also covered with ceilings and connected with the gatehouse. The walls of the ground floor were pierced with a total of five arrowslits, and the first floor from the north-west with a single ogival window. The northern corner of the castle was reinforced by a smaller tower, built on a square plinth, turned by 45° in relation to the adjacent curtains, passing higher into an octagon, topped with a cylindrical superstructure.

The south-west and north-west walls closing the courtyard had three levels of arrowslits. Those located in the lower one were accessible from the courtyard level, the middle floor, analogous to the lower one, was accessible from a wooden porch suspended on the wall, while the highest one, with a different pattern of arrowslits, was made in a thinner wall and accessible from the porch on the wall offset. The form of the north-eastern wall probably in the lower parts was similar to the others.

In the fourth quarter of the 14th century, an originally unplanned, two-story north-east wing was built, initially covered with a mono-pitched roof based on a higher wall. The front wall of the new building was added to the wall of the main house in such a way that it obscured the two portals leading to it, one on the ground floor, the other on the representative floor (this forced a new door to the eastern room of the main house’s ground floor, one leading from the courtyard, the other on the axis of the ground floor of the new wing). On the opposite side, one of the arrowslits was covered in a similar way. In the initial phase, the ground floor of the north-east wing was divided into three rooms of unequal size, of which the south-east and central ones were clearly shorter. At the beginning of the 15th century, the south-eastern room was divided with a partition wall and vaulted on six granite corbels in the form of inverted cuboids. The ground floor of the wing could have economic functions, while the first floor may have housed rooms intended for frequent guests of the Teutonic Order.

Around the fourth quarter of the fourteenth century, a narrow, two-storey south-west wing was also built, covered with a gable roof with asymmetrical slopes (larger on the courtyard side). Together with the opposite one, it had economic and residential functions, which would be indicated by relatively large Gothic windows, with jambs of moulded bricks, located in its western part on the first floor (a secular castle crew could live in it). The inner courtyard was surrounded by the aforementioned wooden porches, installed in the openings left in the walls at the façade of the main house and at the north-east wing, providing access to the portals on the first floor. There was a well in the courtyard, located near the former kitchen. The main castle was surrounded by an additional, external defensive wall, separating the zwinger, and the aforementioned moat.

On the west side of the upper ward there was a spacious outer bailey. It was of an economic nature and was surrounded by separate fortifications. There were, among others, stables, a granary and a malt house. The defense was provided by simple curtains of the walls, reinforced with a four-sided tower in the northern corner, slightly protruding in front of the face of the adjacent curtains, and a slightly smaller southern tower located completely inside the courtyard. The gatehouse was located near the north-west corner of the outer bailey, it was almost entirely extended towards the moat. A building inextricably linked with the functioning of the outer bailey, though not within its walls, was the castle mill, located on the southern side, between the outer bailey and the town.

Current state

The south-east wing of the castle has survived to the present day, i.e. the main residential house and partially the north-east range and relics of other elements of the upper ward. Among the architectural details, the gables of the main house are extremely valuable, which, although partially rebuilt in the 16th century, are one of the few surviving gables of the Teutonic Order castles. In addition, several portals, window openings, rib and stellar vaults with their support system have survived (of the latter, only the lower parts are original, the remaining parts have been renewed). Unfortunately, the castle in Działdowo is one of many examples in Poland, where it was decided to mindlessly destroy the immediate surroundings of a medieval monument. The west wing and the south-west tower were built up with modern, ugly and detached from the historical context buildings, in which the City Hall was located. In 2018, the main castle house was renovated, and it was converted into the seat of the Borderland Museum in Działdowo.

bibliography:

Garniec M., Garniec-Jackiewicz M., Zamki państwa krzyżackiego w dawnych Prusach, Olsztyn 2006.

Leksykon zamków w Polsce, red. L.Kajzer, Warszawa 2003.

Steinbrecht C., Die Ordensburgen der Hochmeisterzeit in Preussen, Berlin 1920.

Sypek A., Sypek R., Zamki i obiekty warowne Warmii i Mazur, Warszawa 2008.

Wółkowski W., Zamek w Działdowie, dzieje budowlane i problemy konserwatorskie, Warszawa 2021.