History

Dominican friary with the church of St. Michael the Archangel, according to the tradition written by the chronicler Jan Długosz, was founded in 1264 by Kazimierz I, prince of Kuyavia. The first confirmed reference to the Dominicans concerned only 1294, when Władysław the Elbow-high, giving the property to the planned hospital foundation in Brześć Kujawski, undertook to protect it from “fratrum praedicatorum strepitibus ac aliis invasoribus”. The bringing of the Dominicans from the Kraków friary, however, could have happened a bit earlier and be related to the foundation of Brześć before 1250, because the foundations of the mendicant monasteries were often indirectly related to the process of the formation of towns. In addition, the monks aimed at an regular distribution of their seats, and the Brześć foundation could be associated with the second wave of founding Dominican monasteries, dating back to the 30s and 40s of the 13th century. At that time, Dominican seats were established in such cities as: Brno, Olomouc, Poznań, Sieradz, Racibórz, Chełmno and Elbląg.

The Brześć friary was probably a wooden structure at first, located in the area of Old Brześć, near its town fortifications. It was destroyed along with the entire town in 1332 as a result of the Teutonic Knights invasion. The then Dominican prior, Piotr called Natura, testified at the Warsaw-Uniejów trial in 1339 that the church and friary were destroyed with the help of siege machines. In addition, the invaders had to shoot their arrows so intensely before conquering the town that it seemed that it was raining. After the end of the war, the town was translocated to a new location, and for some time it was also economically weak. Therefore, the brick chancel of the Gothic monastery church was not to be funded until 1383. The initiator of this undertaking was Bishop Zbylut from nearby Włocławek, and construction works had to be carried out on the church from the 70s of the 14th century. After 1383, the construction of the nave began, but this investment had to be suspended due to the battles for the Polish crown, namely the related temporary occupation of Brześć by the Mazovian prince Siemowit IV. In the same 1383, his army captured and plundered the town, so renovation works were probably a priority. Another delay of construction could have caused the Polish-Teutonic conflict, so that the church was finally completed probably around the beginning of the 15th century. Then, in the second half of the fifteenth or only in the sixteenth century, the sacristy was added.

The friary from Brześć played a secondary role, especially in the late Middle Ages. It could not compare with Dominican monasteries in such cities as Wrocław, Gdańsk, Toruń, Elbląg or Poznań, not to mention the capital city of Kraków. However, all the time it was of great importance for the religious and cultural life in Brześć and its vicinity. Initially, the monks’ livelihood was mainly a collection in their own church during services, as well as the direct care of the Kuyavian princes. With time, however, the brothers from Brześć also began to derive income from estates, which they obtained through donations or purchase. These were the rents for three mills, fish ponds, fiefs and the rental of the refectory for the sessions of the land courts. In addition, the congregation associated with this friary made donations for it. Although the friary did not present a great economic potential, it was an important trade partner, especially for the local population, as evidenced by records in the books of Church and secular courts. The Brześć friary, like the others belonging to this order, was also a base for the activities of the Inquisition, although in Poland it was not extensive. The friary could host Dominican inquisitors, and could also lend the rooms for their interrogations or delegate members of the friary as their assistants. The fact that in the vicinity of Brześć some inquisition activities were carried out is known from the record of 1431, when in the valley near Boniewo, the eyes were gouged out and the nose and ears of an unknown Dominican inquisitor were cut off.

Already in the Middle Ages, the church and wooden friary buildings needed repairs. In 1421, Małgorzata Piechalina, a bourgeoisie from Brześć, bequeathed her property “pro fabrica ecclesie monasterii brestensis”. In 1425, king Władysław Jagiełło issued a privilege granting monks one measure of malt a week from the mill near Brześć, because Marcin, the then prior of Brześć, asked for a new document, as the previous one had burned down (so some room had to be destroyed). In 1462, the Dominicans from Brześć obtained permission from legate Hieronim of Crete to adore the Blessed Sacrament, combined with the indulgence privilege for those who contribute to the renovation of the monastery church, the renovation was also recorded in sources in 1484.

The church and friary suffered damages during the wars with Sweden in the 17th century. After the reconstruction and renovation from the 17th and 18th centuries, it took on a Baroque appearance. The last major reconstruction, during which the nave of the church was reduced, took place after a fire in 1922. There were no Dominicans in the monastery at that time. Their friary was dissolved in 1864 as part of the tsarist repressions after the January Uprising.

Architecture

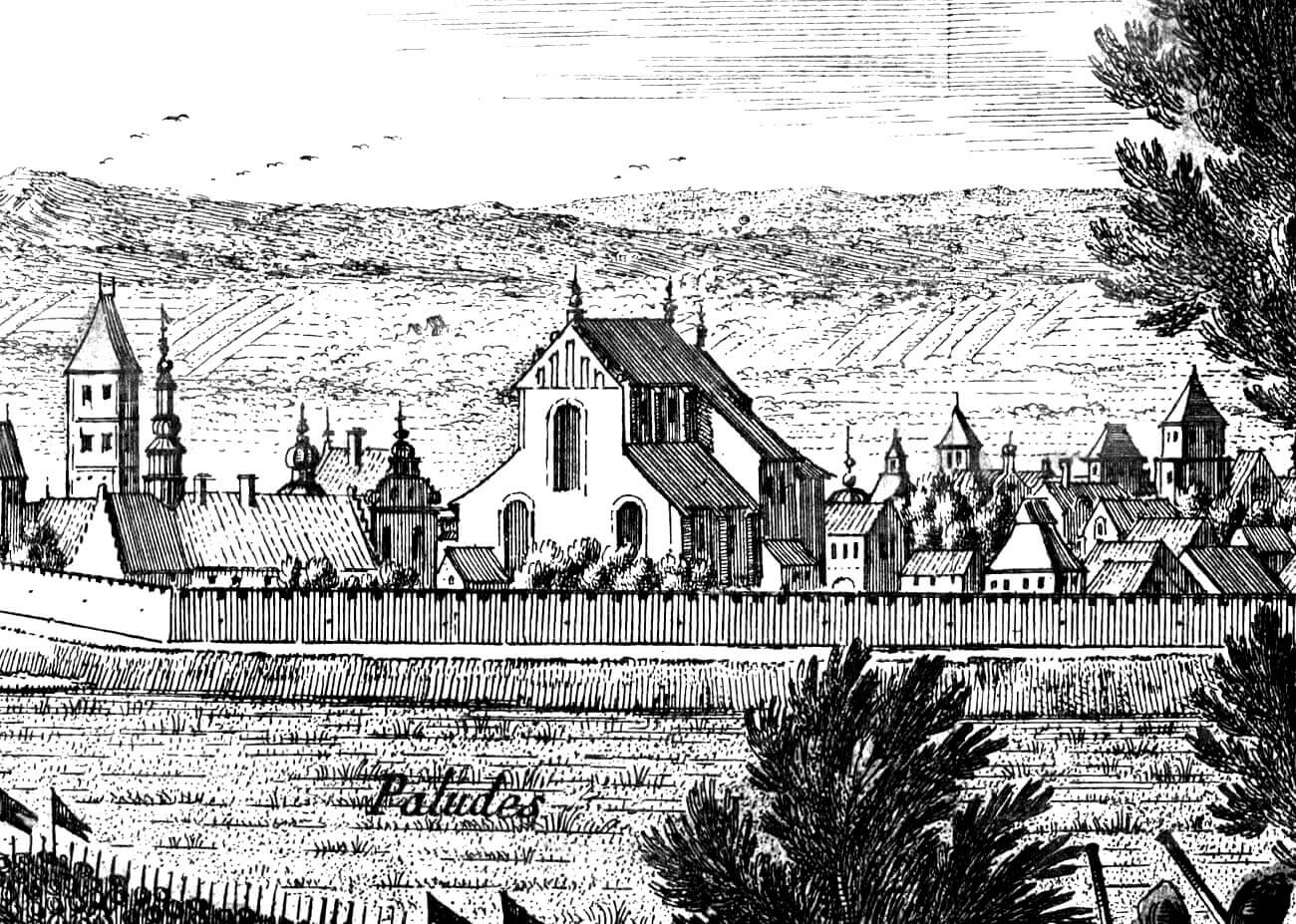

The late-medieval friary, after the town’s translocation from the fourteenth century, was situated in the northern part of Brześć, in the corner of the town marked by fortifications and the river Zgłowiączka flowing to the west. It was located on the opposite side of the parish church, located in the south-eastern corner of the town, which was characteristic of many medieval towns. This resulted from the division of influence zones between the churches, as well as from the defensive functions that brick buildings could perform in the event of sieges. The friary was located in close proximity to the town walls, which limited the buildings from the north and west. A four-sided plot of 0.5 hectares was probably also fenced from the south and east. Next to the church friary buildings and presumed economic buildings were situated, there was probably also a cemetery.

The church was a Gothic, brick, orientated building, situated in the south-eastern part of the friary area. It consisted of a central nave with two aisles, three-bays long, in the form of a basilica, i.e. with the central nave higher than the aisles and illuminated by its own windows. On the eastern side there was an elongated chancel with a straight ending, and on its northern side a late-medieval sacristy measuring 18 x 8 meters. The total length of the church was 35.2 meters. It did not have a tower, but only a small turret on the ridge of the roof covered with ceramic tiles. The external façades of the nave were clasped on the longer sides by three pairs of buttresses, added perpendicular to the axis of the church, and two diagonally buttresses supporting the western corners of the nave. The chancel was also reinforced with three pairs of buttresses. The main entrance to the church was on the south side, so from the town side.

The whole church was characterized by simplicity of forms, economy of details and modesty of decoration. The southern façade of the nave, serving as the main façade facing the town, had a more decorative form. There was a pointed, richly moulded portal from the second half of the 14th century, over which there was a circular blende, enclosed in a pointed gable, and on both sides of the latter, were formed ogival blendes in moulded framings. The elevations, including the buttresses, were probably also surrounded by a cornice. Although modest, the church was made by an experienced construction workshop, as evidenced by well-burnt tiles, window sill bricks and floor tiles. Probably the interiors were not vaulted, although a large number of buttresses would indicate that the vaults were originally planned. The interior of the sacristy was divided into four rooms, the last of which, from the east, was a brick passage, leading to the crypt under the chancel.

The monastery buildings were located on the northern side of the church. Most likely, it were of a wooden structure, possibly with a brick foundation, it is possible that only the priory house was fully bricked (at least one of the rooms had a cellar with a barel vault, discovered during archaeological research). The buildings, although modest, had to have all the rooms required by the rule, necessary for the daily functioning of the monks. In documents, a refectory (stuba), defined with the adjective “small” (parva), was recorded. So it was either small in size, or there was also a larger refectory in the friary. In addition, there had to be a dormitory, chapter house, infirmary, or a prison cell, as well as all kinds of utility rooms with pantries, sheds, latrines and a kitchen. In the latter, from the 15th century, there was probably a tiled stove.

Current state

Only the rebuilt monastery church has survived to modern times. Its present-day appearance is the result of early modern transformations, including the reconstruction of the interwar period, when the friary and church were kept in the Polish Baroque style, and its nave was shortened by 6 meters due to fire damages. During the reconstruction, the burned extreme bay of the nave was demolished, and the Gothic brick obtained in this way was reused to repair the most damaged northern wall. The only medieval element of the church now visible is the wall of the southern aisle with a Gothic, pointed-arch portal over which three blendes are placed.

bibliography:

Andrzejewska A., Kajzer L., Klasztor dominikanów w Brześciu Kujawskim [in:] Klasztor w mieście średniowiecznym i nowożytnym, red. M.Derwich, A.Pobóg-Lenartowicz, Wrocław-Opole 2000.

Grzybkowski A., Gotycka architektura murowana w Polsce, Warszawa 2016.

Optołowicz K., Klasztor dominikański w Brześciu Kujawskim w średniowieczu (XIII-XV w.), Toruń 2014.