History

The abbey called Nemus Sanctae Mariae (German: Marienwalde) was founded by Brandenburg margraves Otto IV, John IV and Conrad I from the older line of the Ascan dynasty. The motivation for the foundation was supposed to be compensation for war damage suffered by the mother monastery in Kołbacz at the hands of the Brandenburg margraves during the war with the Pomeranian princes. Abbey was recorded for the first time in 1280, in the acts of the general chapter, but it was not until 1286 that the margraves granted the Cistercians of Kołbacz 500 lans to establish a branch. The first buildings were erected in Bierzwnik between 1294 (arrival of the monks in Bierzwnik) and 1305 (foundation of the altar by Hasso von Wedel), when at least part of the church had to function. The first abbot was probably brother Werne, who led the expedition of monks from Kołbacz to Bierzwnik.

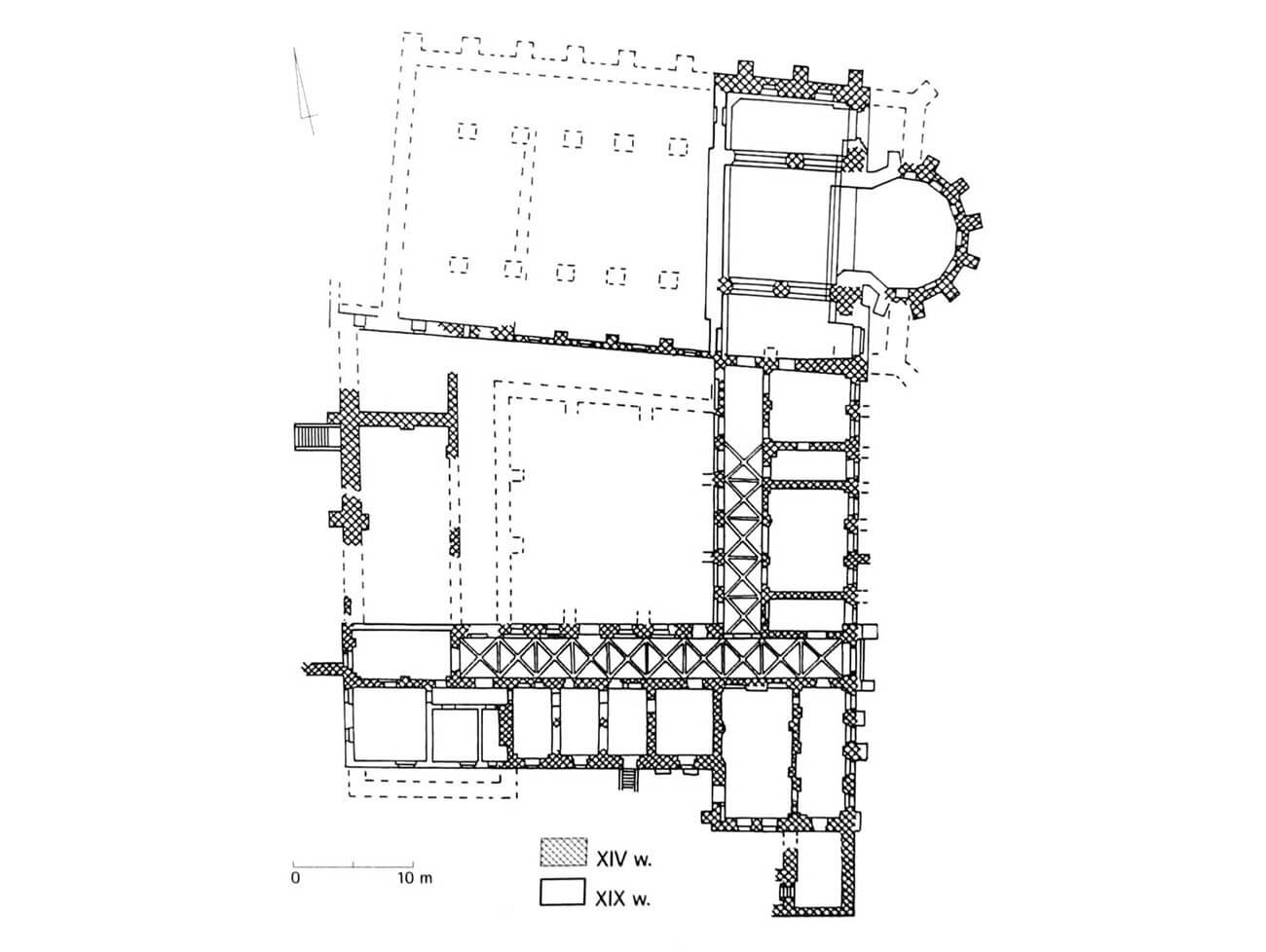

The construction of the abbey was carried out in three phases. In the first one, lasting from 1286 to around 1300, the church’s chancel, three bays of the nave and the sacristy, which was part of the eastern wing, were probably built. In the second phase, until around 1309, the western façade of the nave was completed, along with which work on the western wing of the claustrum was carried out in parallel. This was related to the stability of the church, situated on a partially levelled hilltop, for which the walls of the western wing were a partial support. In addition, in the second stage of work, the construction of the eastern wing was continued. In the last stage, the monastery complex was closed from the south, which took place around the years 1320-1326. The construction work was probably carried out by the construction workshop from the Cistercian abbey of Chorin, as indicated by similarities in many architectural details.

The situation of the abbey deteriorated after the Askan dynasty died out in 1320. The new ruler, Louis the Elder of the Wittelsbach dynasty, gradually pushed out the Pomeranian dukes and the allied Polish king from the New March. The retaliatory military expedition of Władysław Łokietek against Louis of Bavaria put an end in 1326 to the period of the best economic situation for the monastery. As a result of hostilities and the plague that accompanied it, many of the New March settlements were completely deserted. The abbey was robbed, the buildings burnt down, and the Cistercians for many years could not get out of the state of economic collapse. Moreover, in 1337, Louis questioned the privileges granted to the Cistercians and demanded from them pecuniary benefits in the amount of 400 marks. Only in 1341, due to the disastrous state of the economy, they were exempted from tax, but six years later the abbey was again destroyed by fire. A slow improvement of the situation took place only in the second half of the 14th century, thanks to the help of the monastery in Kołbacz and margraves of Brandenburg.

Another bad period in the history of the abbey took place in the first half of the 15th century, during the reign of the Teutonic Order in New March. The location of the monastery near the border with Poland meant that it was invaded several times. After the Battle of Grunwald, in 1411, a unit of Polish armed forces ventured into Dobiegniew and destroyed the abbey and its goods. Monastery villages were also ravaged in the years 1416, 1417, 1420-1422 and in 1433. To compensate for the losses in the 1430s and 40s, the Cistercians bought new estates, which were also enlarged in the second half of the 15th century. Around 1430, the situation was so tragic that the then abbot James intended to transfer the abbey to Prussia, which ultimately did not happen, and the situation stabilized after the end of the Thirteen Years’ War, when the New March passed under the rule of the Brandenburg Hohenzollerns.

In 1539, margrave John of Kostrzyn carried out the secularization of the abbey, and a complex of monastery buildings became part of the state domain. The abbot church lost its sacral function and was slowly devastated. The abbey also suffered during the military operations of the Thirty Years War, after which the local population drew building material from the post-Cistercian buildings. The devastation was stopped in the first half of the 18th century, when a summer residence of the Electors of Brandenburg was established in the preserved monastery buildings, and a glassworks was built in the church separated by a wall. Further losses to the abbey buildings were brought by a fire from the beginning of the 19th century, which completely destroyed the western part of the church and the chancel was seriously damaged. Renovation works were carried out in the 1850s, when the surviving buildings were adapted to the needs of the Protestant parish, but unfortunately many architectural details were removed from the historic rooms at that time. In 1945, a fire destroyed all the wooden elements, while the brick remains were secured after 1957.

Architecture

The abbey was situated on a slight elevation of the area, on the eastern shore of Lake Kuchta, near the Kaczynka stream flowing east of it, and on the northern side of the settlement. The foundation area was originally forested and swampy. The monastery consisted of a church, the claustrum buildings adjacent to the south with three wings surrounding with cloisters an irregular quadrilateral inner garth, and economic buildings located further to the south. North of the church there was a cemetery.

The church was a brick building erected in the monk bond, on a foundation made of granite stones. It had the form of a hall with central nave and two aisles, without a transept or tower. The nave was eight bays long and was ended with a polygonal apse, preceded by a rectangular choir bay, while at the end of the aisles there were rectangular chapels. The whole building was about 44 meters long. The width of the central nave was 8.2 meters and it was twice as wide as the aisles.

The external façades of the choir and apse (and probably also the aisles) were reinforced with slender buttresses, between which there were placed two-stage moulded windows, with the external profiles being pulled higher than the openings, creating a kind of niches into which were windows. The horizontal divisions of the façade were formed by the moulded plinth, the drip cornice at the height of the window sills and the under eaves cornice. The communication of the church was probably provided by three portals. One was placed on the axis in the western façade, the other connected the southern aisle with the cloister in the eastern part, and the third one in the western part.

In the interior of the church, octagonal pillars marked rectangular bays in the central nave and bays similar to a squares in the aisles. Moreover, the inter-nave arcades rested on wall half-pillars at the rood arch and at the western wall. The shafts of the vaults extended from the floor to the height of the base of the vault. The chancel was separated from the nave by the aforementioned massive, low-set chancel arch. The seven eastern parts of the chancel polygon were divided in the lower part with ogival niches deeply carved in the wall. High, pointed, two-light and quite narrow windows were set deep in the wall and were framed by modestly moulded jambs. Only one layer of bricks separated the niche heads from the windows zone. There was a crypt under the choir of the church. The partition of the rood screen, which divided the church into a part accessible to lay brothers and a part intended only for monks, was located behind the sixth bay of the nave. The interior of the church was probably covered with polychromes, and the windows were filled with colorful stained glass windows.

The monastery buildings consisted of three wings closing the inner courtyard and connected by cloisters with cross-rib vaults. Their almond-shaped ribs springin from the ceramic corbels decorated with floral, figurative and geometric motifs (e.g. an ox with a crown, images of devils, a stylized lily stalk, braid motifs). The cloisters opened onto the inner garth with ogival, originally non-glazed openings, separated from the outside by buttresses. All wings of the claustrum had a single-track layout. The eastern and western ones had two aboveground storeys, while the southern ones had one. Under the southern fragment of the eastern wing and the southern wing, there was a cellar, connected to the spacious cellars of the western wing. All cellars were covered with barrel vaults.

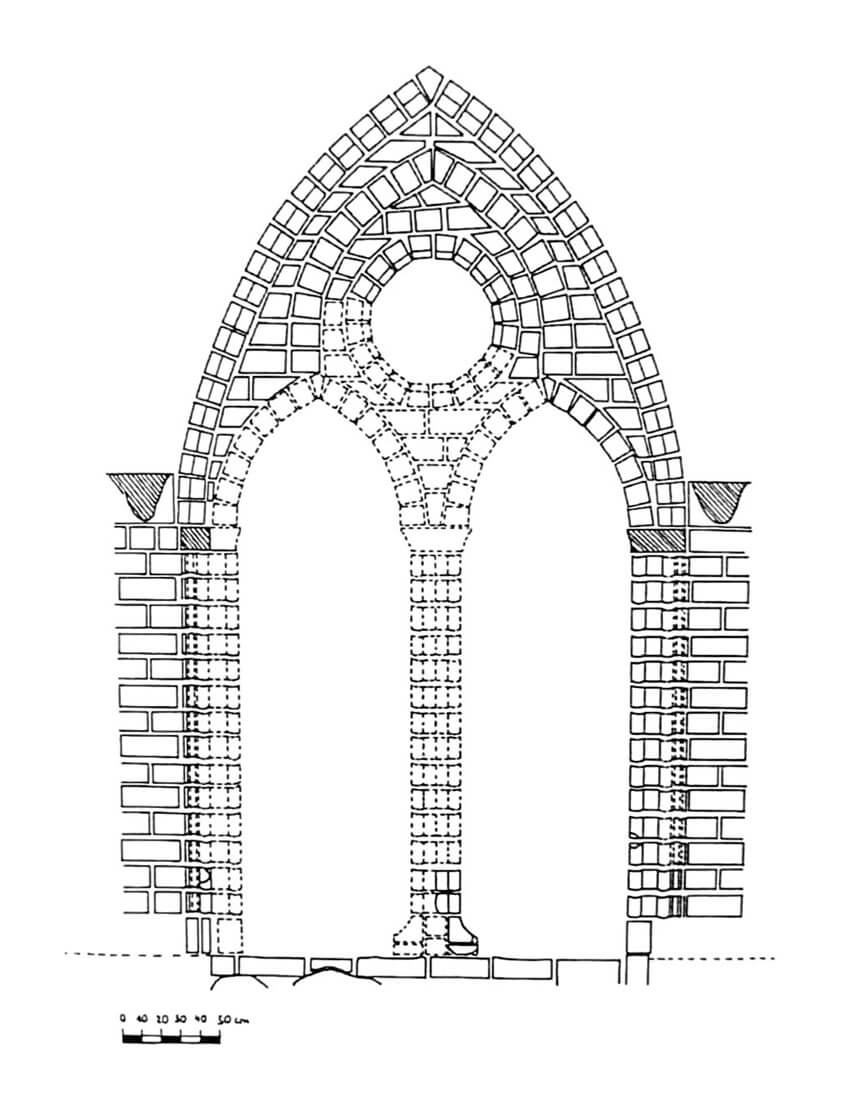

In the eastern wing, there was a vaulted sacristy on a square plan, adjacent to the church. Behind it was a small room covered with a barrel, probably a library or treasury. The next room was the chapter house with dimensions of 8 x 6.2 meters. It was a three-bay hall without pillars, covered with a rib vault with three-support bays in the extreme parts, equipped with a floor of ceramic tiles. A two-light portal with a finial in the form of an oculus framed with a pointed jamb led to it from the cloisters. Behind the chapter house there was a staircase to the first floor and a solitary confinement under the stairs. The last room of the eastern wing was the parlor and fraternity room. It were located parallel to each other, with the narrower hall having four bays and the wider three bays. The fraternity, as a place of work in winter periods, was heated by a hypocaustum stove located in the basement. Both rooms were originally covered with cross-rib vaults, springing from the wall corbels decorated with stylized lily motifs. The upper floor of the eastern wing was most likely occupied by the monks’ dormitory, initially in the form of one large room filled with straw mattresses.

The building of the west wing was about 35 meters long and 13 meters wide, of which 4 meters were for the cloister. Its northern wall was also a section of the southern wall of the church, in front of which the wing protruded by about 3.5 meters. The interior was divided into a basement, ground floor and first floor, above which there was an attic. Due to the terrain, the basement – cellarium measuring 15 x 8 meters was located only under the central part of the wing, with its northern wall acting as a retaining wall, reinforcing the foundations of the church located 6 meters away. The basement was covered with two barrel vaults supported by two pillars, placed 3.2 meters from the north and south walls and 3.2 meters from each other. Its floor was made of flat-lay bricks, including one with an ornament of circular rays. The walls had regularly arranged segmental niches. The entrance from the outside was probably from the west, i.e. from the lake side. In addition, there were internal stairs at the north wall. On the ground floor level, the southern part of the wing was occupied by a kitchen on a square plan with sides 7.5 meters, covered with a cross-rib vault supported by a central pillar. The kitchen was connected with the adjacent room measuring 15 x 8 meters, probably intended for the refectory of the lay brothers. The northern part of the ground floor could have been filled by a room in the form of a vestibule with the main entrance to the claustrum. The first floor of the building must have been intended for lay brother’s dormitory. In addition, there could have been a representative room in the wing, similar to the hall in Chorin Abbey. Intended for founders and patrons, it could have been connected to the gallery in the western part of the church.

The southern wing of the claustrum, in the form of a small, two-storey, rectangular building, was erected last, as a filling of the space between the western and eastern wings. Its southern elevation was not in line with any of the older wings, but was set back towards the cloister by about 2.5 metres, behind the gable wall of the western wing. In the southern wing, on the ground floor level, there was probably a monks’ refectory, located in the central part, separated by a smaller room from the kitchen (this small room may have originally been an extension of the western arm of the cloister and absorbed into the development after the southern wing was created). A ceramic chute from the kitchen ran by the southern and western wings, as well as a lead water pipe, connected to a well in the centre of the cloister’s garth.

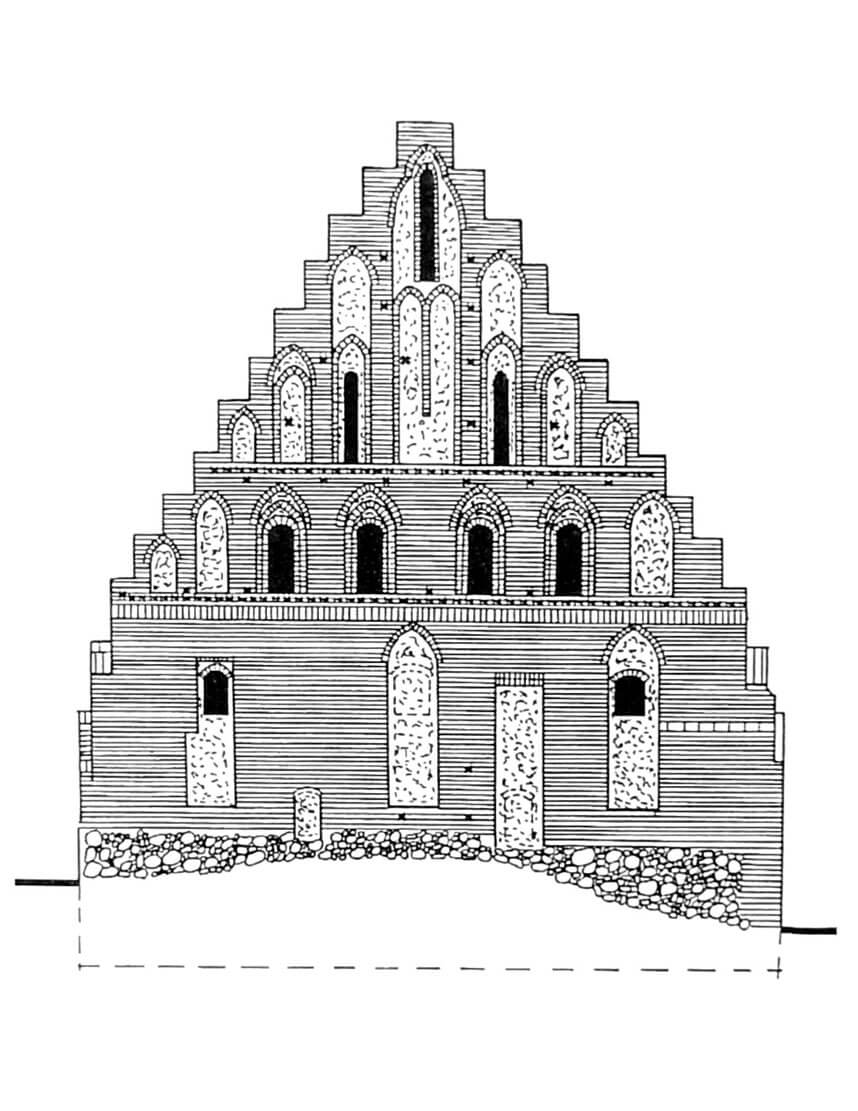

Economic buildings were located to the south of the monastery, including a brewery (or granary) from the fourteenth century, located about 20 meters from the lake shore. It was made of brick and stone on a rectangular plan, reinforced with buttresses in corners and covered with a gable roof based on triangular gable walls, decorated with pointed blendes, arranged in a pyramid and divided horizontally by friezes.

Current state

The relics of the medieval monastic complex preserved to this day, do not reflect the former splendor of the seat of the Cistercians of Bierzwnik. The eastern part, transformed in the 19th century, has survived from the former church, and it consists of a polygonal chancel and two bays of the former nave adjoining it. The part of the nave further to the west was almost completely destroyed. Only the outer wall of the southern aisle, preserved to a height of 3-4 meters, has survived to this day. Only the choir openings have retained the original shape of the windows in the church. The under-eaves cornice has not survived. The monastery buildings are: the ground floor of the eastern wing (with sacristy, chapter house and fraternity), southern wing (with transformed interior divisions) and parts of the basement of the west wing and elements of the western cloister, as well as the ruin of the monastery granary or brewery. Medieval vaults survived only in the cloisters. It is worth paying attention to the beautiful corbels, preserved despite the 19th-century devastation.

bibliography:

Jarzewicz J., Architektura średniowieczna Pomorza Zachodniego, Poznań 2019.

Jarzewicz J., Gotycka architektura Nowej Marchii, Poznań 2000.

Pilch J., Kowalski S., Leksykon zabytków Pomorza Zachodniego i ziemi lubuskiej, Warszawa 2012.

Płotkowiak M., Sandach I., Próba rekonstrukcji architektonicznej kościoła poklasztornego w Bierzwniku, “Zeszyty Bierzwnickie”, nr 4/2002.

Stolpiak B., Świercz T., Budynek konwersów dawnego opactwa cystersów w Bierzwniku, woj. zachodniopomorskie, w świetle źródeł archeologicznych [in:] Gemma Gemmarum, red. Różański A., Poznań 2017.

Wyrwa A.M., Opactwa cysterskie na Pomorzu, Warszawa 1999.