History

Soon after the founding of the city in 1201, a stone bishop’s court was erected, and a court of the Order of Livonian Brothers of the Sword situated opposite it, first recorded in 1209. After a dozen or so years, the bishop of Riga gave his residence to the Dominicans, and he moved to a new court located closer to the cathedral. In 1274, the German king Rudolf I Habsburg granted the Teutonic Order a privilege guaranteeing secular control over the city. This led to an exacerbation of the conflict between the archbishop and the order, which in 1297 took on a military character. The rebel townspeople conquered the order court and murdered its crew and, fearing the Teutonic reprisal, they formed a military alliance with pagan Lithuania. This did not help much, because in 1330, the Teutonic army besieged and captured Riga, and the defeated burghers were forced to accept the supremacy of the Order and pay for the construction of a new Teutonic commandry castle in the north-western part of the city. In the following years, this castle became the main seat of the land master of Livonia, while the old manor with the chapel of St. George was changed to a hospital and the church of Holy Spirit.

The conflict over control of the city smoldering further, among others, the trial at the papal court was conducted, in which the archbishops of Riga accused the Order of taking over the city. Finally, in 1366, the Livonian master renounced his rights over Riga, reserving only the right to own a castle. This situation changed in 1454, when the Teutonic Order came to an agreement with the archbishop of Riga, Sylwester, sharing power over the city with him. This treaty, called Salaspils, did not end the dispute. In 1484, the Riga townspeople made another attempt to regain political independence. They attacked and demolished the so-called the second order castle in Riga, which caused a war that lasted several years. As a result, after the battle of Ādaži in 1491, the Teutonic Order again defeated the rebellious city and forced the inhabitants to rebuilt the destroyed castle. Riga, who was exhausted by the war, was reluctant to fulfill the terms of the peaace agreement, so that the new, third castle was built only around 1515.

The average size of the new castle would indicate that from the very beginning it was not intended to be the seat of the highest authorities of the order, but only of a typical Teutonic commandry. The Land Master of Livonia, Wolter von Plettenber, resided in Wenden and probably rejected thoughts of full control over Riga. The new conciliatory attitude of the order, or the fear of the fortifications, protected the castle from attacks by the townspeople during the uprisings of the 1520s, carried out on the wave of the Reformation. The end of the building’s original function was brought only by the secularization of the entire Livonian branch of the Teutonic Knights. In 1562, the last Land Master of Livonia, Gotthard Kettler, paid tribute to the representative of the Polish king at the castle in Riga. The city and the castle came under Polish-Lithuanian rule, although Gotthard Kettler lived in the castle until 1578. From the fourth quarter of the 16th century, the castle was garrisoned by Polish military personel. It was the residence of the governor of the King of Poland, who provided rooms to Stefan Batory during his visits to the city.

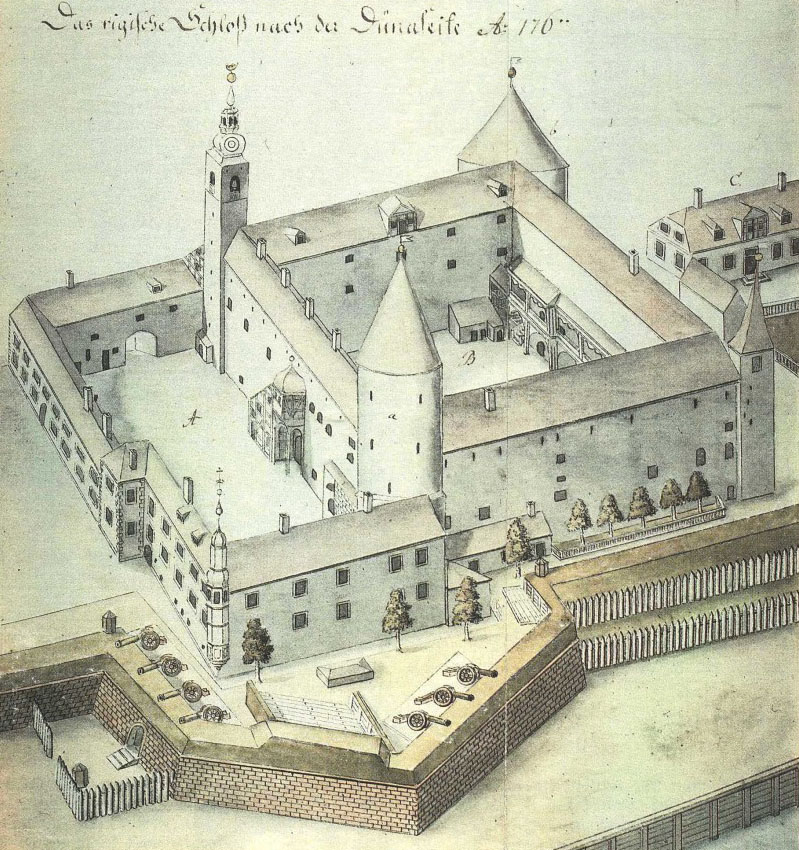

In 1621, Riga was captured by the Swedes for over a hundred years, and from 1710, the castle and the city were ruled by the Russians. During this period, the castle was thoroughly rebuilt and enlarged. First, the walls on the courtyard side were raised, the top floors of all four wings transformed and the castle was surrounded by bastion fortifications. Then, in 1682, an arsenal was added to the west and the outer bailey was adapted as the seat of the military command. In the years 1680-1720, the interior of the upper ward was transformed, and in 1758 an early modern cupola was added to the tower of the bailey. In addition, a new wing was added from the east. The Russians set up administrative offices and a court of the Livonia Governorate in the castle, which resulted in further transformations of the interior and the demolition of the Gothic vaults in the 1780s. In the 19th century, work was carried out on the reconstruction of the outer bailey and a new cloister. Another rebuilding took place in the 1930s to create the official residence of the Latvian president in the outer bailey. For the same reason, comprehensive renovation and reconstruction works were undertaken in 1994-1995, and at the same time, comprehensive archaeological research of the castle was carried out for the first time.

Architecture

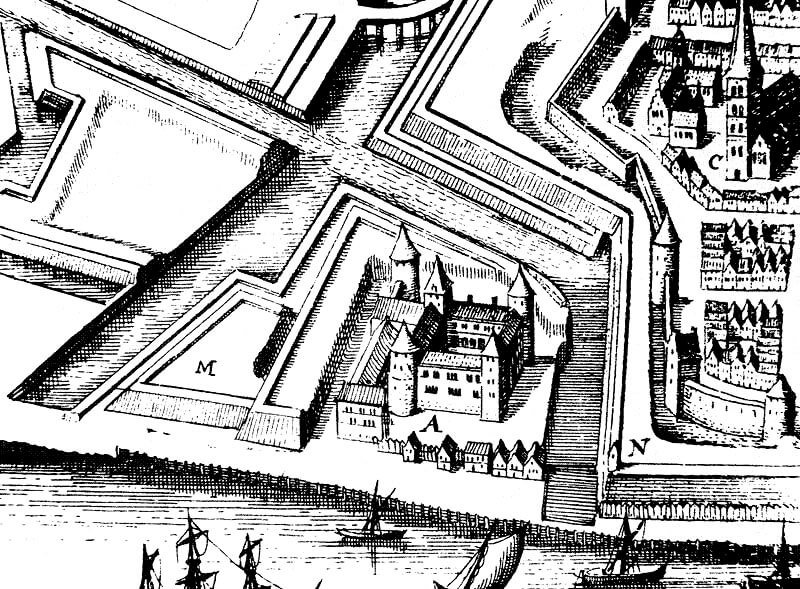

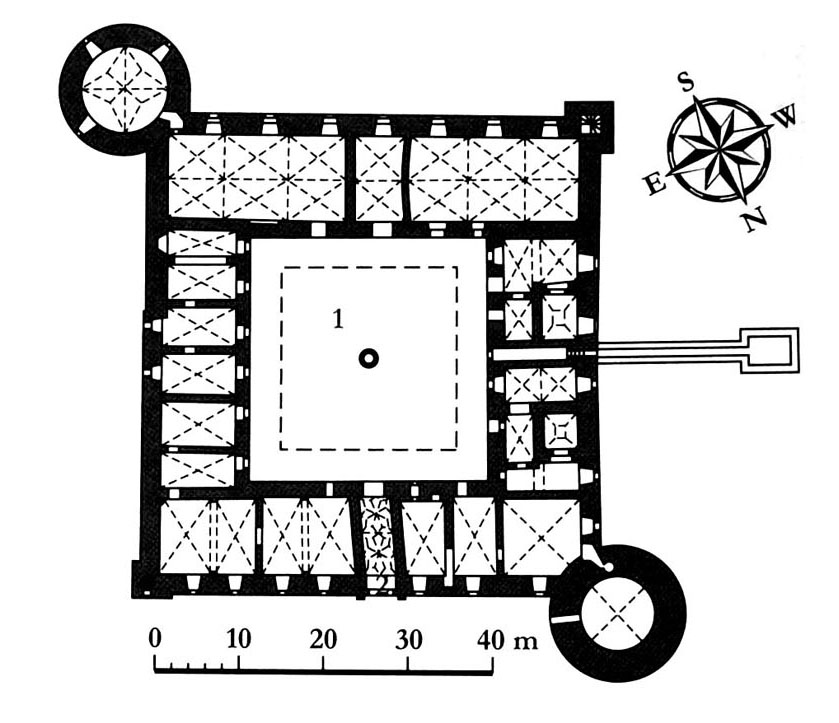

The north-western corner of the city, located right on the eastern bank of the Daugava River, was chosen for the construction of the so-called second and third castles of Riga. Initially, this area was probably located inside the perimeter of the city defensive walls, but with the construction of the castle, their course was shortened, so that the castle was an independent structure. The river protected the western side of the castle with a wide bed, while from the north and east it was protected by an irrigated moat, common to the city fortifications. On the southern side, an additional moat was dug, which separated Riga from the castle.

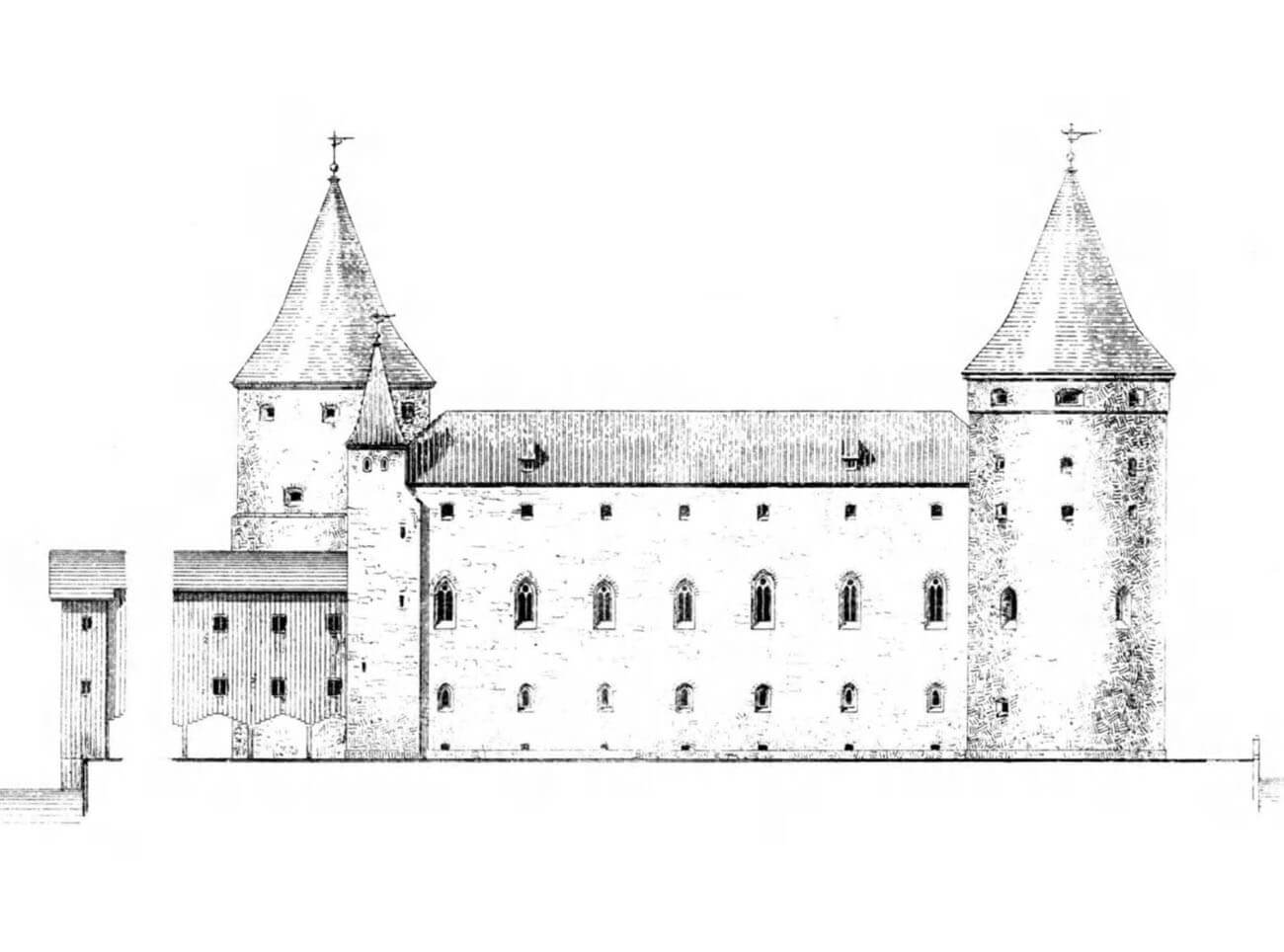

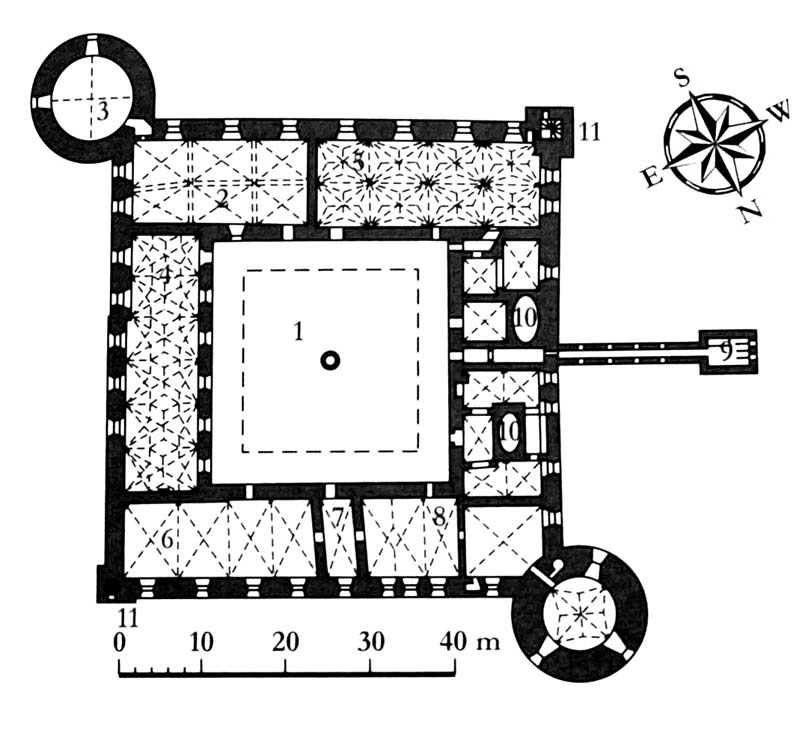

In the mid-14th century, the Teutonic castle in Riga was a typical commandry building, a four-wing structure on a square-like plan measuring 53 x 56 meters, with an internal courtyard of 28 x 29 meters, and with a dansker on the western side, extended towards the river. In the corners of the building there were slender four-sided towers. Initially it was believed that one of them, the northern one, could have had a more massive form, but currently the prevailing opinion is that the so-called second Riga castle had a four-sided tower of small size and slender shape in each corner. On the northern side the castle had a small outer bailey. Between 1364 and 1385, a four-sided tower was built on its premises, housing an entrance gate, which provided the castle with communication independent from the city.

The third Riga castle, built after the reconstruction at the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries, was similar in size to the earlier one, because it was built on the foundations and basement walls of the second castle. The third castle was distinguished primarily by defensive elements related to adapting the building to the use of firearms. Two of the corner towers retained their four-sided forms, but two were replaced with massive, cylindrical cannon towers: the north-west one called Holy Spirit Tower and the south-eastern one called Lead Tower. The outer zone of fortifications after the reconstruction was formed by a zwinger wall surrounding the entire upper ward, extended on the northern side to protect the small outer bailey. From the 16th century, there was a round cannon tower in its north-eastern corner. In the outer bailey there was also a two-story western wing from the early 16th century (perhaps built on the site of an older one) and a tower from the 14th century.

Inside the castle, on the first floor, the northern wing housed the commander’s chambers from the west and a dormitory. There may have been a chapter house in the eastern wing (although the functioning of this type of rooms in Teutonic castles is questioned in the light of the latest research) or another representative hall. The western wing housed a number of smaller rooms and a passage to the dansker facing the river. The most important southern wing consisted of a chapel in the eastern part and a refectory on the west side. There was also a sacristy on the same level, located in the south-eastern corner tower. The chapel was divided into two aisles and three bays by two octagonal pillars. It supported the cross vault, the ribs of which, roughly halfway up the walls, ran down onto overhanging, carved corbels. The adjacent refectory had a four-bay vault based on three pillars, originally probably of a similar shape, but it was vaulted again at the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries.

The rooms on the ground floor of the castle were traditionally intended for economic purposes, housing, among others, pantries, a kitchen, a bakery or a brewery, while the basements were mainly used for storing drinks and food. The north-western part did not have a basement, because during the second castle a well was built on the wall there, preserved in the third castle. In the central part of the ground floor of the northern wing there was a gate passage. The attic, located at the very top of all wings, served as a granary. According to the scheme of Teutonic castles, it could also be used for defensive purposes, thanks to the guard’s gallery running along the outer walls. Access to the rooms was provided by a stone, two-story cloister running around the castle courtyard. Originally, access to all rooms was almost exclusively through it. Each of the economic rooms also had easy access to the well located in the middle of the courtyard.

Current state

The so-called third Teutonic castle in Riga retained its basic shape from the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries, but unfortunately from the outside it almost completely lost its original stylistic features. Two cylindrical corner towers stand out, now plastered and with pierced modern windows, also smaller four-sided corner towers are visible. The eastern towers are no longer protruding in front of the walls, because the original layout was disturbed by the addition of a three-story building from the 18th century. In the area of the outer bailey, which was significantly transformed in the 18th and 19th centuries, the northern tower dates back to the second half of the 14th century, the walls of which have been preserved up to the level of the second floor.

Inside the castle a spatial structure from the early 16th century has been partially preserved, along with a chapel and a refectory representing of late Gothic design. Unfortunately, many other medieval rooms were thoroughly transformed during early modern adaptation works related to placement inside offices. They lost vaults and Gothic windows, the original communication was changed by the construction of a modern cloister in the courtyard, and the loopholes on the top floor were removed. At the basement level, walls dating back to the so-called the second Riga castle from the 14th century and all the vaults from the 16th century have survived. Only some partition walls are modern additions.

The castle currently serves as the presidential residence, but part of its interior housing the Latvian National History Museum is open to tourists. The building is an important part of the city’s architecture and silhouette, an important witness to the medieval history of Livonia. The results of the research conducted on it provided new insight into the development of the northern part of Riga in the mid-13th century, as well as the city walls and their towers, on the site of which the castle was built in the 14th century.

bibliography:

Alttoa K., Bergholde-Wolf A., Dirveiks I., Grosmane E., Herrmann C., Kadakas V., Ose I., Randla A., Mittelalterlichen Baukunst in Livland (Estland und Lettland). Die Architektur einer historischen Grenzregion im Nordosten Europas, Berlin 2017.

Borowski T, Miasta, zamki i klasztory, Inflanty, Warszawa 2010.

Caune A., Ose I., Die Befestigungen der Burgen und der Stadt Riga vom 13. bis 16. Jh., [w:] Castella Maris Baltici VII, red. F. Biermann, M. Müller, C. Herrmann. Greifswald, 2006.

Herrmann C., Burgen in Livland, Petersberg 2023.

Neumann W., Das mittelalterliche Riga. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der norddeutschen Baukunst, Berlin 1892.

Turnbull S., Crusader Castles Of The Teutonic Knights. The Stone Castles Of Latvia And Estonia 1185-1560, Oxford 2004.

Tuulse A., Die Burgen in Estland und Lettland, Dorpat 1942.