History

The construction of the brick cathedral of the Blessed Virgin Mary together with the chapter buildings (“monasterium et claustrum cum domibus necessaris”) began in 1211, when Bishop Albert laid the foundation stone during a solemn ceremony. Construction and fund management, the so-called “fabrica”, was entrusted to the Premonstratine monks, because in 1210, Bishop Albert, on his way back from Rome, visited the Westphalian monastery in Kappenberg, where he gave the chapter a rule modeled on the one that the hosts had. A certain Johannes, a member of the Premonstraten monastery in Scheda, closely related to Kappenberg, was elected provost of the newly organized Riga cathedral chapter. What may have been important is the fact that, unlike the Cistercians, the construction projects of the Premonstratensians were not limited by any rigid regulations or rules.

Construction work on the cathedral accelerated in 1215, after the first cathedral church, probably still wooden, located inside the Riga walls, burned down during a city fire. This prompted the canons of the cathedral chapter to move to the vicinity of the church under construction, which was being built closer to the river, in an area originally located outside the city fortifications. Already in 1226, Bishop William of Modena, the Pope’s legate, held a council in the cathedral, although further work could be temporarily suspended by the death of Bishop Albert and financial problems. In 1251, Bishop Nicholas, Albert’s successor, complained to Pope Innocent IV about the poor condition of the cathedral, and in 1254 Innocent IV called on the local congregation to make donations for construction works. Most likely by then the chancel and the transept had been completed and separated from the unfinished further part of the church by a temporary wall. The northern aisle was also partially built, narrower than the others and with semicircular windows, similar to those used in the transept.

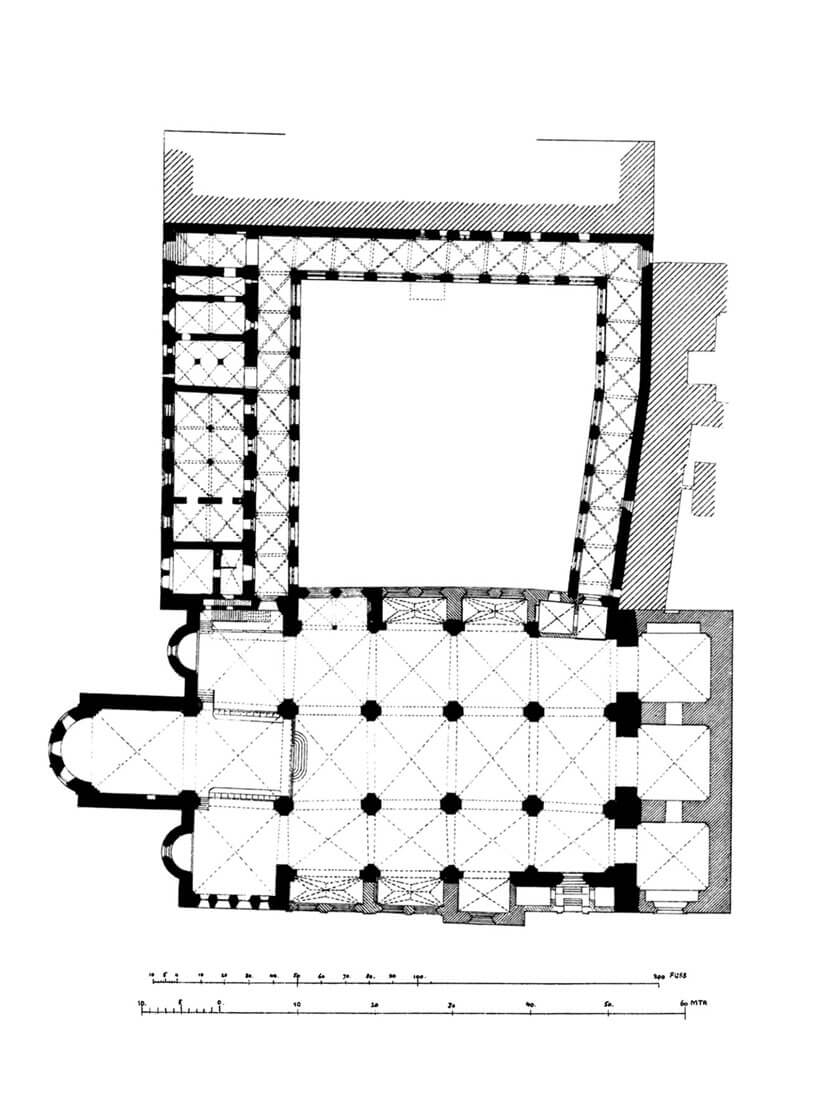

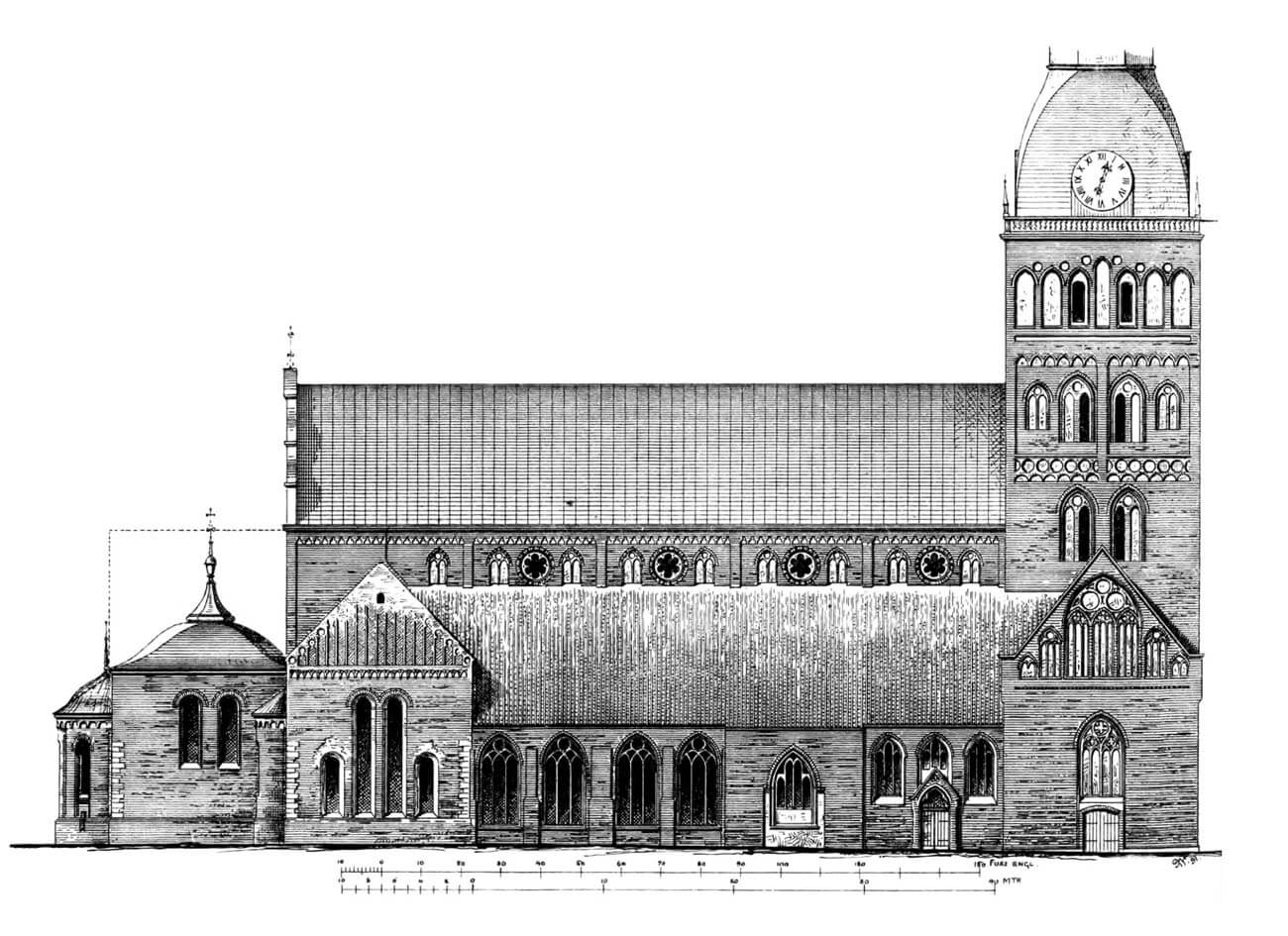

In the second half of the 13th century, the second stage of construction began, which resulted in the building of a hall nave with two aisles, connected via a cloister on the southern side with the chapter rooms. At the beginning of the 14th century, work on the tower probably began and the southern chapel of St. Elizabeth, while at the turn of the 14th and 15th centuries, work began on transforming the cathedral into a basilica by raising the walls of the central nave. This reconstruction lasted until about the middle of the 15th century, at which time the walls of the tower were also completed, an octagonal pyramidal spire was built and by the end of the century the last side chapels were added to the nave. Thus completed, the cathedral was the main episcopal church in Livonia until secularization in 1561. In the 15th century there were plans to rebuild also the chancel, but this idea was never carried out. Perhaps in connection with it, in 1431, Pope Eugene IV granted an indulgence for the church’s construction fund.

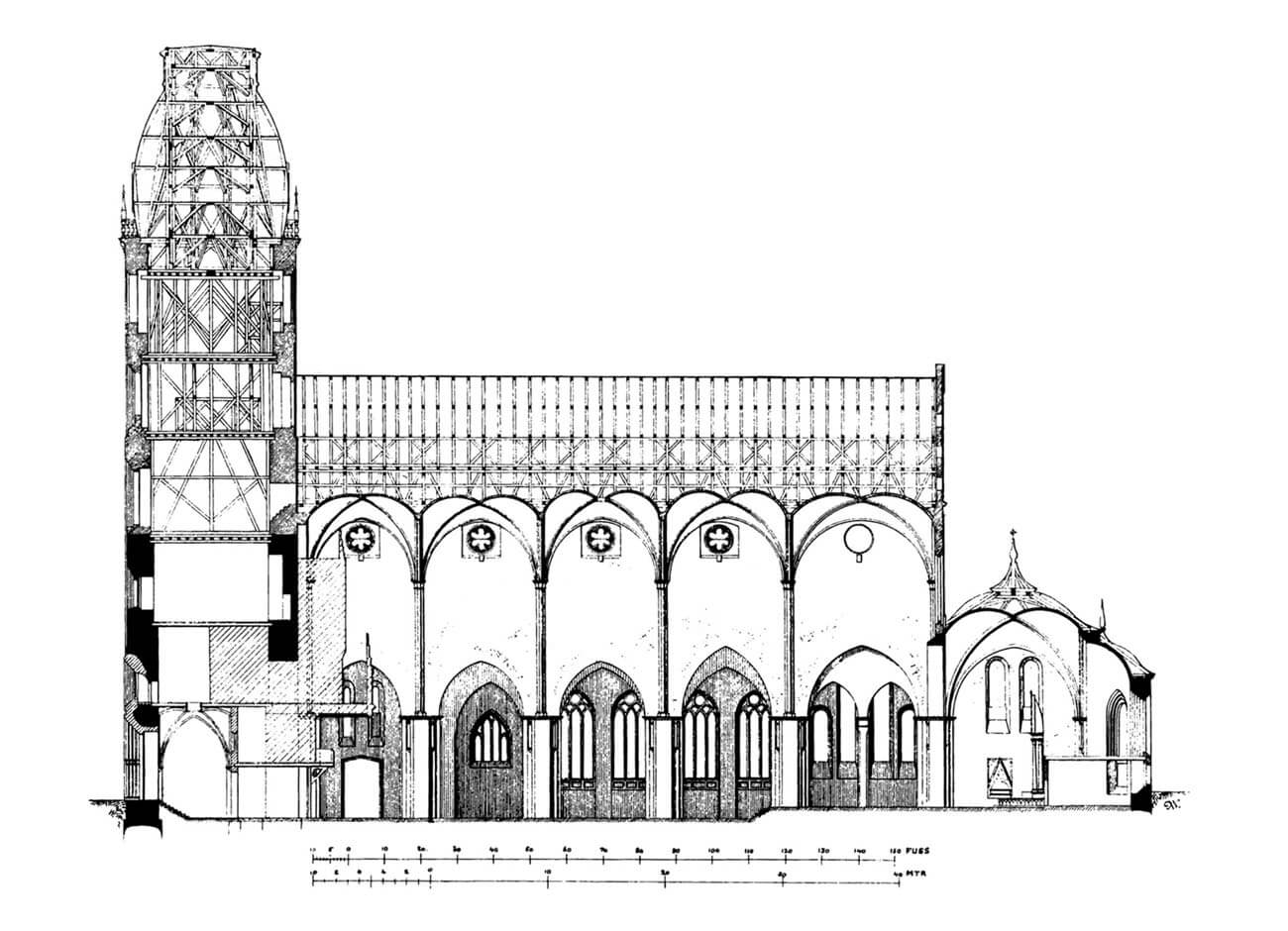

The cathedral retained its medieval appearance until 1547, when a great fire broke out in Riga. The Gothic church tower burned down, and it was not until 1595 that it received its early modern finial. In the 17th century, renovation and construction works were carried out twice on the tower, where cracks were noticed. During the siege of the city in 1710, the roof of the cathedral was seriously damaged. Later, during renovation works, the inclination of the covering of the aisles was changed, covering the round windows of the central nave. In 1727, the eastern gable was transformed, and in 1775, the Riga city council ordered the demolition of the tower’s dome and the construction of a new Baroque one. From 1881 to 1914, thorough reconstruction and renovation works took place in the church and cloisters. As a result of these activities, the cathedral and cloister gained their final appearance. Further renovation works were carried out from 1959 to 1962 and in the 1980s.

Architecture

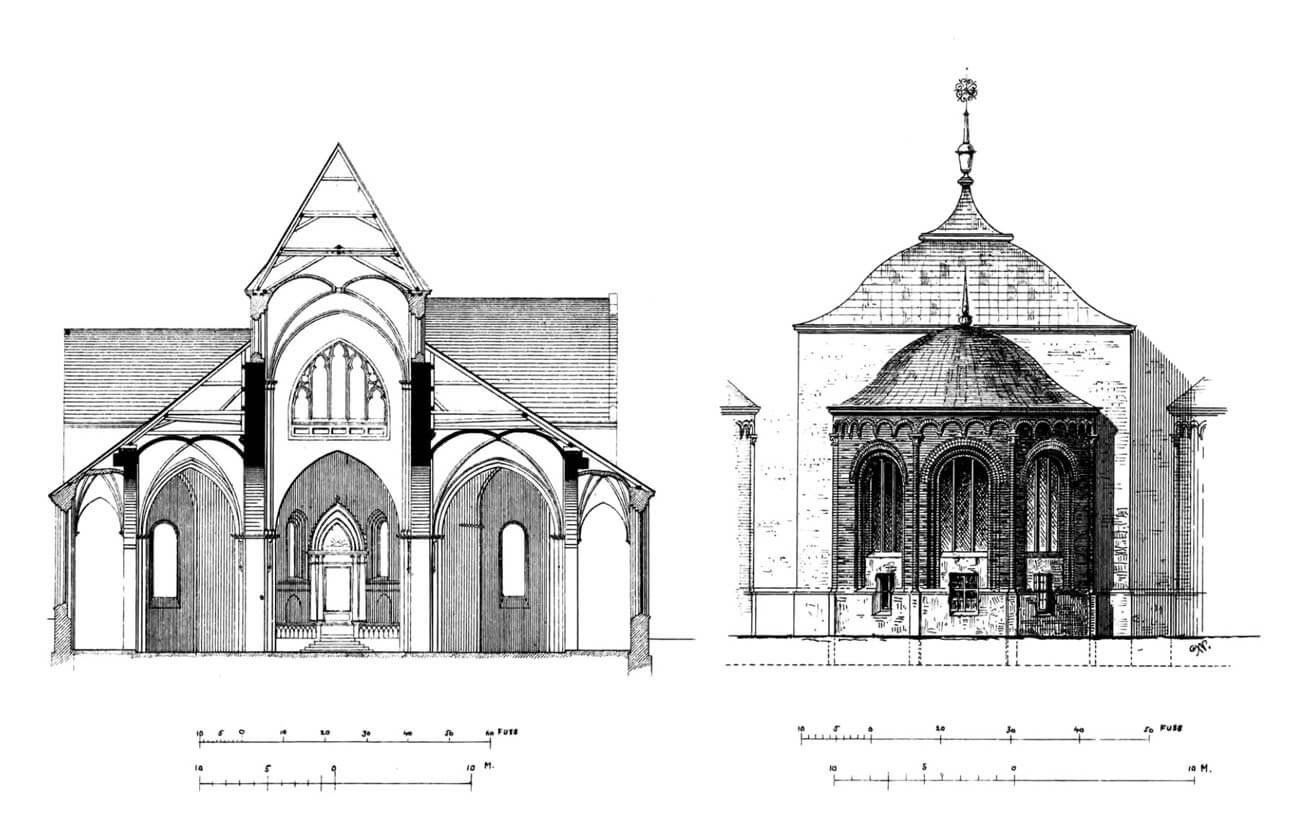

The cathedral was built of bricks in the monk bond, also using the opus spicatum technique (northern and eastern gables of the transept). Stone was used only in the earliest phase to build the foundations, plinth and external corners of the building, and then to make architectural details. Initially, the church had the form of a hall building with central nave and two aisles, but at the turn of the 14th and 15th centuries, when the walls of the central nave were raised, it took the form of a four-bay, 67.9-meter-long basilica. On the eastern side of the church there was a square-shaped chancel from the first half of the 13th century, ended with a semicircular apse, adjacent to a short, three-bay transept from the same period, measuring 38.3 x 10 meters, on the eastern side of which there were two shallow apses. The entire eastern part of the cathedral with its three-apse closure was Romanesque. The western part of the cathedral was crowned with a massive Gothic tower, flanked from the north and south with four-sided chapels, opened to the interior of the nave by large arcades. The cathedral’s structure was complemented by chapels founded from the 14th to the end of the 15th century, attached to the aisles on the north and south sides.

The older, eastern part of the cathedral was illuminated by windows of Romanesque forms: semicircular, relatively high, with moulded frames. In addition to the apses, chancel and transept, the northern aisle also initially had such an openings. In the remaining part of the nave, chapels and tower, pointed, moulded windows filled with stone tracery were used. Round rosette were placed on the axis of the western facade. Circular openings were also inserted in the central nave after the walls were raised, flanked by two-part pointed blendes. The decorations of the external facades included friezes, stone cornices under the windows of the oldest part of the church, small circular blendes on the walls of the chapels and the northern gable of the transept, and moulded cornices under the eaves of the roofs. The northern chapel next to the tower was richly treated, the top of which was decorated with pyramidal arranged blendes with brick tracery decoration, below which there was a frieze of bricks placed at an angle. Similar friezes were also used to divide the western façade of the cathedral and the individual floors of the tower, which with each higher floor gained an increasing number of blendes of various forms.

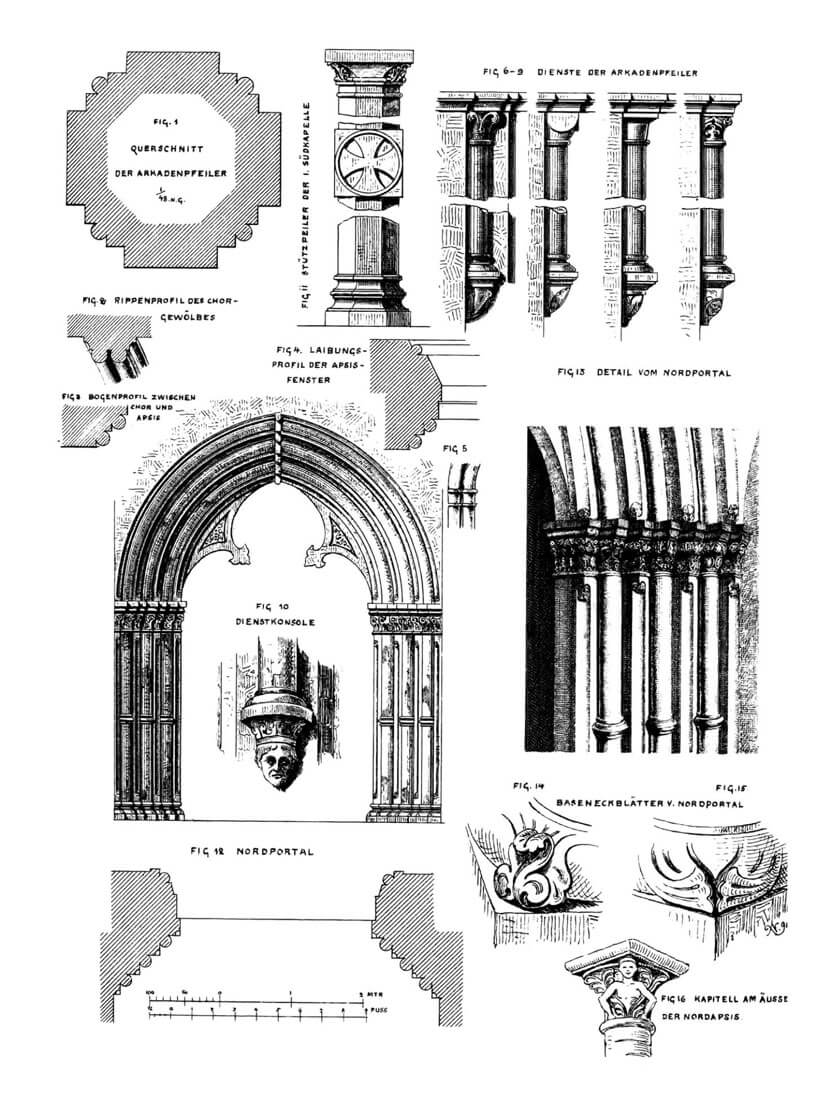

The entrance to the church from the outside was from the west, through the porch on the ground floor of the tower, but the most impressive entrance portal was located from the north, on the side facing the city. There was an exceptionally rich, pointed and stepped portal, with an opening filled in the tympanum zone with a trefoil, bas-relief tracery with two fleurons. Shafts were embedded in the moulded steps of the archivolt of the portal, fastened with rings on the keystone axis. On the sides, in the steps, columns were placed with capitals of relief plant decorations, perhaps influenced by Gotlandic motifs. Halfway up, the columns were tied with rings, and at the bottom they were finished with bases mounted on common plinth. Additional portals connected the church transept with the sacristy and the eastern arm of the cloister, and the nave with the western arm of the cloister.

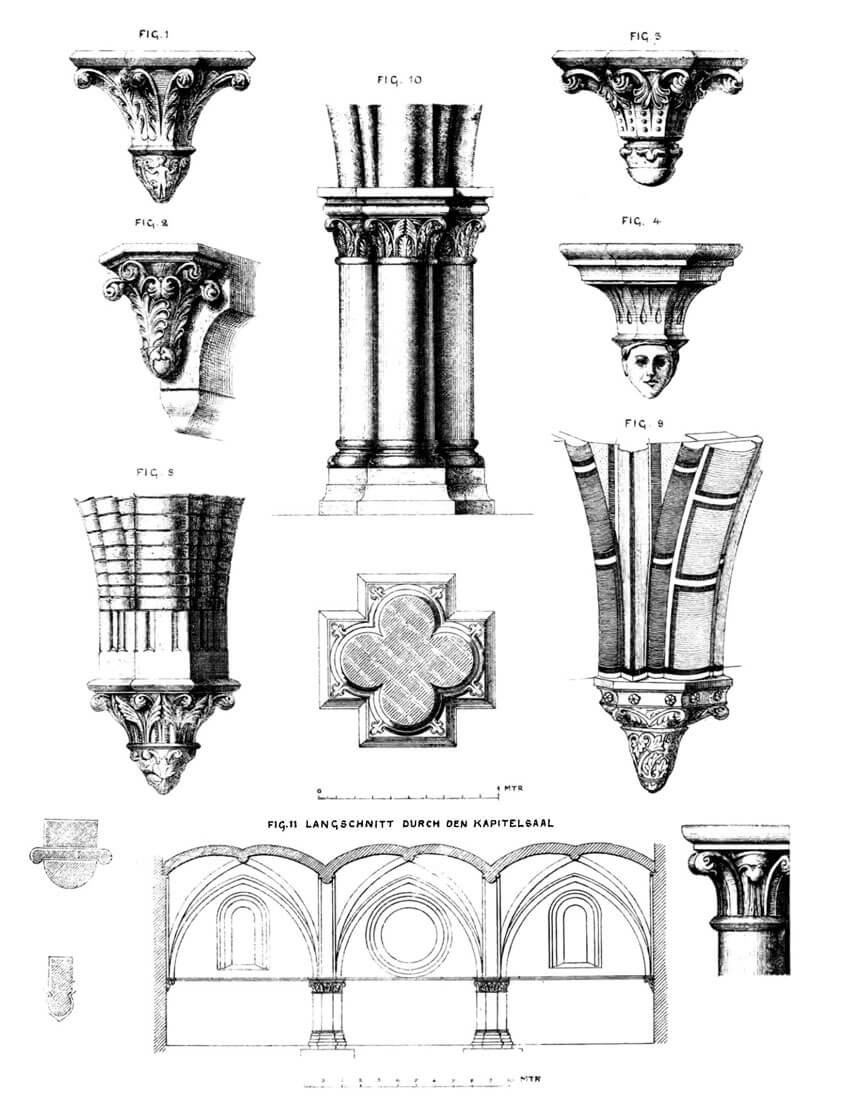

Inside the chancel, there was a single-bay cross-rib vault built, springin from the short corner shafts with capitals and corbels. A cross-rib vault with clusters of shafts was placed above the central bay of the transept, while in the side bays there were eight-part rib vaults. The nave was divided into aisles by cross-shaped pillars with unmoulded pointed arcades. The aisles were covered with cross-rib vaults lowered on short suspended wall-shafts. A similar solution was planned or even built for the central hall nave, where short shafts were left at the pillars even after the nave was raised to a basilica form. However, the cross-rib vault of the central nave from the turn of the 14th and 15th centuries was based on bundles of shafts ended in the capital zone of the pillars. Most of the side chapels were covered with stellar vaults and opened to the nave with single high arcades. The oldest southern chapel of St. Elizabeth from the beginning of the 14th century stood out, covered with a two-bay cross vault and facing the nave with two pointed arcades based on a slender octagonal pillar.

The interior of the cathedral was characterized by a simple, decoratively restrained design. Geometric shapes played a decisive role, creating clear spaces, characteristic of northern German brick architecture of the second quarter of the 13th century. The spacious bays with high vaults may have been created under the influence of Westphalian architecture. Similarly, the sacral architecture of the Westphalian churches in Lippstadt and Marienfeld could have influenced the shape of the slender, tapering ribs of the transept, or the style and motifs of the decoration of the capitals with double-row palmette wreaths.

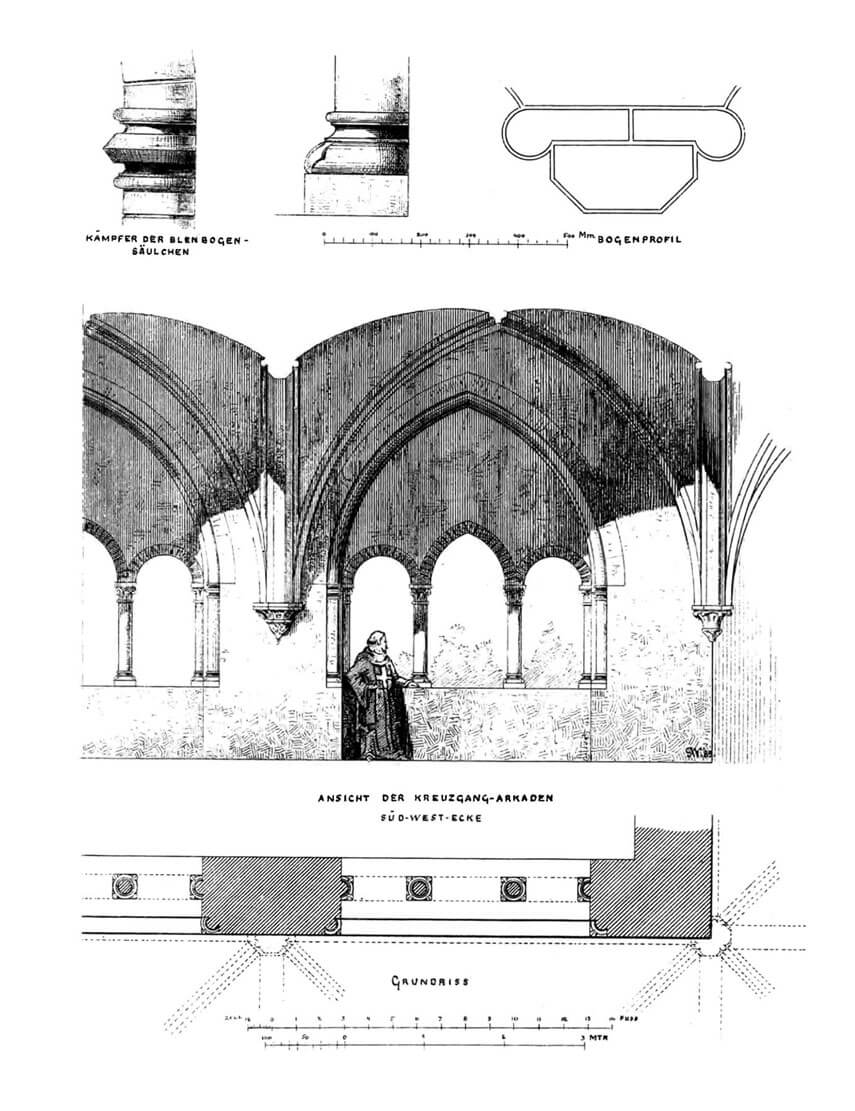

On the southern side of the cathedral, a garth was built on a square-like plan with dimensions of 38 x 40 meters, surrounded by three wings of vaulted early Gothic cloisters, which provided communication between the church and the wings of the chapter buildings. The passages of the cloister were 5.4 – 5.8 meters wide and 5.5 meters high. Unlike the church, it were characterized by a greater variety of sculptural motifs (palmettes, tendrils, ballflowers, as well as several figural scenes) and high plasticity of the ribs, arcade openings, consoles and capitals, especially in the eastern wing. The cross ribs of the cloister vault, along with wider arch bands, were lowered onto wall consoles decorated with plant motifs. The arcades around the garth were closed with pointed arches, on the side of the cloister with shafts in the archivolts, based on short columns flanking stone seats. Each three-light opening was divided by two central and two wall columns into two side openings with semicircular heads and a third central opening with a pointed arch archivolt. The whole was enclosed by one large, blind arcade on the courtyard side.

Inside the eastern wing, on the ground floor, there was a sacristy with dimensions of 8.9 x 6 meters from the north, and then a chapel of St. John measuring 8.9 x 4.5 meters, a two-aisle and three-bay chapter house measuring 13.2 x 8.9 meters, a staircase, a guard room and several smaller rooms. The eastern wing had a first floor since the second half of the 13th century. The southern wing probably housed a refectory, preceded by an avant-corps of lavaboo situated next to the cloister, inside which one could wash before a meal.

Current state

The Riga Cathedral is the largest medieval church and the oldest monumental religious building in the area of former Livonia, which influenced the further development of local architecture. It combines the features of Romanesque and early Gothic architecture, with minor modern transformations (tower dome, eastern gable, northern porch rebuilt in the 19th century, upper floors of the cloisters). One of its most valuable architectural elements are the 13th-century, early Gothic cloister, the only one preserved in the surrounding areas and one of the few in Central and Eastern Europe. Additionally, the rooms of the eastern wing have been preserved: the sacristy, the former chapel of St. John, a two-aisle chapter house, a staircase, a guard room and several smaller rooms, the original purpose of which is unclear. Currently, the cathedral serves the Latvian Evangelical Lutheran Church, it is also a concert venue and a facility open to tourists.

bibliography:

Alttoa K., Bergholde-Wolf A., Dirveiks I., Grosmane E., Herrmann C., Kadakas V., Ose I., Randla A., Mittelalterlichen Baukunst in Livland (Estland und Lettland). Die Architektur einer historischen Grenzregion im Nordosten Europas, Berlin 2017.

Bergholde-Wolf A., Der Rigaer Dom und seine Bauskulptur [w:] Livland im Mittelalter – Geschichte und Architektur, red. B.Aldenhoff, C.Herrmann, Petersberg 2022.

Neumann W., Das mittelalterliche Riga. Ein Beitrag zur Geschichte der norddeutschen Baukunst, Berlin 1892.