History

Originally, on the site of the castle there was a stronghold of the Livs. Thanks to the chronicler Henry the Latvian, it is known that its ruler was Vjaczko, dependent on Polotsk, who in 1207 agreed to become a vassal of Albert, bishop of Riga, and to give up part of his estates, including half of Koknese (“Kukenoys”) in exchange for protection and sending specialists in order to strengthen the fortifications of the stronghold. The masons arrived a year later and started digging stones in the moat (“ad edificationem castri lapides in fossato exciderent”), but the contract did not last long. As a result of the conflict, Vjaczko murdered the Germans, burned the fortifications and fled to Ruthenia. Albert took control of the destroyed stronghold and in 1209 began the construction the stone castle Kokenhusen (“castrum firmissimum edificavit”) in its place. Its basic form was ready around 1225, so it was one of the oldest stone buildings in Livonia.

A settlement grew up near the castle, which quickly turned into a town under Riga privilege and in the 13th century was fortified with stone defensive walls, first recorded in documents in 1277. Both town and castle became the main administrative center of the Archbishopric of Riga on the Daugava River, and the castle became one of its largest defensive structures. Initially, the bishop’s vassal had the right to two-thirds of the castle, while the Livonian Order held one-third of the castle. In 1213, however, the knights gave up their part in favor of territorial cessions in other areas. In 1269, Archbishop Albert transferred part of the lands under Kokenhusen Castle, which had previously been the property of Dietrich von Kokenhusen, to his widow Sophia and her second husband, Hans Tiesenhausen, a member of one of the most powerful and influential Livonian families.

In 1382, a document was issued to divide the inheritance between two heirs of the castle from the Erlaa and Berson branches of the Tiesenhausen family. It listed the vaulted living quarters upstairs, the old refectory (“datt olde rembter”), the slaughterhouse located outside, the mill, two vaulted cellars, the square where the wooden room stood, the warehouse at the attic, the gallery in front of the old refectory and the kitchen with a hearth. In addition, a prison tower and a stone house (“stenhusz”) on the outer bailey (“vhorwerk”) were recorded. In 1395, there was a record of an altar, which would indirectly indicate the existence of a chapel at the castle.

In 1397, the Archbishop of Riga took over Kokenhusen for himself, ending the period of the castle as the seat of vassals. Probably due to this fact, since the 15th century, the castle has been subjected to numerous modifications aimed at increasing the living standard and adapting it to the use of firearms. Among others, Archbishop Henning Scharfenberg, in office in the years 1424-1448, founded a tower called “langer Henning”. Despite this, in 1479 the castle was occupied by the Teutonic Knights, which imprisoned Archbishop Sylvester Stodewescher, who died shortly after his release in the same year. After the castle was regained by the church authorities, in 1556 a similar fate befell the last archbishop of Riga, Margrave William of Brandenburg. This time, the Polish king Sigismund Augustus rescued the hierarch from captivity.

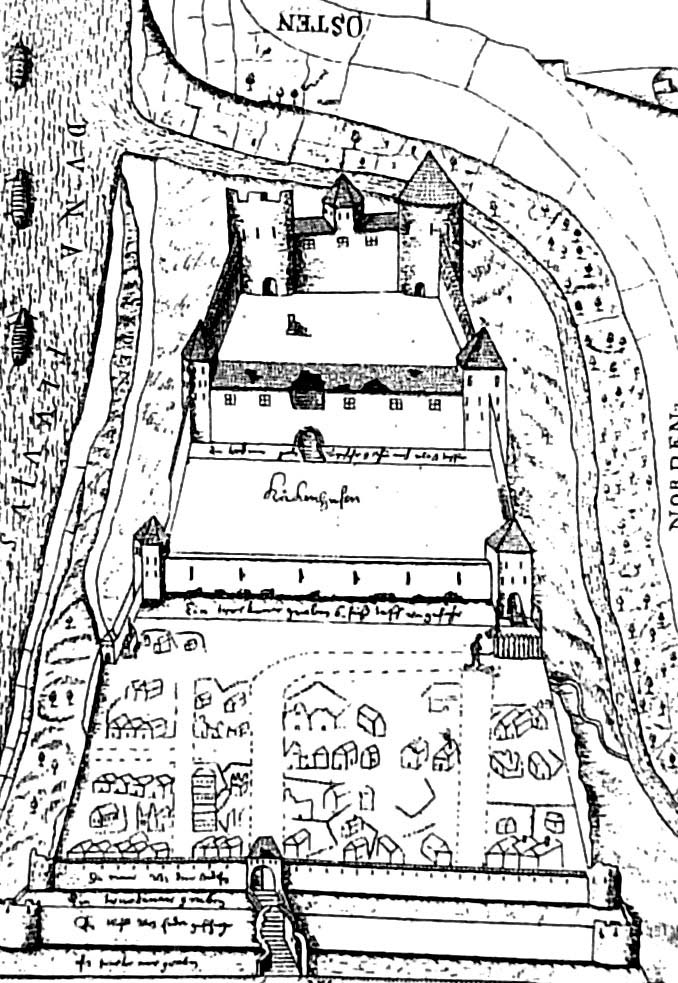

In 1562, the castle was devastated, like the entire archdiocese. After the fall of the archbishopric, in 1566 it was captured by Polish-Lithuanian troops, and the administration of the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth established a starosty in Kokenhusen. Due to the placement of officials in the castle, necessary repairs were carried out, preceded by surveys in 1590 and 1599. Repairs may also have been necessary after 1577, when during the Livonian War, the town and the castle were captured without a fight by the troops of Ivan the Terrible, who were quickly driven out by the Poles and Lithuanians.

During the Polish-Swedish wars, Kokenhusen was occupied by the Swedes twice, in 1601 and 1608, but Polish troops recaptured the fortress. Ultimately, the castle was separated from Poland in 1625 and remained under Swedish rule until the end of the century, although after the attack of 1656 it was occupied by the Russians until 1661. Despite the destruction, it still retained great military importance, increased by early modern fortifications. In 1700, the castle and the town were captured by the Saxon-Polish troops of Augustus II, but seeing no possibility of effective defense against the approaching Swedes, they left the stronghold, blowing up its main elements. Since then, the castle remained in ruins and the town was abandoned.

Architecture

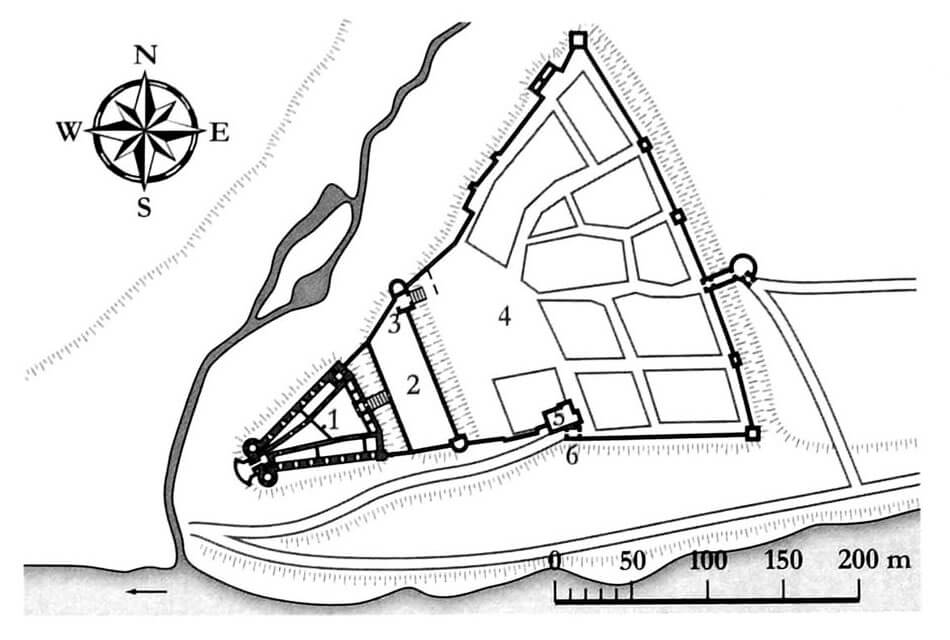

The basic plan of the castle, developed already in the 13th century, had the form of a two-part defensive structure located on a high hill. Its natural protection from the south was the Daugava River, and from the north and west, the smaller Perse River flowing into Daugava. The only convenient access to the castle could be from the east, so a transverse ditch was dug on that side. The main part of the castle occupied the western promontory of the hill, while on the widened eastern part of the hill there was an outer bailey, and further on, on a terrace between two rivers, a fortified town. The latter roughly repeated the shape of the castle, so it gradually expanded towards the east and was protected from the east by a moat.

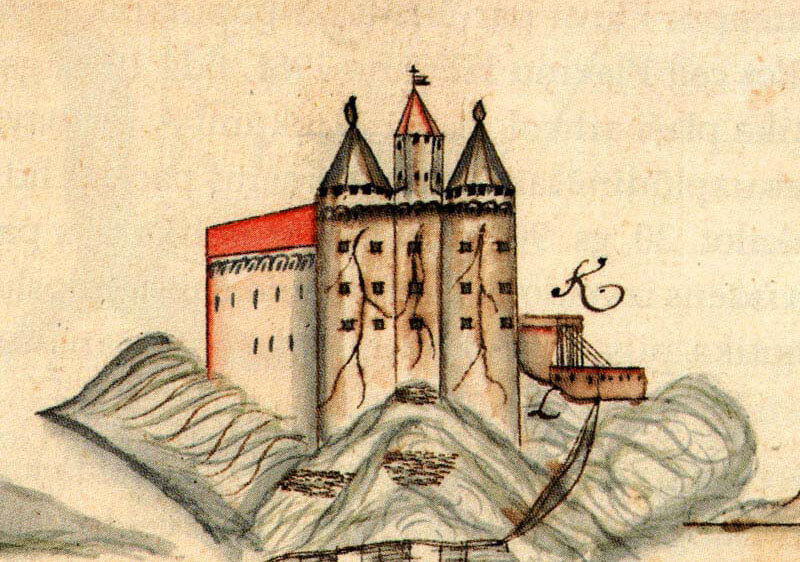

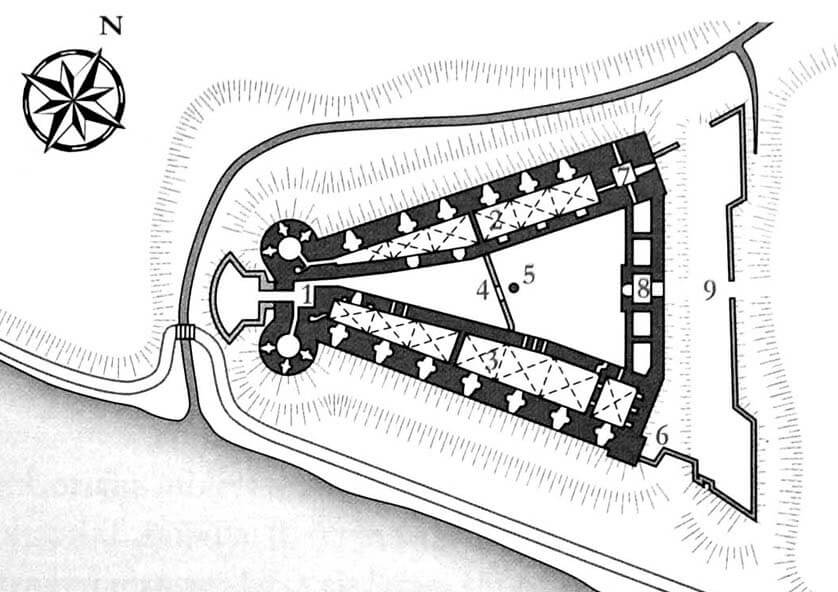

The plan of the upper ward did not refer to the Teutonic architecture of the commandry castle, but rather to the Western European model, and its roughly triangular plan, approximately 80 meters long and 60 meters wide, was largely influenced by the terrain. It had two wings separating a courtyard between them, expanding towards the east where the third wing was built. The perimeter walls were impressively thick, reaching up to 4 meters, while the walls of the two main residential wings on the courtyard side were about 2-2.5 meters thick. The western side of the upper ward was initially ended by one four-sided tower, from the first quarter of the 16th century placed between two cylindrical towers. Another four-sided tower was located in the north-east corner. Perhaps the southern wing also had a tower-like ending in the east. In addition, two corner towers had an outer bailey, connected to the town fortifications and to the upper ward.

The southern wing, approximately 64 meters long, had rooms in one line arrangement, expanding with the size of the courtyard. The western ones were less than 4 meters wide, while the eastern ones were about 8 meters wide. The interior was divided into a basement 2.9 meters high, a ground floor approximately 5.5 meters high and two upper floors. The northern wing had a similar form and arrangement of rooms. Its basement and ground floors were vaulted, just like in the southern wing. The eastern wing, compared to the previous ones, was both narrower and lower. It had at most one floor above the ground floor.

The castle’s economic and auxiliary rooms, like in the other defensive and residential buildings of that period, were located in Kokenhusen on the ground floor, while the representative rooms were probably on the first floor. There was probably a refectory in the northern wing and a chapel closer to the western tower. The ground floor in the northern wing was occupied by a brewery, bakery and kitchen, while in the southern wing there was a horse-powered mill. The slightly smaller eastern building probably housed guard rooms and utility chambers.

Current state

Nowadays the castle is a ruin, unfortunately without its main elements, which were its western towers and the north-eastern tower. The outer wall of the southern wing, most of its wall from the courtyard side and one of the partition walls have survived. The northern wing has survived only in the middle section of the outer wall, with one transverse wall and a very short section of the wall facing the courtyard. The contemporary surroundings of the castle, although picturesque, are completely ahistorical. Due to the construction of a dam on the Daugava River by the communist authorities, the water level rose significantly in 1966, as a result of which the hill disappeared and caused the castle to be at the same level as the river. The water weakened the foundations, which forced to reinforced them with a concrete in 2000-2002. Also a protection screen of about 1 meter height above the level of the river was built.

bibliography:

Alttoa K., Bergholde-Wolf A., Dirveiks I., Grosmane E., Herrmann C., Kadakas V., Ose I., Randla A., Mittelalterlichen Baukunst in Livland (Estland und Lettland). Die Architektur einer historischen Grenzregion im Nordosten Europas, Berlin 2017.

Borowski T., Miasta, zamki i klasztory. Inflanty, Warszawa 2010.

Herrmann C., Burgen in Livland, Petersberg 2023.

Tuulse A., Die Burgen in Estland und Lettland, Dorpat 1942.