History

The first, probably still wooden church, was built in the northern part of Tartu (German: Dorpat) in the first half of the 13th century, shortly after the conquest and Christianization of town by the Livonian Knights of the Sword. The oldest fragments of the brick church were built in the first quarter of the 14th century. In 1323 it was recorded for the first time, while the construction works and the rich decoration of the churdch were completed around the fourth quarter of the 14th century.

During the Reformation and the iconoclast revolt in 1524-1526, the church’s architecture survived without major losses, only the furnishing could be damaged or looted. The destruction was brought only by the started in 1558 Livonian War, fought between the Polish-Lithuanian commonwealth and Sweden, Denmark and Russia. After the end of the conflict, the church was repaired and was not subject to any major Renaissance or early Baroque transformations in the 17th century.

In 1704 Tartu, then part of Sweden, was captured by Russian troops, which led to great destruction of the town and the church four years later. The upper part of the church tower, the vaults in the central nave and the chancel were damaged, the furnishings were burned and the architectural decorations were damaged. It was not until 1737 that the church’s restoration began, during which a Baroque chapel was added on the south side. In the years 1820–1830, the interior of the church was thoroughly rebuilt in the classicist style. In 1944, the monument was destroyed as a result of a fire caused by violent fighting for Tartu between the Red Army and the Wehrmacht. The church remained in ruins for a long time, which led to the collapse of the northern wall of the central nave in 1952. Reconstruction began only in 1989 and was completed in 2005.

Architecture

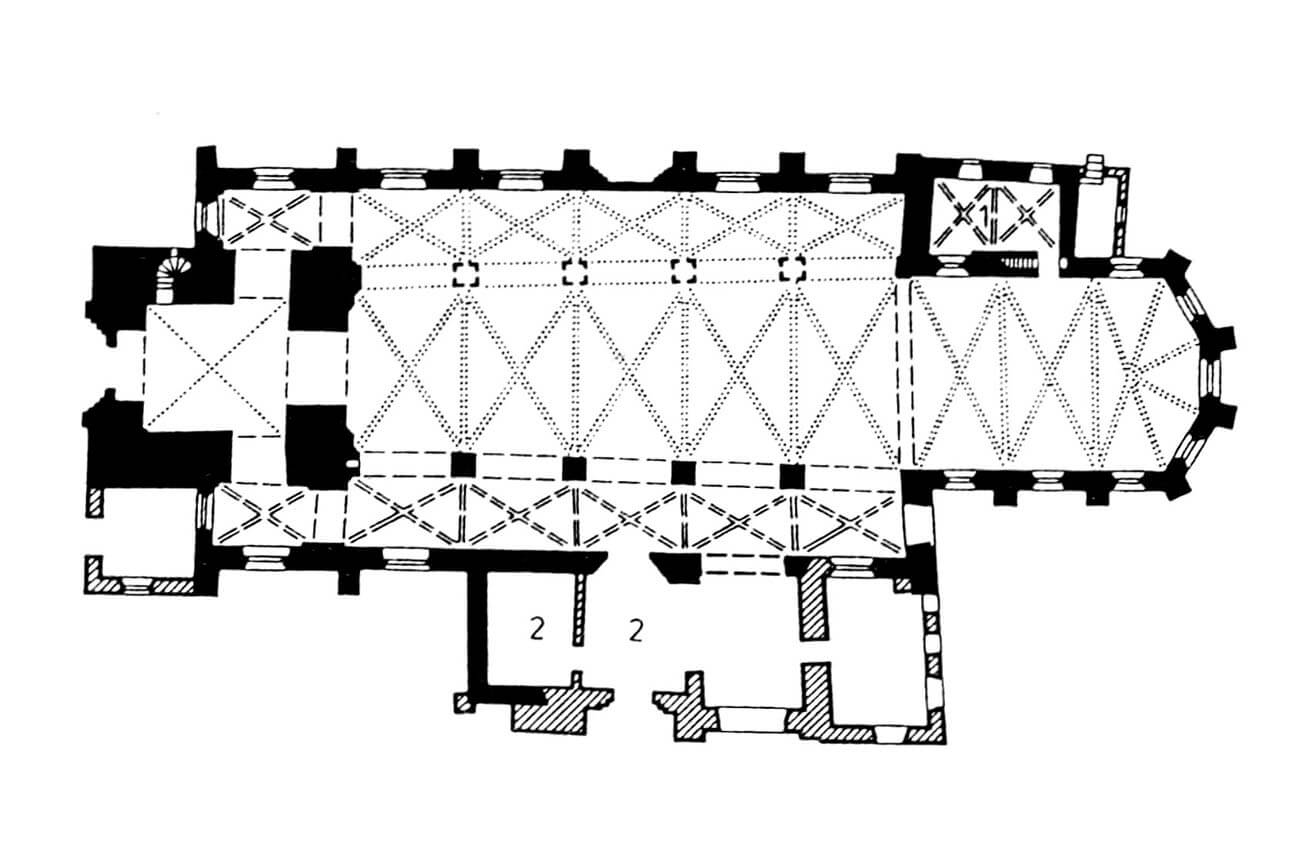

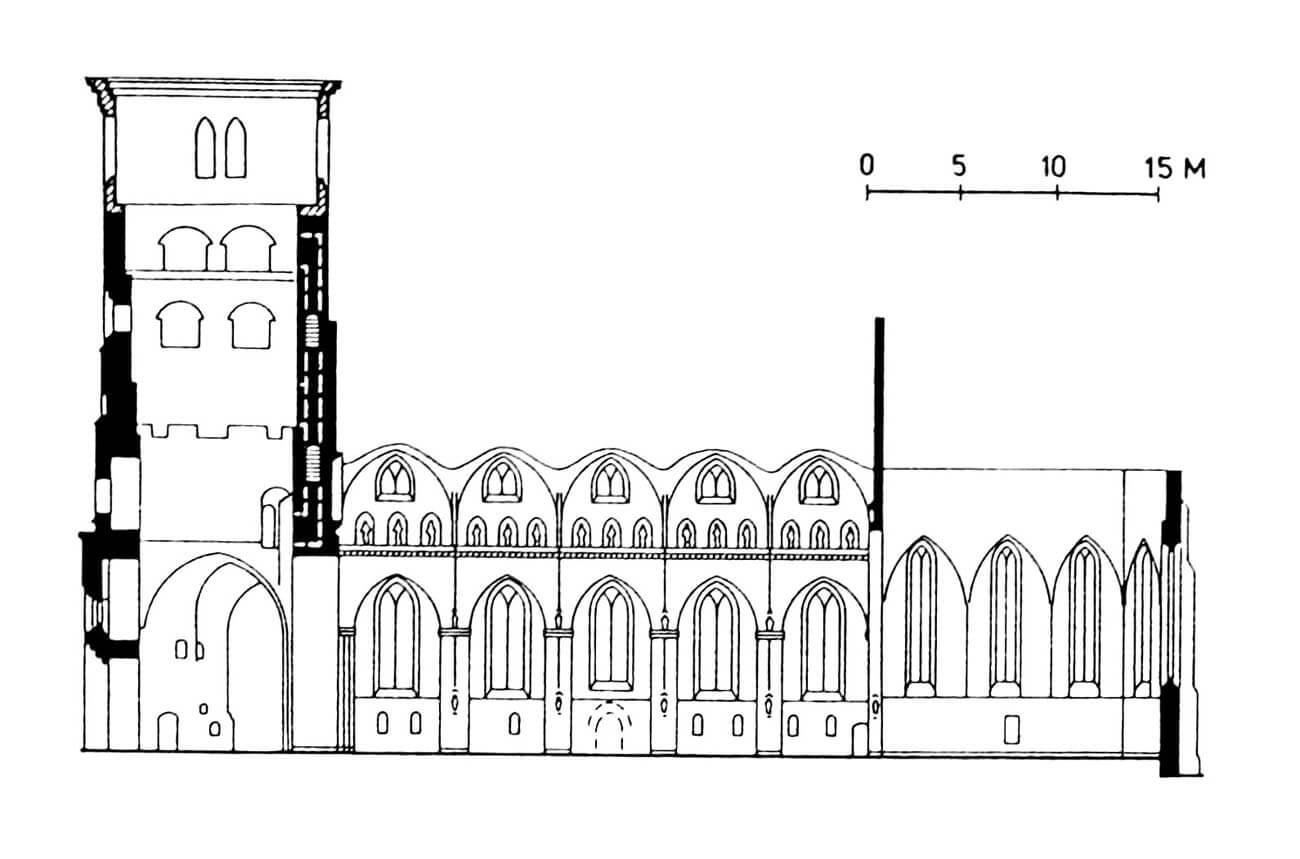

Church of St. John was built in the middle of the northern part of the charter town, as a five-bay basilica with a four-sided tower attached to the nave from the west, and an elongated chancel with a polygonal closure from the east. On the northern side of the chancel there was a two-bay sacristy. Another medieval annex was the two-bay chapel ended with a shallow three-sided apse, called Lübeck Chapel, located at the southern part of the nave. The tower was built on a square plan, as an extension of the central nave, and was flanked by two chapels on the extension of the side aisles.

The walls of the church were placed on a stone plinth, and the external facades were clasped with stepped buttresses, placed somewhat archaically at nave, perpendicular to the building’s axis, not at an angle. Moreover, the facades were decorated with friezes and blendes, numerous from the outside especially on the tower walls. Among the decorations, a unique solution was to place approximately two thousand separately modeled terracotta figures. They depicted saints and clergy, but they also featured images of fantastic animals and grotesque devils, and, above all, secular figures, including women, children, old people, knights and rulers. Each figure was hand-cut in wet clay, so that each image was different from the others. It is possible that the models for these sculptures were the faces of women and men who lived in Dorpat in the 14th century and died during the plague epidemics that were raging at that time. The figures were originally covered with polychrome, they had no attributes, but held ribbons in their hands with inscriptions, perhaps containing the names of the depicted people. In such a case, the creation of a very rich set of figures would have a commemorative meaning.

The main entrance to the church was the western portal on the ground floor of the tower, topped with a triangular gable with a small, pointed window and fifteen recesses, arranged in a pyramidal layout and with trefoil heads. Each niche housed a figure associated with the theme of the Last Judgment, which was related to the moralizing program of the main entrance to the church (Christ the judge, Mary and John the Baptist as kneeling intercessors and twelve apostles). The portal jamb acquired a stepped form with rich moulding. The second, slightly less lavish portal, without a gable, was set in the third bay from the east in the northern aisle. It had uniform orders and moulding, starting from the low, brick plinth to the top of the archivolt. Moreover, the walls of the church were divided by pointed windows with stepped frames, high in the chancel and aisles, low in the central nave.

Inside the nave, the division into aisles was provided by high, four-sided pillars with moulded corners and flat, relief capitals. Together with the buttresses, they formed a division into four-sided bays, in the aisles with longer sides parallel to the axis of the church, and in the central nave transverse to the axis. The spacing of the pillars was gradually increased towards the east, as a result of which the chancel arcade and the interior of the presbytery were exposed from the side of the main entrance portal and the under-tower arcade, but the form of the bays was distorted, especially in the northern aisle with a slightly trapezoidal plan of the bays.

In the central nave, the articulation of the walls was formed by pointed niches creating an illusory triforium, placed above the moulded inter-nave arcades and a quatrefoil frieze. The recesses were grouped three for each bay, and in each an additional rectangular niche was created, which originally contained carved figures. This rare pseudotriforium may have had its roots in Gothic architecture in England. The western wall above the high arcade leading to the tower was also distinguished in the central nave. There was a Maiestas Domini motif, shown in three pointed niches on the sides of the arcade and in a larger, trefoil-headed niche placed in the middle at the very top. The side aisles were designed more modestly, but even there the architecture was supplemented with niches with figures on the ground floor. All parts of the church were originally covered with cross-rib vaults.

Current state

Church of St. John is the best-preserved monument of brick Gothic architecture in Estonia. Its most valuable element are unique, separately modeled 14th-century terracotta figures. Supposedly, initially their number exceeded the sum of all other terracotta sculptures created in the Middle Ages in Western Europe, but unfortunately many of them were unfortunately destroyed during the reconstruction of the church, as a result of fires and wars. More than half of them have survived to this day. The originals are now in a nearby museum, and the church houses copies. Unfortunately, the vaults of the central nave and the chancel were also destroyed, and the medieval southern chapel was significantly transformed in early modern times.

bibliography:

Alttoa K., Tartu Jaani kirik ‒ kas katkumemoriaal?, “Õpetatud Eesti Seltsi Aastaraamat”, 1/2015.

Eesti arhitektuur 4, Tartumaa, Jõgevamaa, Valgamaa, Võrumaa, Põlvamaa, red. V.Raam, Tallinn 1999.