History

The oldest fortifications in Tartu (German: Dorpat) were built around the beginning of the 8th century, when a Finno-Ugric hillfort and an unfortified settlement at its foot were built. In 1030, the stronghold was captured by the Prince of Kiev, Yaroslav I the Wise, but no fighting was recorded at that time, and the ruler gave the seat a completely new name – Yuryev. Since Tartu was located near the Chud, in the years 1036-1061 it served as a border fortress of the Kiev state. It stopped playing this role in 1061, when the hillfort was burned down by local tribes. It was rebuilt later, because it was recorded in the chronicles in 1134 and 1191/1192, but on a slightly smaller area, and it did not have any major military importance at that time. According to the chronicle of Henry of Livonia, the stronghold was completely abandoned at the beginning of the 13th century. Archaeological sources indicate that it was used to a small extent, and the settlement at its foot disappeared.

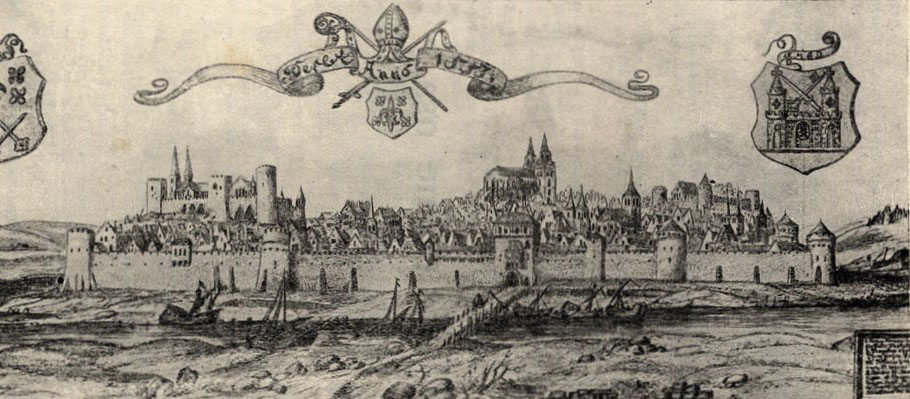

Between 1215 and 1223 Tartu was rebuilt, although in 1220 Henry did not recorded the hillfort when describing an expedition through the surrounding lands. The Livonian Brothers of the Sword contributed to the re-fortification of the castle hill by “strengthening it with hard work and great expense, and arming it with weapons and crossbows.” For a short period in 1223-1224, hillfort was in the possession of local insurgents and the Rus Prince Vyachko, who was helping the Aesti. In 1224, Tartu (“castrum Tharbatense”) was captured by the German crusaders, who then began to organize a Catholic diocese under the leadership of Bishop Hermann. The construction of the castle had to be started quickly, because in 1234 it was first recorded in documents, and in 1262 it managed to defend against the invasion of the Novgorod troops of Dmitry Pereyaslavsky, the son of Alexander Nevsky. As the devastations after the invasion were cleared, the settlement at the foot of the castle was reorganized into a charter town, around which the construction of defensive walls began in the early 14th century. The Tartu town council then asked Lübeck to support the construction of fortifications, but unfortunately the letter was not issued.

The fortifications of the castle and the town were one of the reasons why the Teutonic Order was unable to impose its supremacy on the episcopal principality in the Middle Ages. The invasion of Teutonic Master Wennemar von Brüggenei in 1396 was limited to the seizure of castles and the plundering of diocese lands, but Tartu itself remained unconquered. Town remained intact even during the Muscovite invasion of 1481. The castle and the city suffered damage only during the Livonian War of 1558 and the subsequent Polish-Swedish fights, when Tartu often was captured by both sides and the development of firearms revealed the anachronism of the old fortifications.

In 1625, after the withdrawal of Polish troops and capture of the town by the Swedes, three quarters of the Tartu was in ruin. As Tartu was much poorer than Riga, Tallinn or Narva, reconstruction was slow. Due to lack of funds the town’s medieval street network and its original defensive perimeter remaining unchanged until the end of the Swedish period. When Tartu was besieged by the Russians in 1656, the defense was still based on the dilapidated town walls, which were in such poor condition that in some places it was not even possible to post a guard on them. For this reason, as well as of the lack of hope for relief, the small garrison of only 220 people and the decline of morale, the Swedish garrison decided to capitulate without a fight.

In the second half of the 17th century, early modern bastion fortifications were built in front of the town walls, although not all planned works were completed. Like the outdated medieval fortifications, they failed to protect Tartu during the Great Northern War in the early 18th century. The devastated walls of the castle and town were completely demolished after peace was established in 1721, due to the desire to obtain building materials for the reconstruction of residential buildings (additionally destroyed by fires in 1763 and 1775).

Architecture

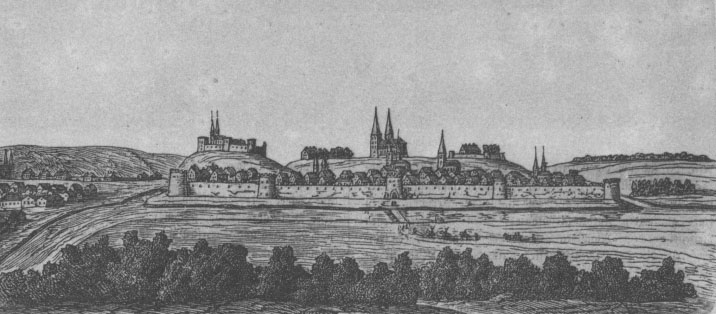

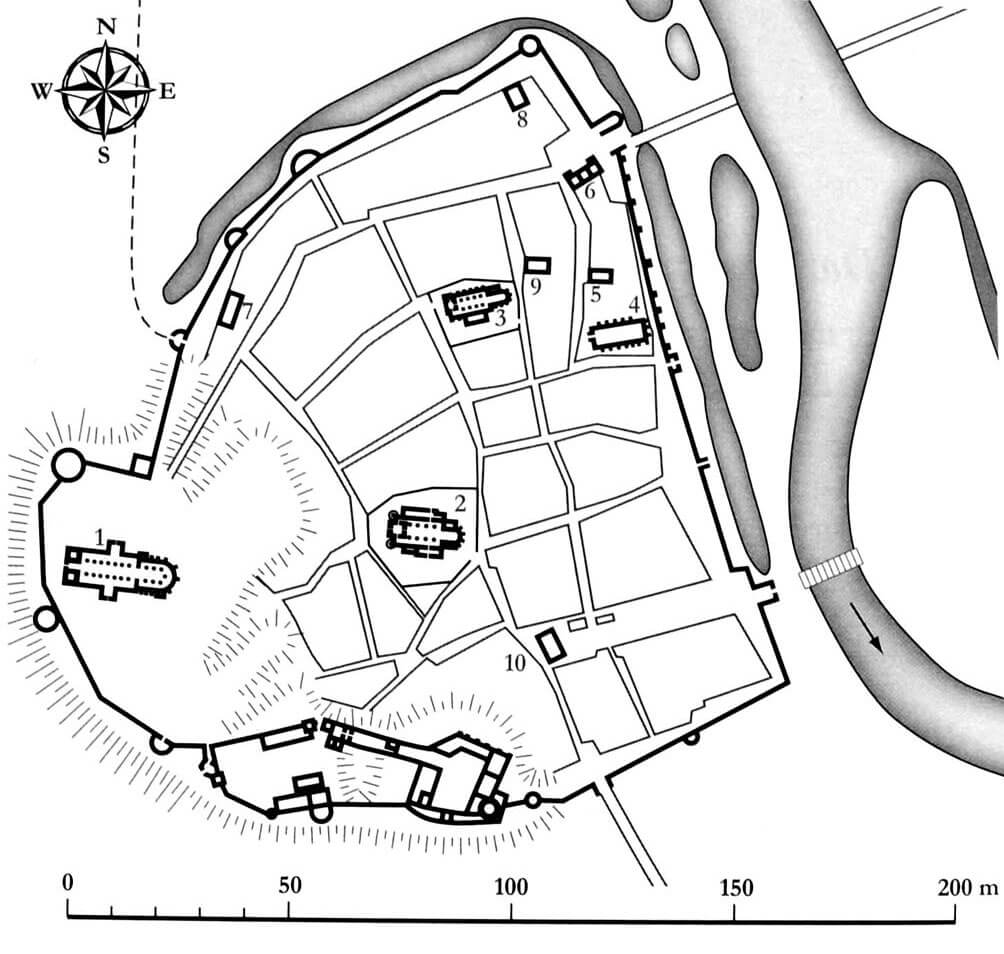

Tartu was founded in the wide valley of the Emajõgi River, flowing from the north-west to the south-east, on the eastern side of the town fortifications. On the northern side, the slopes of the river banks were steeper than in the southern part, where the current was probably slightly wider and more spread out. At the edge of the valley, in the southern and southwestern parts of the site, there was a large hill, selected for the construction of a cathedral church and a bishop’s castle. It was separated from the rest of the valley by a ditch. More or less in the central part of the town, far from the ring of fortifications, there were the parish churches of St. John and the Blessed Virgin Mary, while the market square with the town hall unusually occupied the south-eastern corner, where it opened onto one of the riverside gates. This riverside area was settled a little later than the center of the settlement, as it was originally swampy and had to be drained. The defensive wall was also built there at the latest, at the end of the construction process.

The town fortifications had an irregular shape in plan, adapted to the form of the terrain, in particular to the riverbed and hill slopes, which they climbed on the western side to surround the cathedral and connect with the castle in the south. At the end of the Middle Ages, the entire area occupied approximately 27.6 ha, but excluding the castle hill, it covered approximately 20.7 ha. The fortifications consisted of a single line of stone defensive wall with a total length of approximately 2,145 meters, preceded by a moat except for the sections on the hill. The wall was built of erratic stones, limestones, fragments and intact bricks, connected with irregularly poured lime mortar or just soil. The thickness of the wall varied in different areas: from 1.7 to 2 meters on the northern side, up to 2-2.4 meters on the eastern side and up to 2-2.9 meters on the southern sections. The height was about 9-9.5 meters. The wall was strengthened by a total of 18 towers, most of them horseshoe-shaped and semicircular in plan and cylindrical in the corners of the fortifications. The thickness of tower’s walls also varied greatly, ranging from 1.9 to 4.5 meters, which may have resulted from different construction periods, including the adaptation of the fortifications to the use of firearms.

The entrance to the town was to be through as many as 9 gates, most of them in tower-like form or with passages flanked by towers. On the north-west side, at the foot of the hill, there was Jacob’s Gate. At the junction of the outer bailey of the castle and the cathedral part of the hill, there was a Cathedral Gate, while on the eastern side of the castle, the entrance to the town from the south was provided by the St. Andrew Gate. The German Gate was facing the river, opened to the market square. Next was the Monk’s Gate at the Dominican friary, as well as the Russian Gate near the north-eastern corner. In addition, communication with the riverside was supported by smaller posterns.

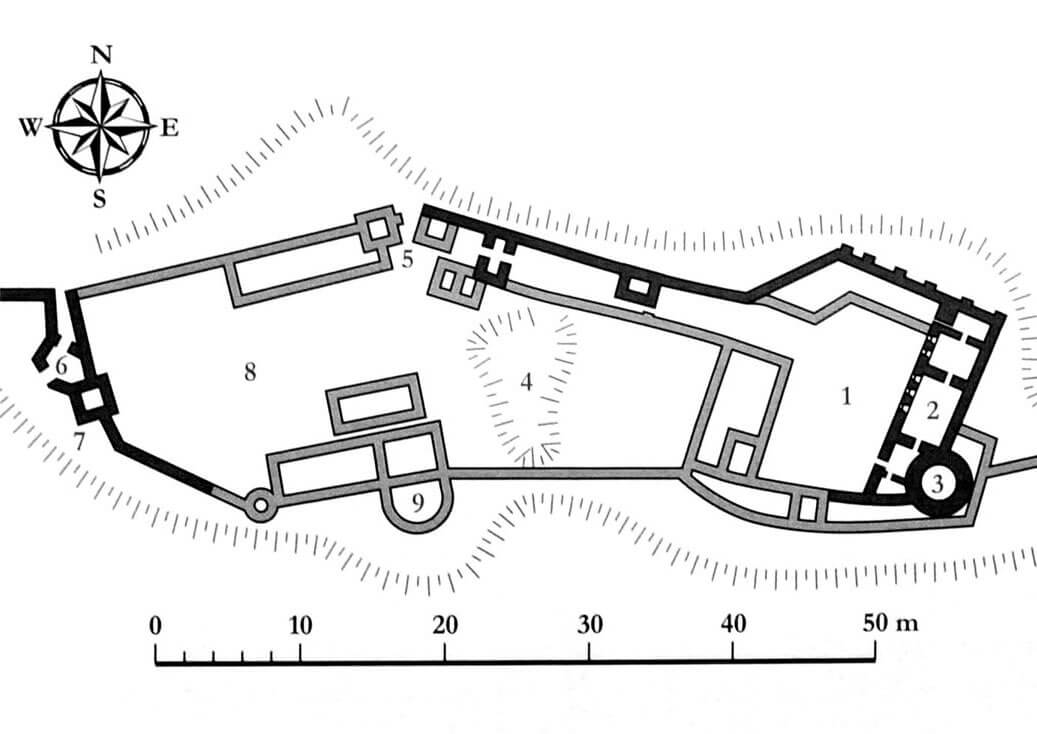

The castle was built on a hill above the town, on its southern side, probably in a mixed brick and stone technique. Its poorly recognized layout probably consisted of an upper ward and a fortified outer bailey located west of main part, separated by a ditch. The whole structure had an elongated shape with defensive walls placed close to the edge of the hill slopes. The upper ward was equipped with a cylindrical main tower, standing right next to the eastern wing of the castle, partly connected to it, and partly protruding from the face of the wall to the east. At a later stage, a zwinger could have been built in front of it, stretching in front of the south-eastern corner of the castle. The outer bailey was reinforced with at least four towers and gatehouses with an entrance on the western side at the end of the Middle Ages probably preceded by a barbican or some form of foregate, adjacent to the four-sided tower. The entire complex was connected to the town defensive walls, which were connected to the castle from the east and west.

Current state

The castle has not survived to this day. Only small brick and stone relics of the walls are visible. Admission to the former castle hill is free. Similarly, the remains of medieval town walls are visible on the surface in a rudimentary form. The best-preserved section is the fragment at Vabaduse Avenue, where the height of the wall in relation to the ground level, measured from the riverside part, is up to 5 meters.

bibliography:

Bernotas R., New aspects of the genesis of the medieval town walls in the Northern Baltic Sea region, Turku 2017.

Borowski T., Miasta, zamki i klasztory. Inflanty, Warszawa 2010.

Eesti arhitektuur 4, Tartumaa, Jõgevamaa, Valgamaa, Võrumaa, Põlvamaa, red. V.Raam, Tallinn 1999.

Herrmann C., Burgen in Livland, Petersberg 2023.

Laur M., Selart A., Dorpat/Tartu. Geschichte einer Europäischen Kulturhauptstadt, Wien 2023.

Rivo B., Medieval town wall of Tartu in the light of recent research, “Estonian Journal of Archaeology”, 15/2011.

Tuulse A., Die Burgen in Estland und Lettland, Dorpat 1942.

Tvauri A., Muinas-Tartu. Uurimus Tartu muinaslinnuse ja asula asustusloost, Tartu-Tallinn 2001.