History

The first, probably wooden church, was built on Toompea Hill just after the hillfort was captured by the Danes in 1219, during the crusade led by King Valdemar II the Victorious. In records, this church was first mentioned in 1233, when work on the stone building must have already been underway. Seven years after the first record, Valdemar II designated this Estonian “matrix ecclesiae” as the cathedral of the diocese, which was subordinate to the Lund Archbishopric. He also endowed the foundation and issued regulations regarding the payment of tithes to the Bishop of Rewal.

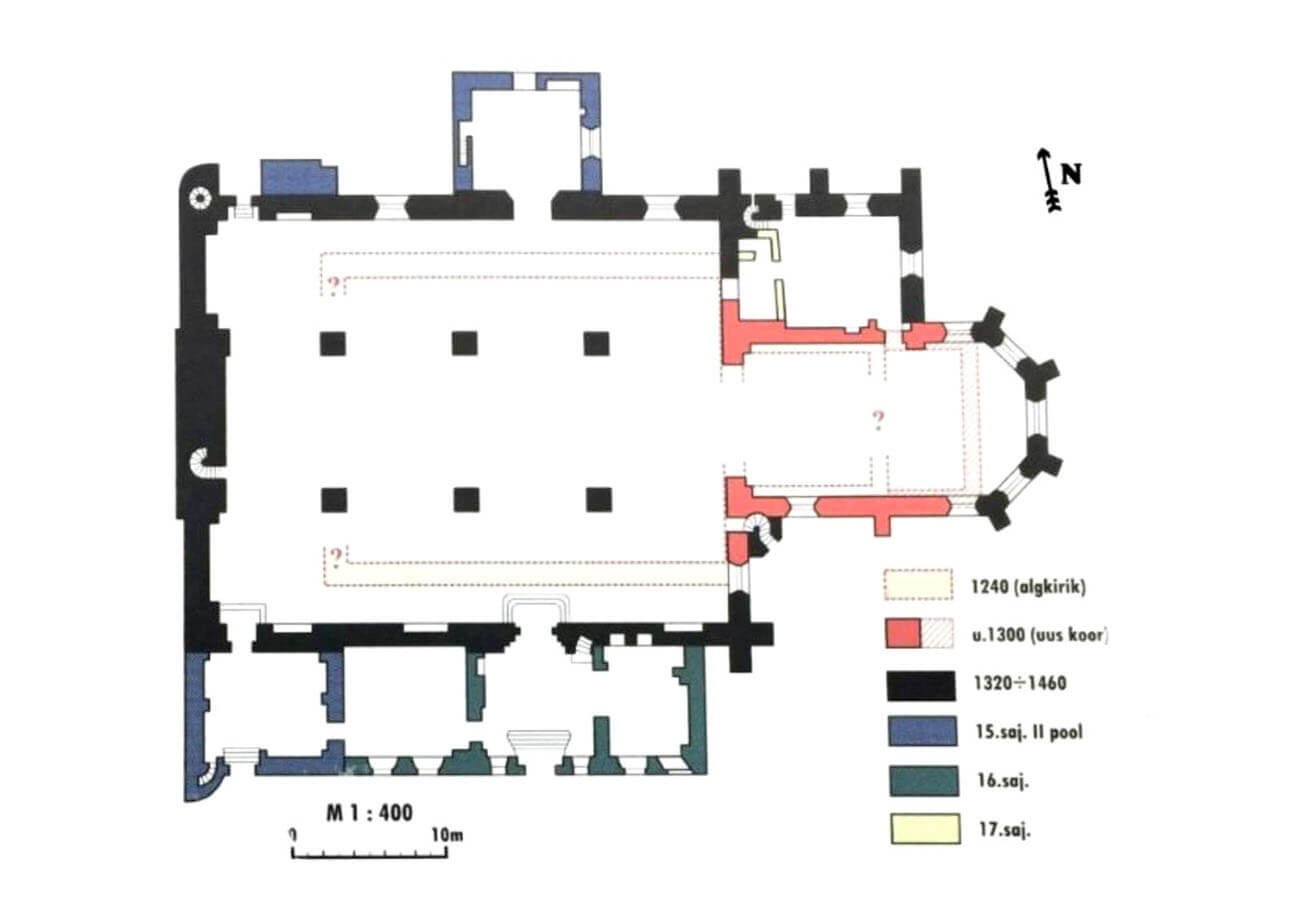

Construction work on the stone cathedral church began in the 1220s. The first stage was completed with the consecration in 1240, but the building continued throughout the 14th century and even in the first quarter of the 15th century. In 1319, King Eric VI Menved allocated funds for the construction of a cathedral church (“ad ecclesiae kathedralis fabricam”), which may have been connected with plans to add a polygonal closure to the chancel, a solution relatively rare in Estonia, or to expand the nave, although work probably began only after the sale of the northern part of Livonia to the Livonian Order in 1347. In 1325, King Christopher II confirmed the privileges of the cathedral, as did Valdemar IV in 1375. In 1389 and 1414, further construction work on the church was recorded in documents. It is not known how advanced works were, when in 1433 a great fire in the city also damaged the cathedral. Presumably, as part of the repairs, the last vaults were installed in the church nave, while at the turn of the 15th and 16th centuries the medieval construction process was completed with the construction of side chapels.

The cathedral remained in the hands of the Catholic clergy until the third quarter of the 16th century. The last owner of the Catholic diocese was Prince Magnus of Holstein until 1561, who died in Piltene in 1583 as Bishop of Courland. After him, Peter Foling became the first Protestant bishop. Probably with the change of relligion, the medieval furnishings of the church were partially removed, replaced with Renaissance and then Baroque ones. Around the middle of the 17th century, the church was covered with copper sheeting, half of which was financed by the Swedish Queen Christina. However, already in 1684, the church suffered significant damages during a city fire, when all the wooden furnishings were destroyed and part of the vaults collapsed. Reconstruction was carried out two years later, with funds collected from a special tax imposed by Charles XI. In 1778, the construction of an early modern tower was completed, and numerous modernization works were carried out on the chapels and interior until the 19th century. Later, mainly renovations took place, the most serious of which were in the years 1959-1961.

Architecture

The church was built more or less in the middle of an oval-shaped hill, on the south-west side occupied by a castle, and from the end of the 13th century surrounded by a defensive wall. Due to the central position of the cathedral, all the narrow streets running through the hill converged around it, and connected with the bishop’s court on the west side of the church, the canons’ curia to the south and residential buildings to the north-east. A larger free space was probably located by the cathedral from the south-east, where the street also ran towards the main gate and the road leading to the city at the foot of the hill.

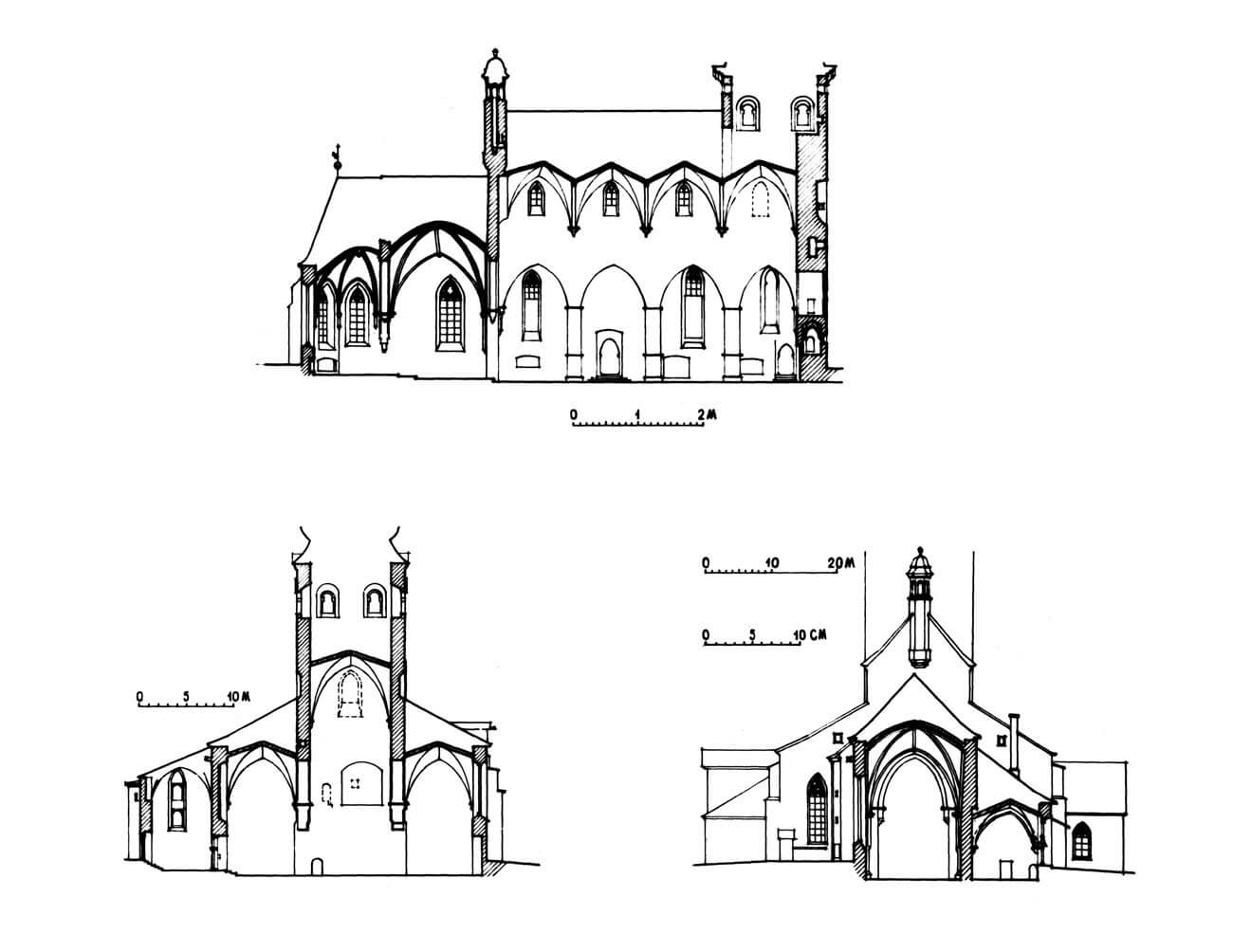

In the mid-13th century, the cathedral was a simple aisleless building with probably square chancel on the eastern side. At the beginning of the 14th century, a larger, early Gothic chancel was built, again with a straight wall to the east, although set on a semicircular foundation. In the second quarter of the 14th century, the building was expanded from an aisleless structure to a basilica with central nave and two aisles. The prolonged construction work was not completed until the 1430s, when the 23.1-metre-wide and 32.2-metre-long nave was completed. Its western part was extended by a shallow, 0.4 metres long projection in front of the elevation, but in the Middle Ages tower was not built above it. Originally, the church had only a slender polygonal turret with a high spire above the eastern gable of the nave. The early Gothic chancel was extended with a polygonal closure in the east and a two-bay sacristy was added to it from the north, built on the site of an older one from the 13th century. The church was supplemented in the late medieval period by side annexes: the northern chapel at the third bay from the west, the northern chapel at the first bay from the west and two or three southern chapels, as well as an annex at the south-west corner, originally perhaps used for storing tithes or goods, as indicated by the cargo openings on its upper floor.

From the outside, the nave, chancel and sacristy of the cathedral were supported with buttresses, only in the chancel situated at an angle. Some of the buttresses at the aisles were used during the construction of the chapels, when the side walls of the annexes were built on their extension. Between the buttresses there were large pointed and double splayed windows, originally filled with tracery with trefoils and quatrefoils popular in Gothic, from the 15th century also with motifs in the Flamboyant Gothic style. In the side aisles there were three-light windows, in the central nave two-light windows. Impressive three-light windows were pierced in the chancel from the south and on the axis from the east, while the remaining four were filled with two-light tracery. The entrances to the church were only from the north and west, because there was a spiral staircase in the thickened western wall. The most impressive, stepped pointed portal was set in the third bay from the west in the southern aisle. A characteristic element of the cathedral in the late Middle Ages was probably the bay window overhung on the western elevation of the nave, probably serving as a pulpit.

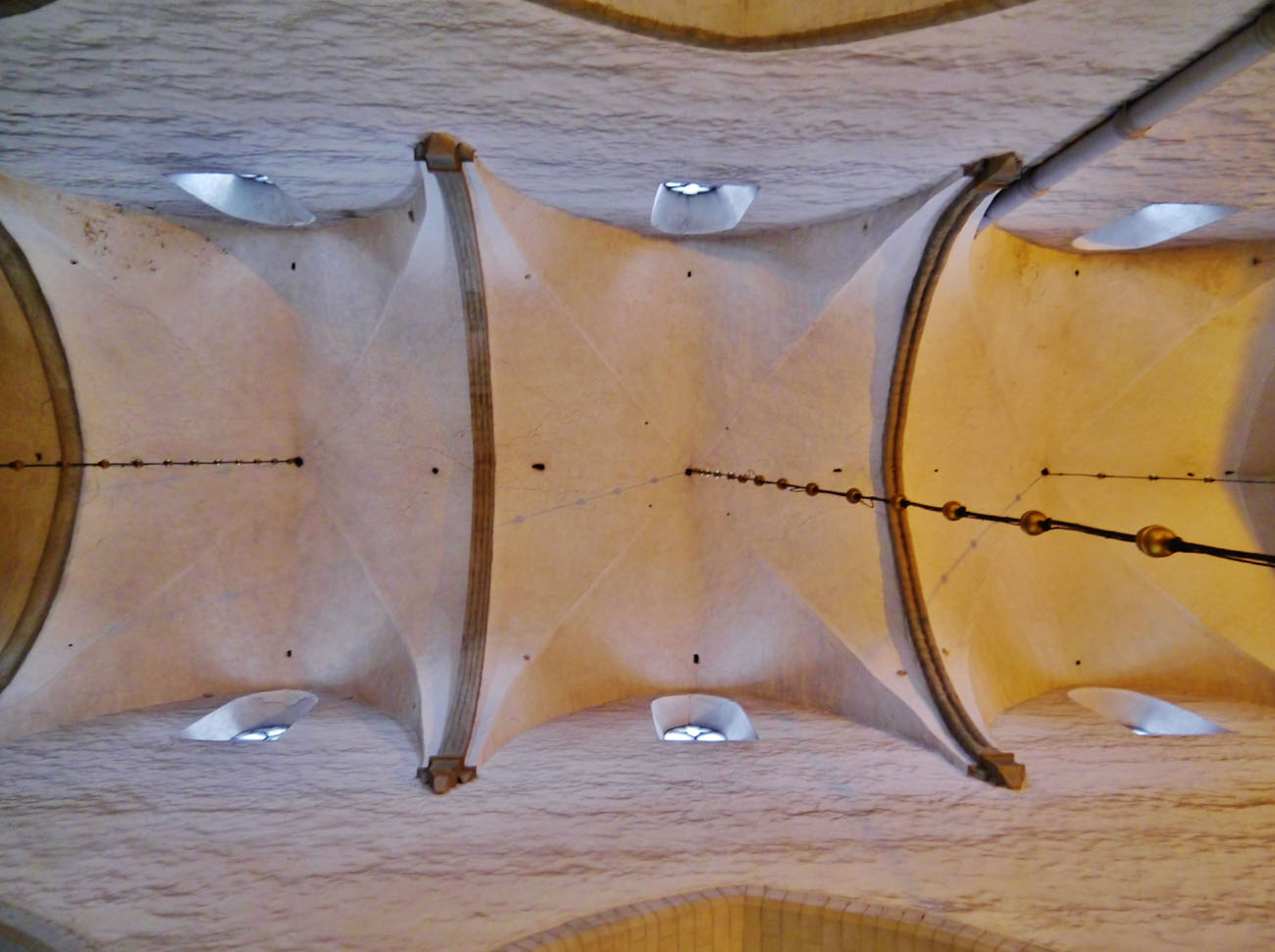

The interior of the nave was divided into aisles by means of three pairs of quadrangular pillars. From its imposts pointed arcades with chamfered archivolts were springing. At a height of less than 24 meters, a groin vault was built in the central nave, divided into four almost square bays and separated by transverse ribs. Similarly, in the aisles, the ribless groin vaults, built at a height of 14.3 meters, were divided by transverse ribs supported by highly suspended moulded corbels. The chancel was divided into a large square bay with an eight-part vault on moulded corbels and a polygonal apse covered with a sexpartite vault with ribs springing from the short shafts. Both parts were separated by a pointed arch band, while the entire chancel was separated from the central nave by an arcade with a stepped archivolt.

Current state

The cathedral has largely preserved its Gothic form from the 14th/15th century to this day, making it one of the most frequently visited architectural monuments in Tallinn. The north-western chapel has not survived, of which a bricked-up arcade is still visible. The western tower is an early modern addition, and the southern chapels have also been thoroughly rebuilt in the early modern period. Despite the fires, numerous architectural details have survived, including portals, windows with tracery (renovated in the second half of the 19th century), and the richly decorated sacramentary niche in the northern wall of the chancel. The vaults have survived, although the details of their support system suffered significantly during the fire of 1684 (wall shafts, corbels, consoles, arches). Inside the church there are numerous tombstones, mostly early modern, but the oldest ones date back to the 14th century (a tombstone with an image of a chalice and a hand, a damaged tombstone of Woldemar Sorseveri).

bibliography:

Laast M., Tallinna Piiskopliku Toomkiriku irdraiddetailide inventeerimine, konserveerimine ja eksponeerimine, Tallinn 2022.

Neumann W., Nottbeck E., Geschichte und Kunstdenkmäler der Stadt Reval, Zweiter Band, Reval 1904.