History

The first record of Otepää (German: Odenpah) was in 1116, referring to the local pagan hillfort. At that time, the Ruthenian Prince Mstislav captured a stronghold called Bear’s Head, from which the later name of the castle was supposed to come, as “ott” in the local dialect meant head. The hillfort was one of the most important seats of the Finno-Ugric tribe of Ugandi, which is why it was besieged by the troops of German crusaders in 1208 and by Ruthenians in 1210. In the same year, it was captured by the Livonian Order, which in 1216, together with the troops of the Bishop of Riga, strengthened the fortifications. However, the following year, the Ugandis with the help of the Ruthenians, recaptured Otepää.

The brick Odenpah Castle was built by Bishop Hermann von Bekeshovede after the hillfort was captured by the crusaders in 1224. The construction work must have been carried out very efficiently, because a year later strong fortifications were recorded (“Castrum Odempe, novis habitatoribus inhabitatum invenit et firmiter aedificatum”). Works were probably completed under Hermann’s successors, Bishop Alexander or Friedrich von Haseldorf. It is likely that the castle was planned to be one of the main episcopal seats, because it was not a border or roadside watchtower. However, despite numerous efforts, Odenpah never played a significant role. The reason for this state was the change in the direction of trade routes and the dynamic development of Dorpat, located on the Emajõgi River, to which the capital of the diocese was eventually moved.

The war between the Teutonic Knights and the Bishop of Dorpat proved fatal to the castle, during which in 1396 the besieging Teutonic Knights managed to set fire and destroy the castle. The ruined structure was never fully rebuilt, although the castle buildings were recorded in documents still in 1477. Ultimately, the bricks and stones from castle served as free building material for the local population.

Architecture

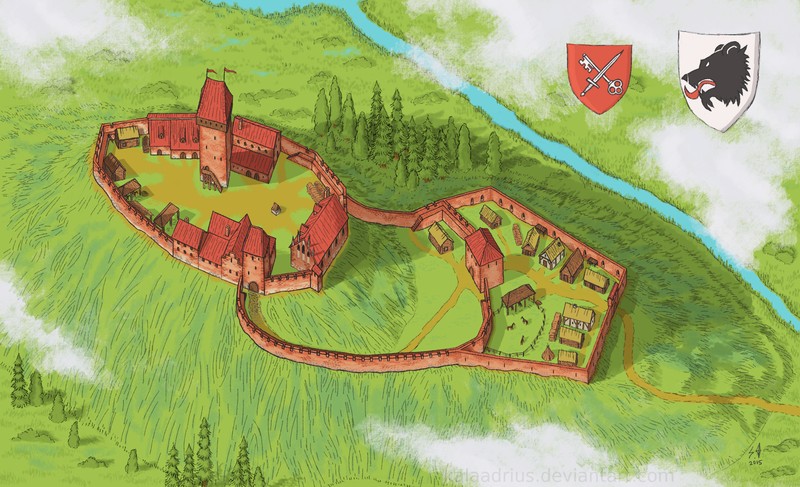

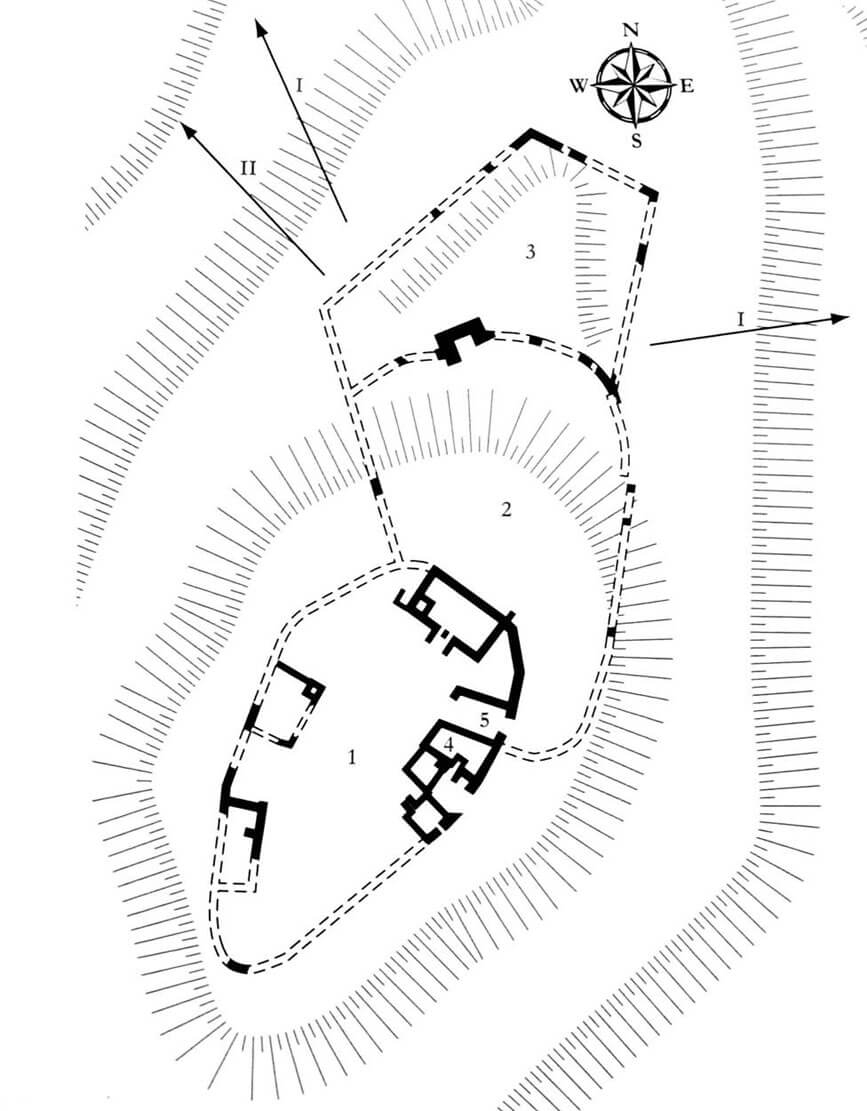

Odenpah Castle in its most developed form consisted of an upper ward, situated on the site of an older hillfort on the top of the hill, as well as two fortified baileys protecting it from the north, located lower, at the base of the hill. The hill was characterized by steep and high slopes on practically every cardinal side. At their foot on the western side, a river could originally flow, while on the north-east there were marshy areas with numerous lakes.

The defense of the upper ward was provided by a wall running along the edge of the slopes, in a plan having a shape similar to an almond, with a narrowing in the south-western part. The main gate of the upper ward was located on the eastern side in the northern part of the courtyard, from where it led to the middle bailey. The gate was located in a quadrangular building or tower with a passage on the ground floor, located entirely inside the courtyard. Most of the residential buildings of the upper ward were attached to the perimeter wall, especially on the eastern and western sides, although a large building with a vestibule was located in the northern part. The central element of the castle may have been the quadrangular, free-standing main tower.

The economic and utility buildings of both baileys, similarly to the main part of the castle, were probably attached to the inner faces of the walls, but were mostly wooden or half-timbered structures. The massive gatehouse of the middle bailey had a brick form, built on a rectangular plan with longer sides parallel to the defensive wall. None of the baileys were probably reinforced with towers. The outer bailey was distinguished by streight curtains with sharp corners, in contrast to the rounded corners of the middle bailey and the upper ward.

Current state

Today, from the castle you can see only the outline of the foundations on the top of the hill, protected during archaeological works. During this period, many interesting finds were discovered, including one of the oldest examples of hand-held firearms in Europe, cast in bronze before 1396. Entrance to the castle area is free.

bibliography:

Borowski T., Miasta, zamki i klasztory. Inflanty, Warszawa 2010.

Herrmann C., Burgen in Livland, Petersberg 2023.

Tuulse A., Die Burgen in Estland und Lettland, Dorpat 1942.