History

Church of St. Michael in Jõhvi first appeared in records in 1367, in connection with the invasion of northern Livonia by the troops of Novgorod the Great. It must therefore have been built earlier, probably in the mid-14th century. Due to its location near the border, it was very vulnerable to destruction caused by armed conflicts. There was little arable land and human habitations between Narva and Jõhvi, so when invading troops crossed the river near the settlement, the church of St. Michael was the first place worth attention. For this reason, in the Middle Ages the church acquired defensive features.

In 1426, the Cistercians sold their land in the parish of Jõhvi to the Livonian branch of the Teutonic Knights, which from that moment had patronage over the church. It was rebuilt at the end of the 15th century or at the beginning of the 16th century. A tower was then added, the interior was perhaps vaulted, and the whole was fortified again. For this reason, during the Livonian War, in the first days of 1558, residents from nearby settlements were said to have taken refuge in the church and with the participation of four unknown Germans, defended it so effectively that they survived the assault of a three-hundred-strong unit of soldiers of Tsar Ivan the Terrible. However, when the invaders returned after about a month with reinforcements and heavier weapons, and the Germans were no longer in Jõhvi, the church was captured. According to tradition, over a hundred peasants and their families died there.

In the early modern period, the church was destroyed during the Swedish-Russian War in 1657 and during the Great Northern War in 1703. In 1728 it was rebuilt, and in 1748 it received a Baroque finial of the tower, replaced in 1875 with a neo-Gothic one. The last war damage affected the historic building in 1941. The church remained in ruin for quite a long time, as it was rebuilt only in 1984.

Architecture

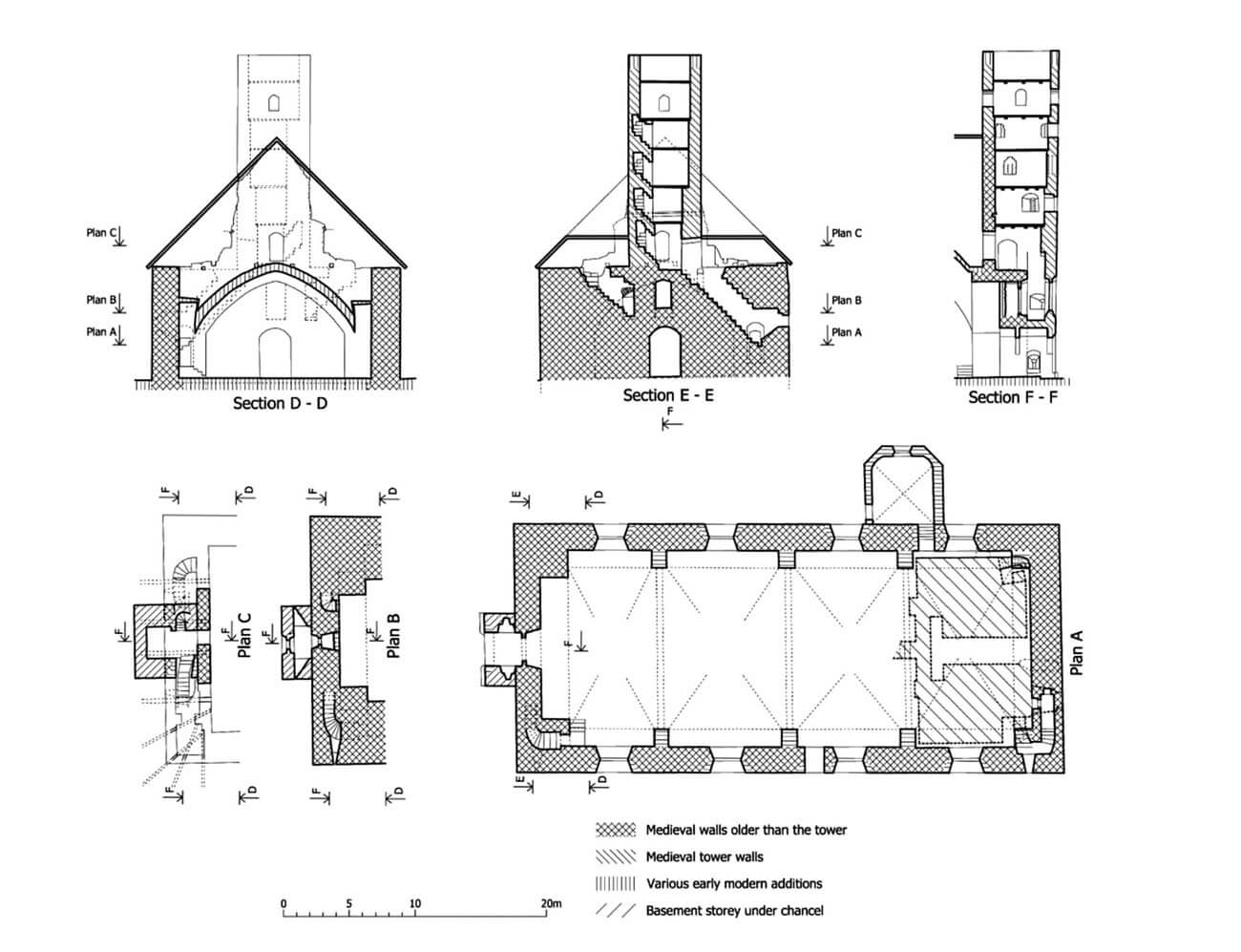

The church of St. Michael was built as an exceptionally large aisleless building, with internal dimensions of 35.1 x 13.8 meters, erected on a rectangular plan without a separate chancel. As it had defensive functions in the Middle Ages, it had small, narrow windows and was surrounded by an earth rampart with a palisade. Presumably, as early as the 14th century, it had hoardings or wooden defensive porches running around the external facades of the church, and a place was created above the vault, where the local population could possibly take shelter. At the turn of the 14th and 15th centuries, a tower of a defensive and observation function was added on the western side, partially embedded in the nave.

The external facades of the church were plain, separated only by lancet windows. The church walls were not supported by buttresses from the outside, but in a way rarely seen in Estonia, the massive buttresses were pulled into the interior of the building, where a vault was based on them, creating impressive, approximately 2-meter-wide ogival arcades between the bays. Perhaps the vault was built only as part of the reconstruction at the end of the 16th century, because only two western corner buttresses were built together with the perimeter walls of the nave, and the rest was inserted secondarily (presumably, two massive buttresses were also located in the eastern part of the nave, but at the time of construction of the vault it were replaced by slimmer ones).

The gable of the nave rested unusually on the western buttresses, which itself became the rear wall of the tower added in the 15th century. In front of the gable wall, there was a breastwork wall, and the space between them was divided into two small rooms connected by a door opening. Holes were punched through both the gable wall and the breastwork, in which beams supporting the external hoarding were embedded. The gable wall could have served as a fire barrier. If the roof over the nave burned down, theoretically the small rooms west of the gable could survive. Similarly, burning the hoarding porch did not automatically mean a fire in the main part of the church. If the attackers captured the nave (without the attic), the defenders could theoretically continue their resistance in the gallery and in the rooms west of the gable. The rooms themselves could be used to store ammunition, small weapons and gunpowder. Being isolated from the rest of the structures, it would be very suitable for this role, especially since rooms were built before the tower was erected, and the tower was not built after the complete demolition of the hoarding, but was somehow incorporated into its defense system. Significantly, there were no windows or loopholes on the third floor of the tower, unlike all other floors. In this way it was probably deliberately isolated from the hoardings, either for defensive purposes or simply for fire safety reasons. It is very possible that a similar arrangement of the gable and breastwork also functioned symmetrically on the eastern side of the church.

Inside the church, under the altar, there were two basement rooms serving as a crypt and a chapel, originally covered with a ceiling, then vaulted. Two passages led to them from the presbytery part of the church. This solution, derived from the Romanesque tradition, was quite unusual and rare in Estonia. Thanks to the crypt, the floor of the church’s presbytery was raised by about 1 meter in relation to the nave. In its south-eastern part, within the thickness of the wall, there were stairs leading to the attic. The second staircase was hidden in the wall in the southwestern part of the nave.

Current state

Today, the church is one of the largest survived Gothic, aisleless churches in Estonia and what’s more, it is the only one in which the functioning of a medieval hoarding has been confirmed, along with a unique system of a recessed gable creating space for a breastwork and two small rooms. Currently church is adapted to visits, there is a museum in it, placed in two underground rooms, presenting archaeological finds, among others the oldest metal elements from Estonia from the tombs in Jäbara. The church also hosts concerts due to its excellent acoustics.

bibliography:

Alttoa K., Bergholde-Wolf A., Dirveiks I., Grosmane E., Herrmann C., Kadakas V., Ose I., Randla A., Mittelalterlichen Baukunst in Livland (Estland und Lettland). Die Architektur einer historischen Grenzregion im Nordosten Europas, Berlin 2017.

Kadakas V., Jõhvi church – a peculiar fortification seized in the Livonian War near Narva, “Castella Maris Baltici 8”, Riga 2007.