History

The oldest castle was built in Narberth as part of the Anglo-Norman conquest of Wales, in the early medieval region (commote) of Cwmwd Arberth led in the late 11th century by Roger and his son Arnulf de Montgomery. The construction of the wood and earth castle may have taken place in the 1190s or in the first decade of the 12th century, when there was no formal division of the conquered lands and their boundaries had not been marked. The founder of the castle may have been one of Arnulf’s liegemen or a feudal lord directly subordinate to the English king, because in a document of King Henry I from around 1130, he allowed the extraction of timber from “our forest of Narberth”. The castle may have been built by the Earl of Shrewsbury, Robert Bellême, and then passed directly into the hands of the king, who captured his lands in 1102. The castle was built as one of a number of strongholds to secure Anglo-Norman rule and formed part of the Landsker Line, a series of fortifications that marked the 12th century extent of Anglo-Norman expansion.

In 1116 Narberth was attacked and burned by the Welsh. The then timber ringwork or motte castle was not permanently captured by the Welsh chieftain Gruffudd, son of the Dyfed king Rhys ap Tewdwr, because they were soon forced to withdraw by the Anglo-Norman army of Henry I. Around 1138-1140 it passed into the hands of Henry FitzRoy, the illegitimate son of King Henry I, via his Welsh mistress Nest, daughter of Rhys ap Tewdwr. This was despite the fact that it had been part of Gilbert de Clare’s holdings, since King Stephen created the earldom of Pembroke, as part of a strategic plan to allocate a large number of lordships to trusted supporters of the king. Henry FitzRoy titled himself Lord of Narberth and probably ruled his estates from Narberth Castle, which he may have held until his death in 1157.

In 1159 and 1215 Narberth was again attacked by the Welsh. On both occasions the castle may have been burnt down, but even if this happened, it was quickly recaptured and rebuilt. Furthermore, at the time of the great Welsh rebellion of 1189 Narberth was one of the few Anglo-Norman strongholds remained in western Wales until 1193. Llywelyn ap Lorwerth’s conquests of 1215 were formally recognised three years later, but in 1220 he again attacked the recently rebuilt castle at Narberth, captured it and razed it, killing some of the garrison and taking others prisoner. Later that year a royal order was sent to the Norman settlers of west Wales to assist William Marshal II, son of the recently deceased earl, in repairing his castle at Narberth. Marshal arrived in Pembrokeshire in 1223 to enforce royal control over the Anglo-Normans and consolidate his lands. He held Narberth until his death in 1247, when his estates were divided among a number of heirs. The lordship of Narberth passed to Roger Mortimer, Lord of Wigmore, through his marriage to Maud de Braose, daughter of Eva Marshal.

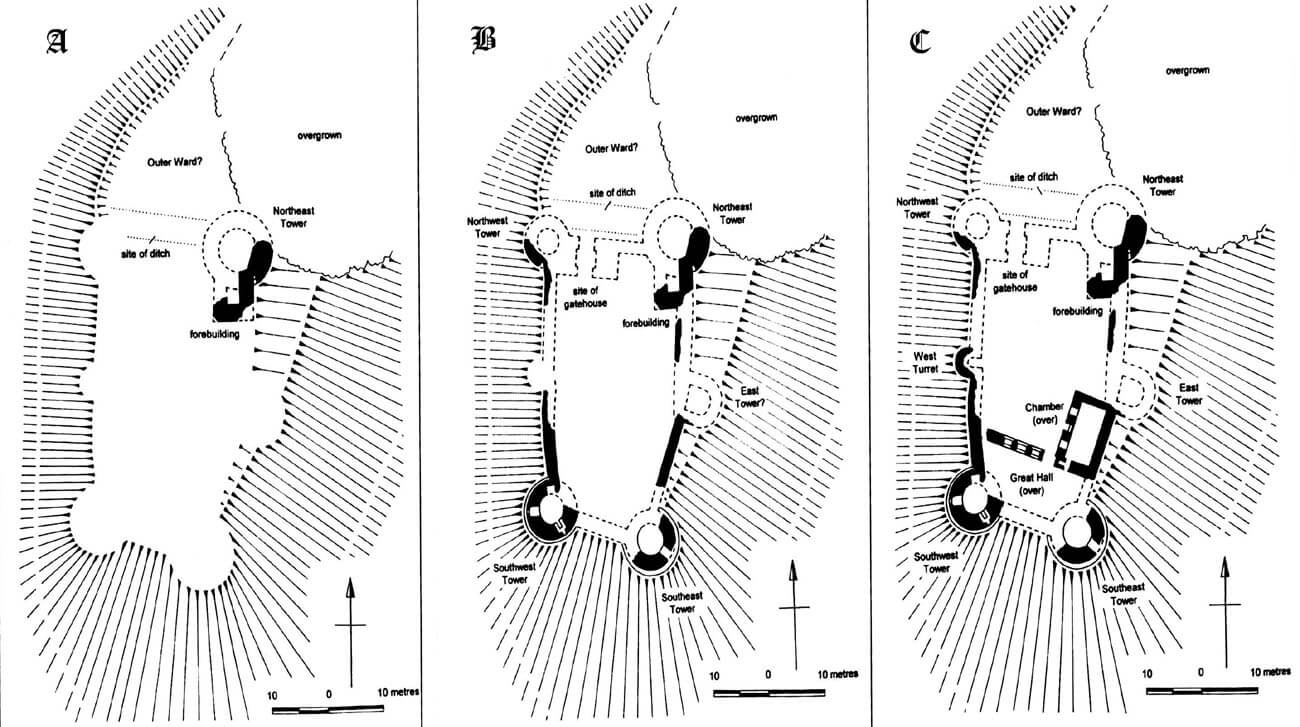

In 1257 the castle was destroyed by Welsh forces led by Llywelyn ap Gruffudd, Prince of Gwynedd, and during the fights Henry Wingan, Mortimer’s steward of the castle, was killed. After reclaiming the ruined stronghold, Mortimer began rebuilding it, but this time stone was used for the first time. and builders reached the latest achievements in military architecture in the mid-13th century. Roger Mortimer died in 1282, probably witnessing the completion of the castle’s reconstruction.

Mortimer’s widow, Maud, gave Narberth to her younger son Roger Mortimer of Chirk. In his time south-west Wales was not directly affected by the great Welsh Wars of Independence or the Welsh rebellion of 1294-1295, but occasional discontent still broke out in armed rebellions. During one such episode, while Mortimer was serving the king in Gascony in 1299, Narberth Castle was burned down again. The extent of the damages was not recorded in documents, although Mortimer complained to the king that some of his men had been killed. Presumably as part of the subsequent repairs, additional housing was built on the castle. The castle was fully repaired by 1330 at the latest, when an survey of the goods and furnishings inside it was made (among others, the castle was said to have contained a trebuchet, or stone-throwing machine).

In 1322 Roger Mortimer of Chirk supported the Earl of Lancaster’s rebellion against King Edward II. After the defeat of the rebellion he lost Narberth and was imprisoned in the Tower of London, where he died in 1326. The castle passed through several owners, including Robert de Hasley and then Henry Gower, Bishop of St Davids, before being restored to the Mortimer family in 1354. During the French invasion scare of 1367, the king’s constable was ordered to garrison Narberth Castle, as was done at many other castles over the next two decades. In 1389 there was an incident that ended with the pardon of Thomas Fort of Llansteffan, who was blamed, among other things, for revealing the secrets of Narberth Castle to the enemies. Narberth was then ruled by an English king, due to the death in 1382 of Philippa, widow of Roger Mortimer, and the absence of majority of the next Roger of the Mortimer until 1394.

In 1402 the castle was again confiscated when Edmund Mortimer allied himself with Owain Glyndŵr during his Welsh rebellion. Thomas Carew was made lord of the castle for life, and in 1404 he successfully defended Narberth against Welsh rebels, prompting Henry IV to reward him with the grant of the castle. Narberth was restored to the Mortimer family in 1413 by Henry V. However, when Edmund Mortimer died without issue in 1422, the castle returned to the English king. Lack of landowners led to the building falling into disrepair, with its premises described in 1424 as being in ruins. Eventually Henry VI granted the castle to Richard, Duke of York, who leased Narberth to John de la Bere, Bishop of St Davids, and Gruffudd ap Nicholas, Deputy Justice of South Wales. Gruffudd clearly considered himself Lord of Narberth, but apparently unjustly, for in 1453 Walter Devereux was granted part of the castle on behalf of the Duke of York, who owned the estate until his death at the Battle of Wakefield in 1460. The castle then remained in the possession of the Crown until Henry VIII granted it and the title of lord in 1515 to Sir Rhys ap Thomas, owner of Carew. By this time, however, the building was in a poor state and gradually fell into ruin. In 1539 Narberth Castle is said to have been still inhabited, but largely destroyed. Its last known inhabitant, the tenant Richard Castle, is said to have resided at the castle in the third quarter of the 17th century.

Architecture

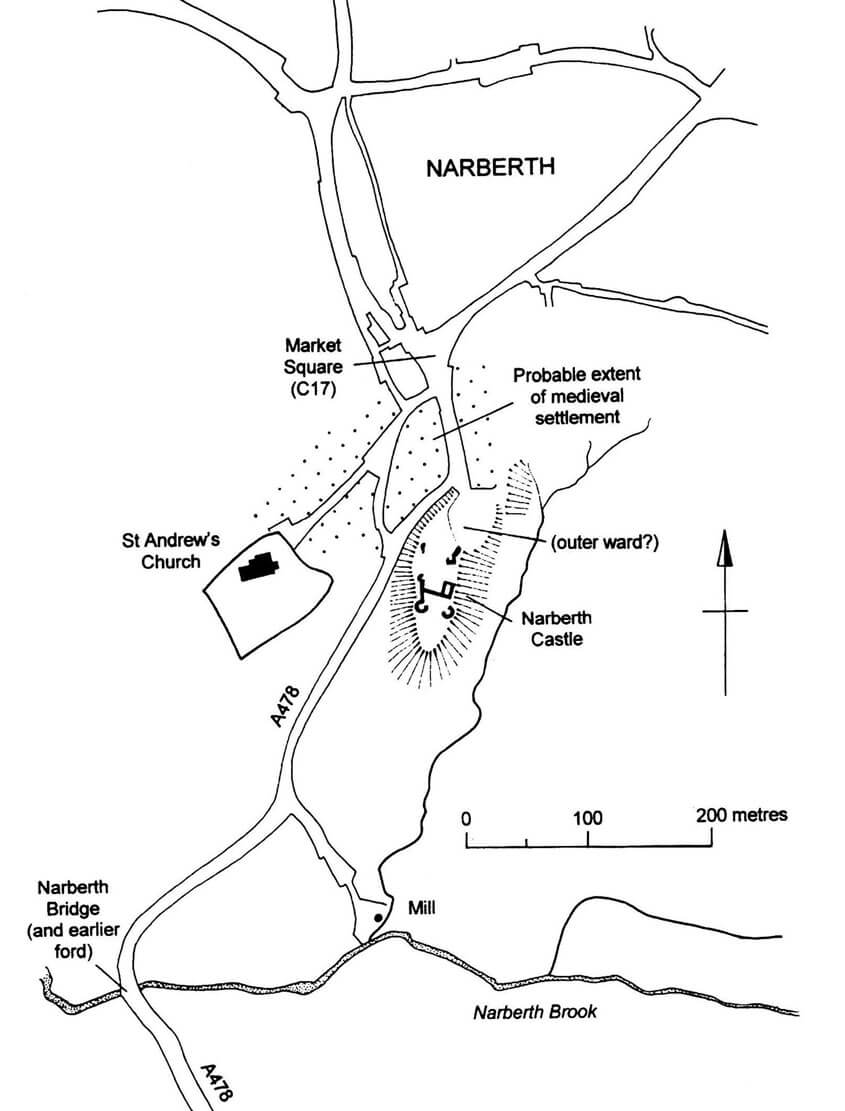

The stone castle from the 13th century was built on an elongated hill, limited from the east and west by narrow valleys, directed south towards the Narberth Brook, where in the Middle Ages there was a mill and a nearby crossing. From the river side in the south, the slopes of the hill were the highest and steepest. The gentlest approach was from the north, where a small settlement with the church of St. Andrew developed, and in the immediate vicinity of the castle a small wooden outer bailey, approximately 40 x 30 meters in size. An important route probably ran west of the castle, connecting the settlement with the river crossing.

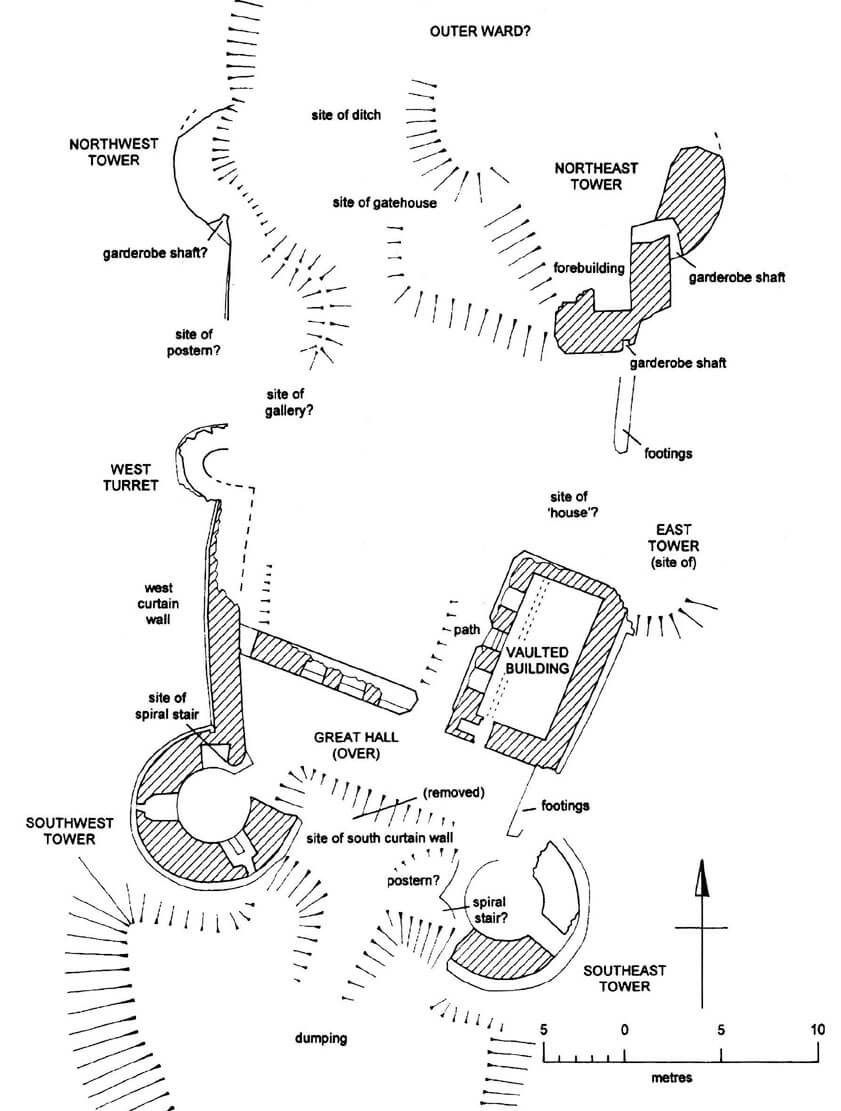

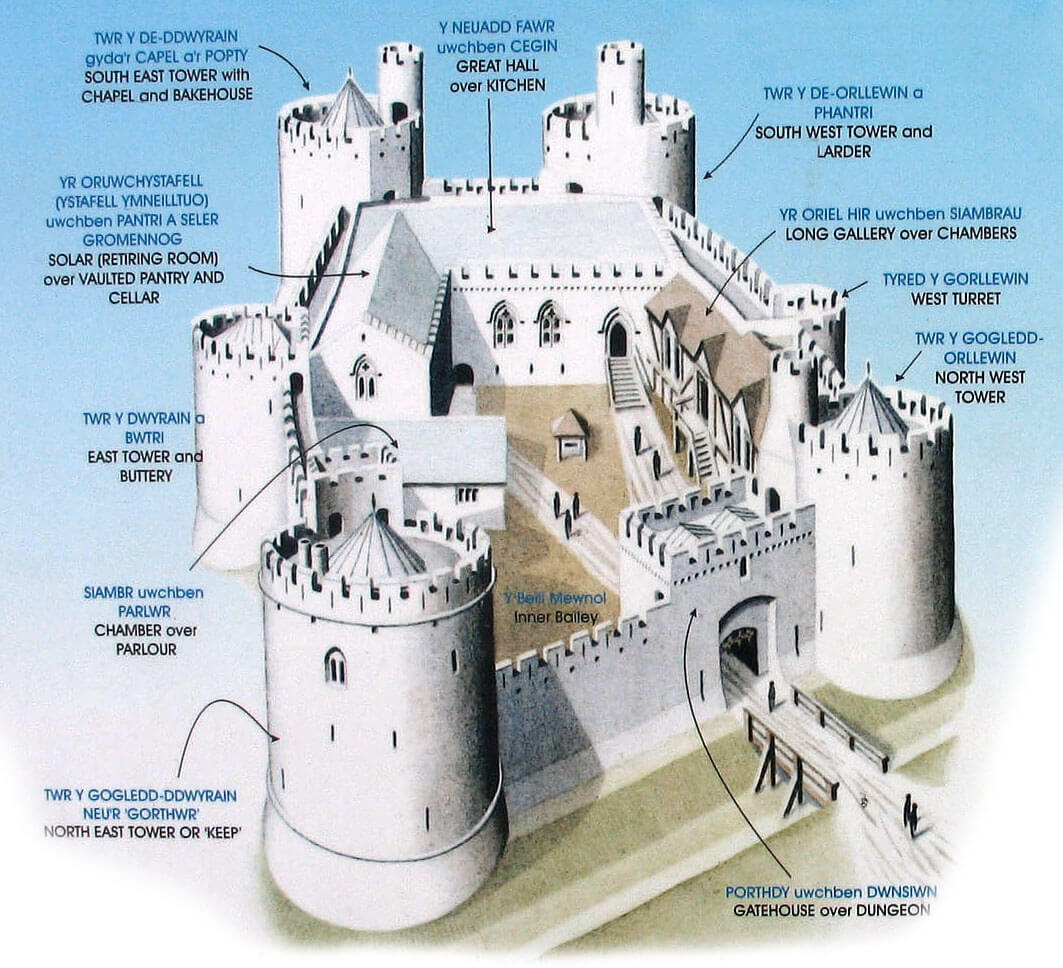

The core of the castle in the plan was adapted to the form of the terrain, so it was extended on the north-south line. After leveling the top of the hill, the perimeter of the defensive wall was built on the plan of an irregular polygon, separating a courtyard measuring approximately 45 x 25 meters. The perimeter of the defensive wall was reinforced at the corners with four cylindrical towers, of which the north-eastern one was much larger and probably served as a keep. The eastern and western sections of the wall were additionally reinforced by single semicircular towers, while the western one, the smallest one and the only one full on the ground floor, could have been built as a result of later expansion. All of the above defensive works were strongly pushed out in front of the neighboring curtains, especially the smaller side towers, flanking long sections of the wall. The entrance gate to the castle was located between the two northern towers, in the gatehouse probably located entirely on the courtyard and not protruding from the perimeter of the defensive walls. According to a record from 1539, it was to consist of an entrance passage flanked by two chambers, one of which contained a prison in the basement and a chamber above it. The gatehouse was to be about 13 meters from east to west and 5 meters from north to south. The outer defence zone was a dry moat, probably dug only from the side of the castle outer bailey in the north.

The tower – keep, which until the 14th century played the main residential and representative function at Narberth Castle, was to contain three residential floors above the utility ground floor. In addition to the circular core with a diameter of about 12-15 meters, it was enlarged from the south by a quadrangular projection, probably at the level of the first floor housing the entrance, and in the ground floor an auxiliary door. The lower part of the keep was widened by a prominent plinth with elevations sloping towards the inside, separated from the vertical part of the elevation by a string cornice. The thickness of the keep wall was also greater in proportion to the diameter, oscillating around 3 meters wide in the ground floor. The crown of the keep walls could be topped with a crenellated parapet, behind which a conical roof could surrounded an openede wall-walk. The adjacent curtains of the defensive wall were certainly lower than the keep, so they must have been connected to its interior at the level of the third or fourth storey. The interiors of the keep were equipped with fireplaces and latrines, the latter with shafts for feces led through the thickness of the wall, where they emptied collectively into a square chamber at the foot of the wall. Due to its defensive nature, the openings in the keep probably had the form of slits intended for firing. Only one or two of the highest storeys could have had a few larger windows.

The southern towers had a total diameter of 10 meters and an internal diameter of 5 meters at ground level, with walls about 2.5 meters thick. In the unvaulted, three-storey interiors of the southern towers, gradually increasing due to the offsets of the walls between the floors, there were fireplaces and latrines. Probably similar equipment was also in the north-western tower, which also had a diameter of about 10 meters and walls about 2.5 meters thick at ground level. In the late Middle Ages, the south-eastern tower housed a bakery in the ground floor and a chapel on the first floor, while the eastern tower was supposed to have housed a buttery. The heated rooms in the smaller towers could have been intended primarily for the garrison and less important members of the owners’ family or their subordinates. From the outside, the corner towers could have resembled a keep, only it were less massive and probably slightly lower. In addition, their base parts were not covered with string cornices. It may have been topped with cylindrical turrets, popular at that time in Anglo-Norman Wales, placed on the extensions of spiral staircases.

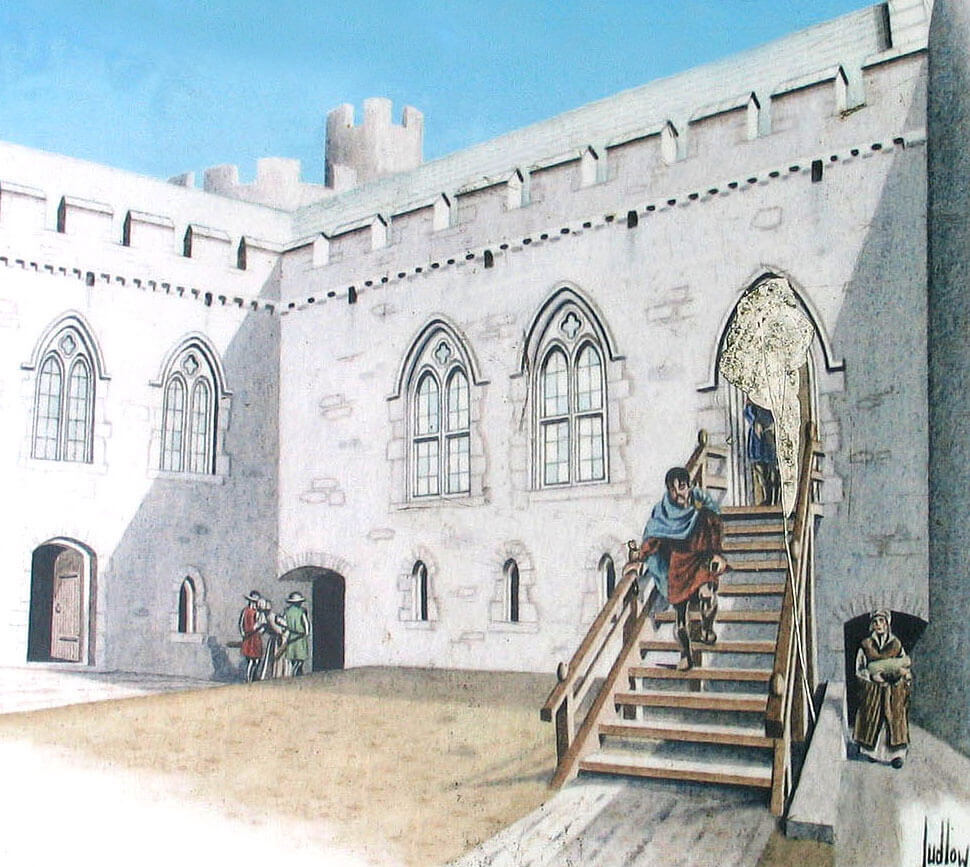

Around the turn of the 13th and 14th centuries, a large L-shaped building was erected in the southern part of the courtyard, adjoining the inner walls of the defensive walls and towers with two wings. The smaller eastern wing, measuring 12 x 8 meters, had a large private chamber (solar) on the first floor, and a vaulted kitchen with a pantry on the ground floor. Both rooms were not directly connected, so an external, probably wooden porch must have led to the upper room. The ground floor of the southern wing was also intended for utility purposes, and above it there could have been a representative hall, similar to the great hall of the nearby Llawhaden Castle. None of the storeys of the southern wing were covered with a stone vault. It had a trapezoidal plan with an average length of 20 meters from east to west and 8 meters from north to south. From the courtyard side, both wings on the lowest storey were probably lit by narrow slits, while larger windows were placed at the level of the first floor. The latter could had pointed heads or segmental arches, similarly to the castles of Herlach or Beaumaris. A narrow wing was also supposed to be located in the western part of the courtyard, where an long gallery was supposed to have been built at the beginning of the 16th century.

Current state

The castle has survived in poor condition to the present day. The best visible are the ruins of two southern towers preserved to the level of the third floor, and the relics of the southern building with one preserved vaulted room. A fragment of the hall wall, about 10 meters high from the courtyard side, and a section of the wall closing it from the west have also survived. A fragment of the keep is visible on the northern side. The earth fortifications, visible among others in the area of the former outer bailey, may date back to the original castle from the beginning of the 12th century. Most of the preserved walls have lost their face, with the exception of the two southern towers. Narberth is currently a property managed by Pembrokeshire County Council and is open to visitors all year round.

bibliography:

Kenyon J., The medieval castles of Wales, Cardiff 2010.

Ludlow N., The castle and Lordship of Narberth, “Journal of the Pembrokeshire Historical Society”, vol. 12/2003.

Salter M., The castles of South-West Wales, Malvern 1996.

The Royal Commission on The Ancient and Historical Monuments and Constructions in Wales and Monmouthshire. An Inventory of the Ancient and Historical Monuments in Wales and Monmouthshire, VII County of Pembroke, London 1925.