History

In the 11th century Wales was a collection of small, often warring principalities and kingdoms that had no clearly defined borders and whose Celtic rulers did not conduct a common policy. This situation facilitated the conquest of Anglo-Norman lords, who had great authority and independence from the English king in their border marches. One of them, Roger de Montgomery, Earl of Shrewsbury, took control of south-west Wales in 1093, taking advantage of the death of the Welsh king of Deheubarth, Rhys ap Tewdwr. Roger built the first wood and earth castle called Din Geraint near the mouth of the Teifi, but his death in 1094 meant that the Welsh soon regained their conquered lands and destroyed the castle.

In 1107, Owain ap Bleddyn, son of the then Welsh king of Deheubarth, Gruffydd ap Rhys, abducted Princess Nest, whose marriage was to seal a Welsh-Norman alliance. In response, the English king Henry I authorized Gilbert FitzRichard de Clare to take military action. In 1110, FitzRichard captured Cardigan and founded a new settlement and castle on the border between Anglo-Norman-held Pembrokeshire and independent Welsh Ceredigion. The castle was to control the crossing of the River Teifi, and the town inhabitants were granted special privileges to encourage more settlers, who might be willing to fight for the new lord.

When in 1135 the English king Henry I died without a male descendant, it caused an outbreak of civil war between the king’s daughter, Matilda, and her cousin, Stephen of Blois. Taking advantage of the Anglo-Norman situation, the Welsh came out armed and in the shortest time took over the majority of strongholds in the region. Richard Fitz Gilbert, Gilbert’s son, was killed in a Welsh ambush, and the Norman army was defeated at the Battle of Crug Mawr in 1136. Cardigan remained the only stronghold in Ceredigion that was not taken over by the Welsh. Attempts to obtain it in 1138 and 1145 ended in failure, only the town was burnt. The castle fell into Welsh hands only in 1165, when it was captured by Rhys ap Gruffydd. He made a deal with king Henry II, who confirmed his right to the lands of Deheubarth, providing the acceptance of Norman rule in Pembrokeshire. Rhys also allowed Anglo-Norman settlers to remain, provided they agreed to be subject to Welsh law. Castle Cardigan was rebuilt in stone and it was the first recorded stone castle built by the Welsh prince. In 1176, the castle also made history, because it held the first known eisteddfod, that is Welsh festival of literature, music and performances.

Rhys ap Gruffydd died unexpectedly in 1197. Three years later Cardigan was sold to the English by Maelgwn, Rhys’s illegitimate son, who was at odds with his rightful heir. Although the castle was extended by king John in 1205 and 1208, it was the Welsh ruler Llywelyn ap Iorwerth who managed to get it in 1215, using the First Barons War in England. Cardigan was recaptured by William Marshall, the second Earl of Pembroke in 1223, but already in 1231 it changed its owner again, due to Maelgwn’s ap Rhys conquering. Eventually, the castle was conquered by the English in 1240, extensively rebuilt by Walter Marshal and then by Robert Waleran, who managed the castle after Marshal’s death in 1241. During Robert’s rule over Cardigan, town walls were also erected. Subsequent modernizations were introduced in 1321, but they were the result of fears of the rebellion of English barons, not the new Welsh war. The expansion of the castle, however, proved to be useful at the beginning of the fifteenth century, when the uprising of Owain Glyndŵr broke out. His forces attacked Cardigan in 1405, but despite considerable damages, the castle survived. The rebellion was suppressed in 1409, and repairs were carried out in the following years, despite the fact that the Cardigan’s military significance diminished. The castle remained merely an administrative centre, with the town increasingly declining throughout the 16th century.

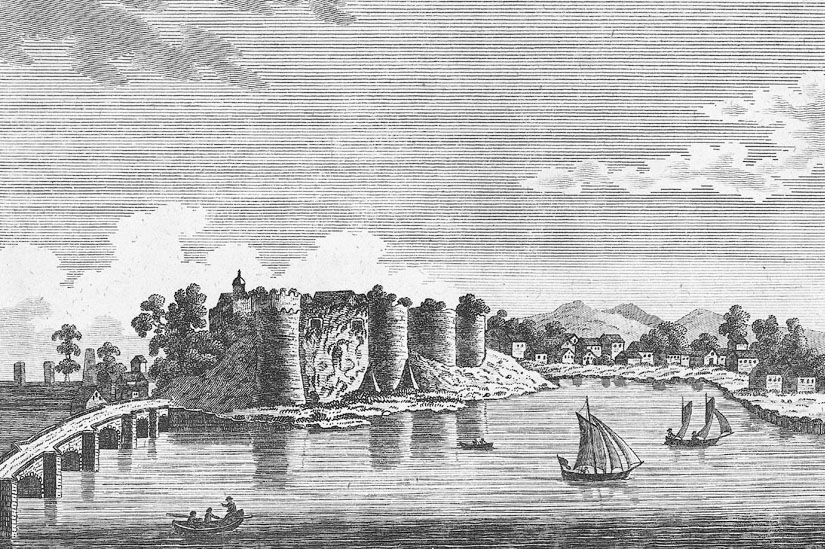

The outbreak of the English Civil War in 1642 meant that the castle was quickly adapted to defend by royalists, who built an embankment on the walls of the castle to use artillery. In 1644, the victory began to tilt in favor of Parliament, and Cardigan attacked forces under General Rowland Laugharne. During the siege, which lasted two weeks, Parliamentary artillery made a breach within the walls and then the castle was stormed. After the war, the destroyed stronghold was additionally deliberately slighted to prevent further military use, the castle was also used as a source of free stone, during the reconstruction of the city.

Architecture

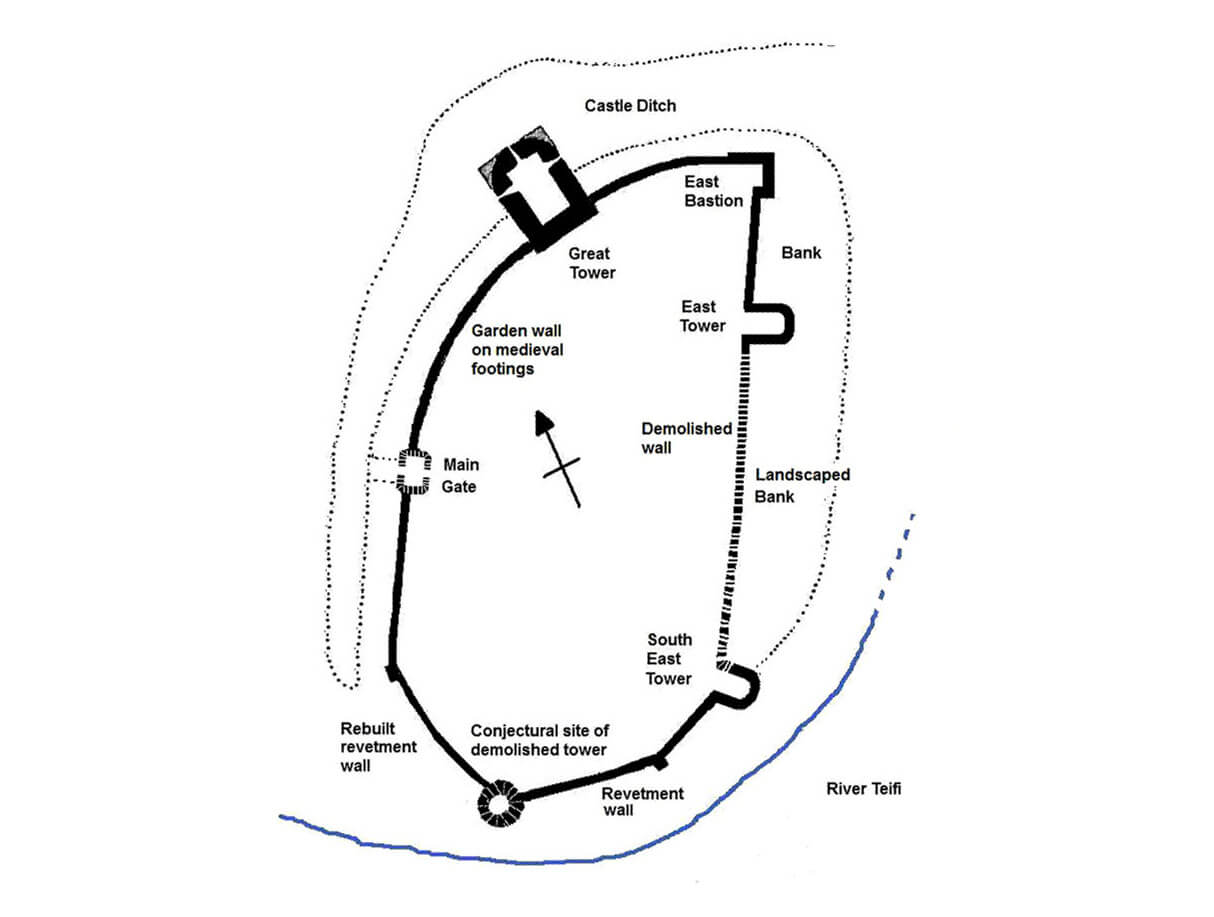

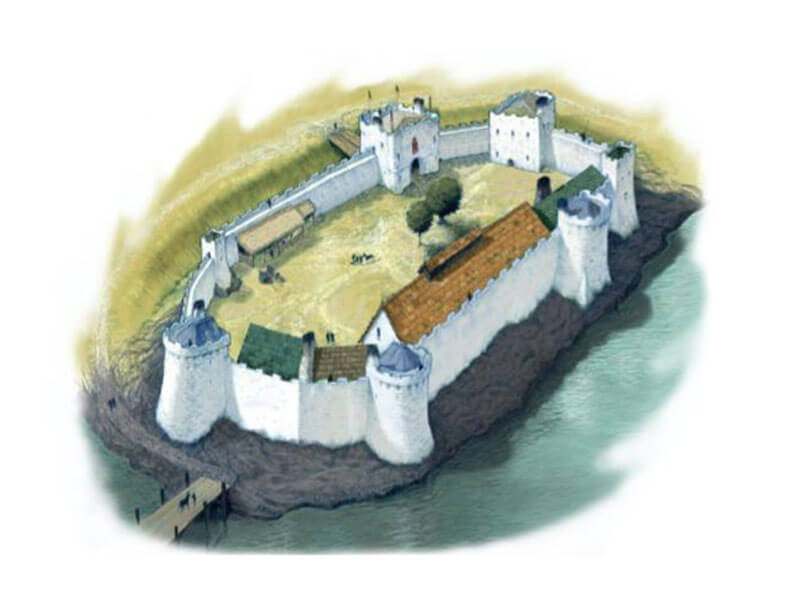

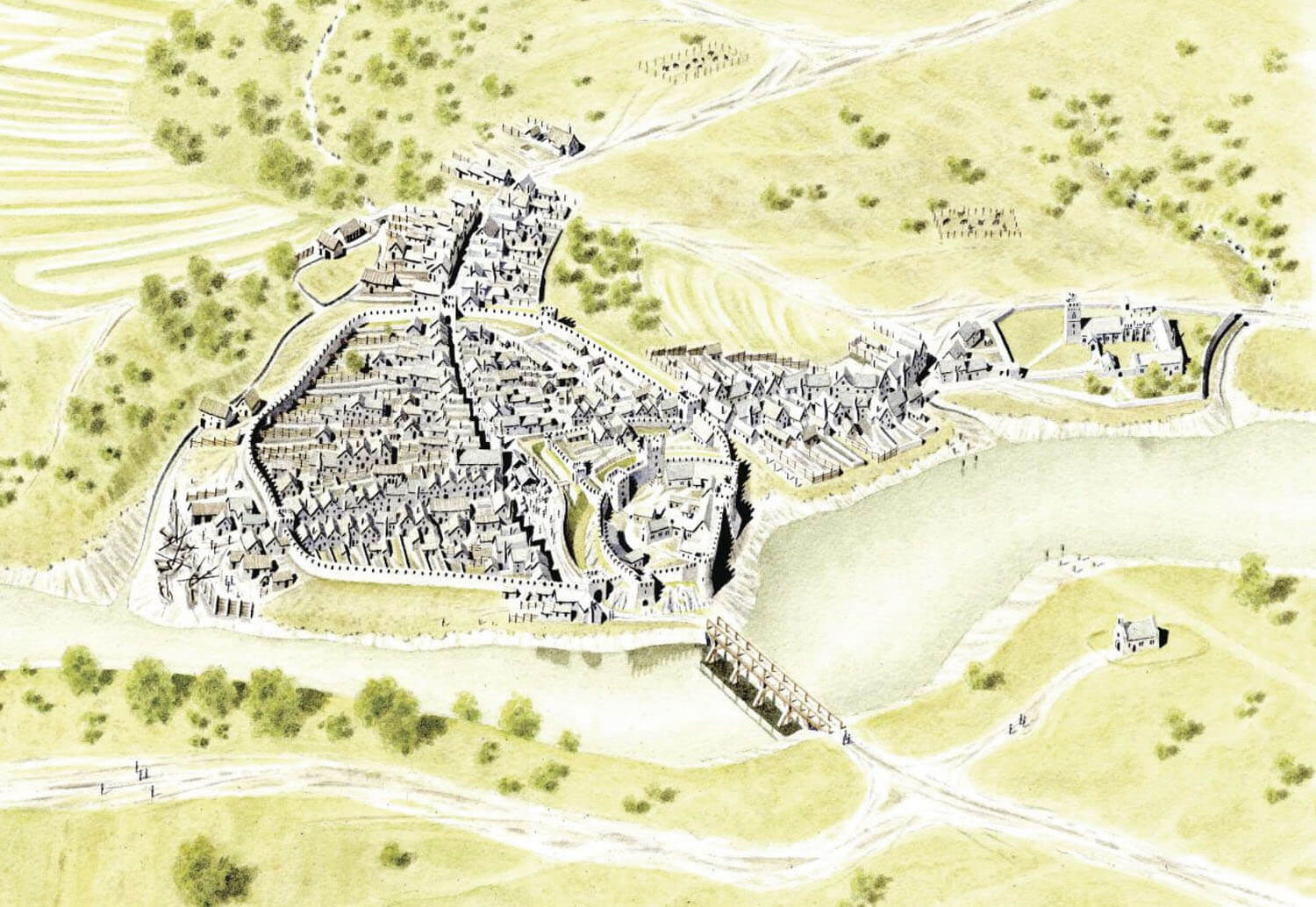

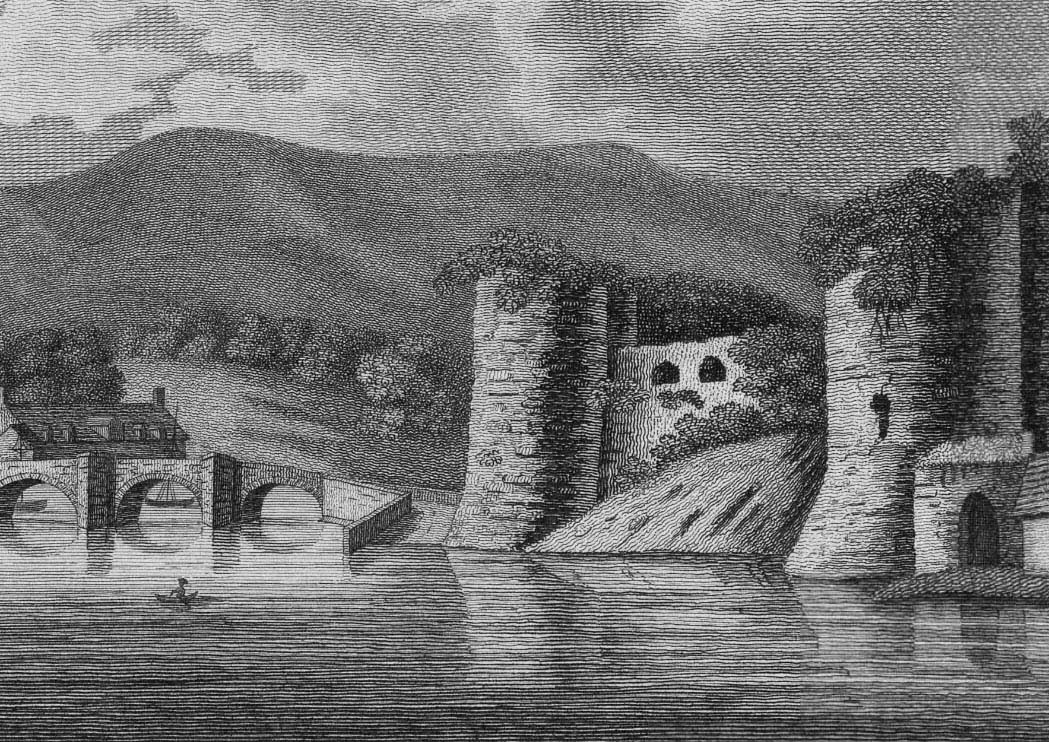

The castle was built on a rocky riverside outcrop, which ended on the southern and eastern sides with a low cliff above the water. On the only easily accessible sides, i.e. from the north and west, it was additionally secured by a moat. There, from the second half of the 13th century, it came into contact with two curtains of town defensive walls, covering an area of approximately 250 x 250 meters and accessible through four gates. The entire complex was limited from the west by the Mwldan stream, used for the operation of water mills and flowing into the Teifi River at the suburban fishing settlement. Unfortified suburbs developed over time from the north and east, with the church of St. Mary, Benedictine priory and Maudlyns Hospice located on the eastern side. There was a river crossing to the south of the castle.

In the 13th century, the castle consisted of a single circumference of defensive walls, closing an oblong-shaped courtyard with a clearly cut northern corner, measuring approximately 90 x 47 meters. The northern part of the inner ward could be divided by an internal wall, separating a smaller courtyard with a shape similar to a triangle. The castle’s utility and auxiliary buildings were concentrated in the castle’s outer bailey, located on the northern side of the main part of the castle. The outer bailey bordered the town on two sides, while on the third, eastern side it faced the forelands and suburbs.

The main element of the castle was to be the so-called Great Tower, i.e. a keep on the plan of an elongated horseshoe with massive spurs-buttresses in the ground floor, located in the northern part of the castle and fully extended in front of the perimeter of the defensive walls. Such an unusual location and shape would rather indicate that the tower was originally part of a massive, two-tower gate complex, which does not exclude that, like other buildings of this type, its upper storeys served residential functions.

From the east, the Great Tower was adjacent to a corner four-sided tower (perhaps opened from the inside) and a semicircular tower. The latter was built around 1244 and was unique because of the two side passages leading down to separate latrines. The southern part of the castle was defended by a semicircular tower and a cylindrical tower. The main entrance gate, if it was not on the site of the Great Tower, was on the west side. It is not known what form it had, perhaps it was a very popular construction at that time, consisting of two flanking towers.

Current state

Until now only the southern part of the defensive wall with a partially preserved semicircular tower has survived from the castle, significantly transformed in the 19th century. The partially preserved two eastern towers and the lower, rebuilt part of the keep with batter are also visible. In recent years, renovation works have been carried out on the monument, which was opened to visitors in 2015. A restaurant, hotel, open-air concert hall and a heritage centre with educational facilities have been opened there. There are no traces of the medieval development of the outer bailey and the town defensive walls visible on the surface today.

bibliography:

Davis P.R., Castles of the Welsh Princes, Talybont 2011.

Davis P.R., Towers of Defiance. The Castles & Fortifications of the Princes of Wales, Talybont 2021.

Morgane G., Castles in Wales, Talybont 2008.

Poucher F., Cardigan, Llandeilo 2010.

Salter M., Medieval walled towns, Malvern 2013.

Salter M., The castles of North Wales, Malvern 1997.