History

The settlement of the hill above the Tērvete River began in the 1st century BC. Around the 1st century AD, the first hillfort burned down and new ramparts were built in its place, additionally reinforced around the 4th-5th centuries AD. The stronghold was then inhabited continuously until the 10th century, after which around 1000, the largest construction works began in Tērvete on the fortifications, which were next modernized in the first half of the 13th century.

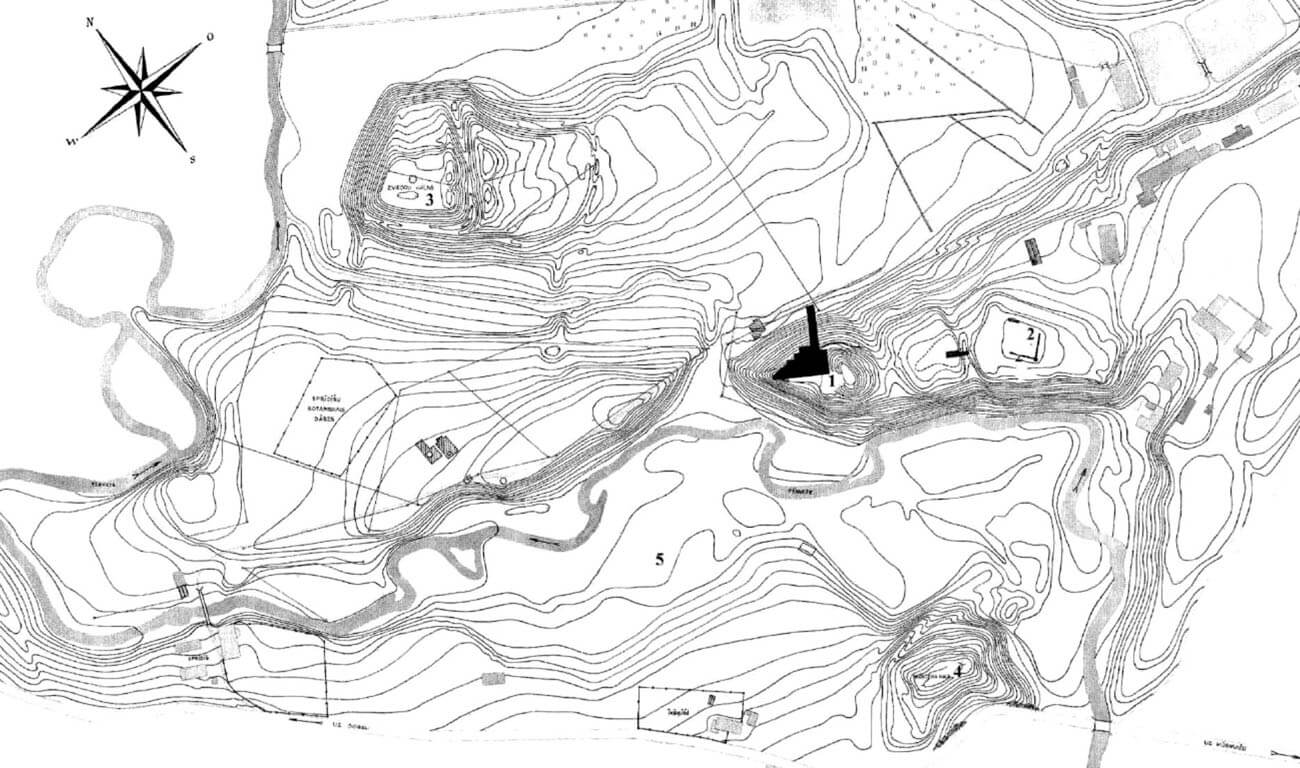

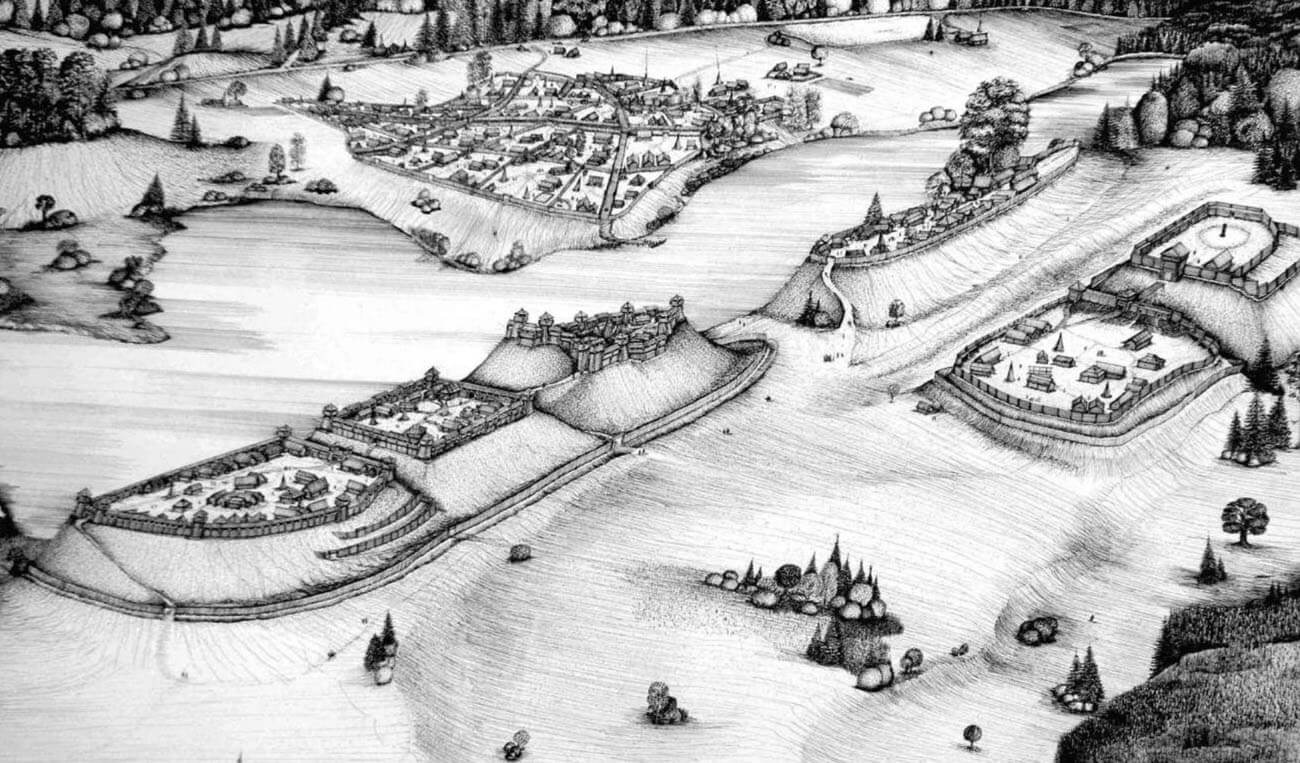

Tērvete was first recorded in 1219. At that time, it was the political and economic center of the western part of the Baltic tribe of Semigallians, with a hillfort and settlement ruled by Prince Viestard (“Viesthardus”, “Westardus”, “Vester”), and later Nameisis (“Nameyxe”, “Nameyxe”) and possibly also Šābis (“Schabe”). In the agreement between the Archbishop of Riga, the Livonian Order and the city of Riga on the division of Semigallia in 1254, six regions were recorded: Sillene, Sagara, Dubene, Sparnene, Dubelone and Thervethene. The latter was then a magnificent settlement complex, consisting of several strongholds, neighboring settlements and a fortified cult hill, in addition to the hillfort.

In the first half of the 13th century, the Semigallian lands became the target of raids by the Livonian Order, a German knightly order founded in 1202. In 1236, together with the Samogitians, they managed to inflict a heavy defeat on the knights in the Battle of Šiauliai, but the Livonian Brothers of the Sword were saved by a Teutonic Knights contingent and the union of both orders in 1237. In 1280, the Semigallians themselves burned the Tērvete outer bailey, protecting themselves from the Teutonic Knights in the main part of the hillfort, but the construction of a castle by the knights in 1285 in the vicinity of the stronghold forced the Balts to leave Tērvete five years later.

In 1338-1339, Master Eberhard von Monheim from the Livonian branch of the Teutonic Order ordered the stronghold to be rebuilt, probably to protect from Lithuanian military expeditions. In its place, a stone castle called Hofzumberge was built, directly subordinate to the Dobele commanders. Already in 1345 it was captured by the Lithuanians of Algirdas Gediminas, who killed eight knights of the Teutonic Order and a large number of other people. The castle was rebuilt only in the 16th century for the purpose of princely hunting lodge, where in 1596 Gotthard Kettler’s sons, William and Frederick, concluded an agreement dividing the duchy of Courland and Semigallia between themselves. The Hofzumberge was destroyed and abandoned during the Great Northern War in the early 18th century.

Architecture

The stronghold was built on the edge of a vast, elongated hill, protected from the south by the wide and deep Tērvete River. This headland, after being slightly widened by the first settlers, had a roughly triangular shape in plan, with three sides limited by steep slopes of a height of 17 to 19 meters. It is possible that the first widening of the headland, carried out with a mixture of sand and coal, was the result of clearing the hill of forests or bushes by burning them. The next enlargement at the beginning of 1th AD was caused by pushing the burnt structures of the oldest fortifications down the slopes. This process was repeated to a greater or lesser extent until the 9th-10th centuries, which finally increased the area of the headland to dimensions of about 50 x 35 meters. On the eastern side, where the promontory connected with the rest of the hill and two outer baileys, a transverse ditch about 8 meters wide was made, from which the excavated earth created a rampart. Together with the ditch it formed a slope 10-12 meters high on the eastern side.

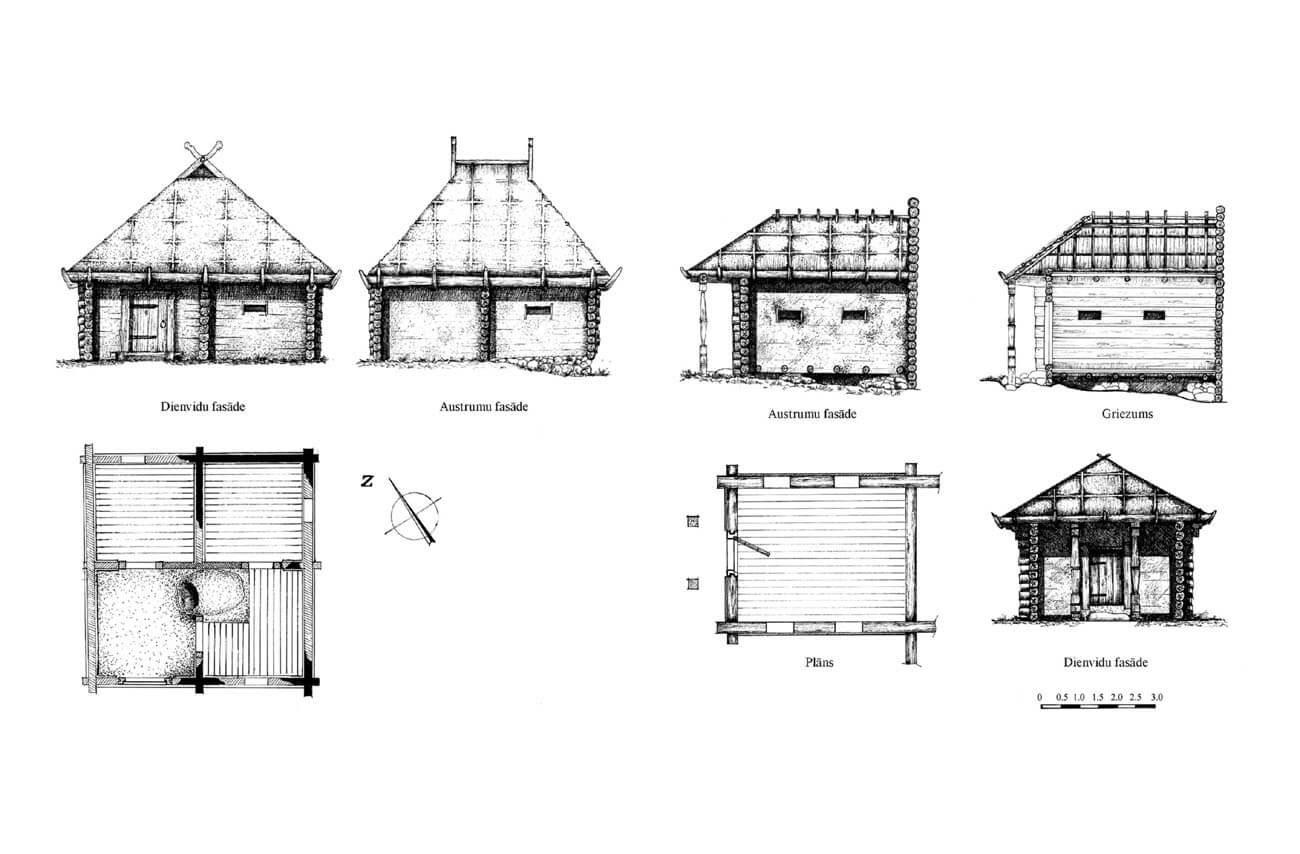

The oldest fortifications of the hillfort consisted of vertically driven posts, about 60-70 cm in diameter, arranged along the slopes, every 2 meters, between which there was a wooden palisade structure. It could had the form of a single wall between pairs of vertical posts or two parallel walls filled with clay, sand and stones, over which a wall-walk was led. The whole could have been covered with a layer of clay to protect against fire. Similarly, the fortifications from the 1st century AD consisted of wooden posts reinforced with stones, between which there was a palisade covered with clay. The fortifications used until the 9th-10th centuries were probably of a similar form.

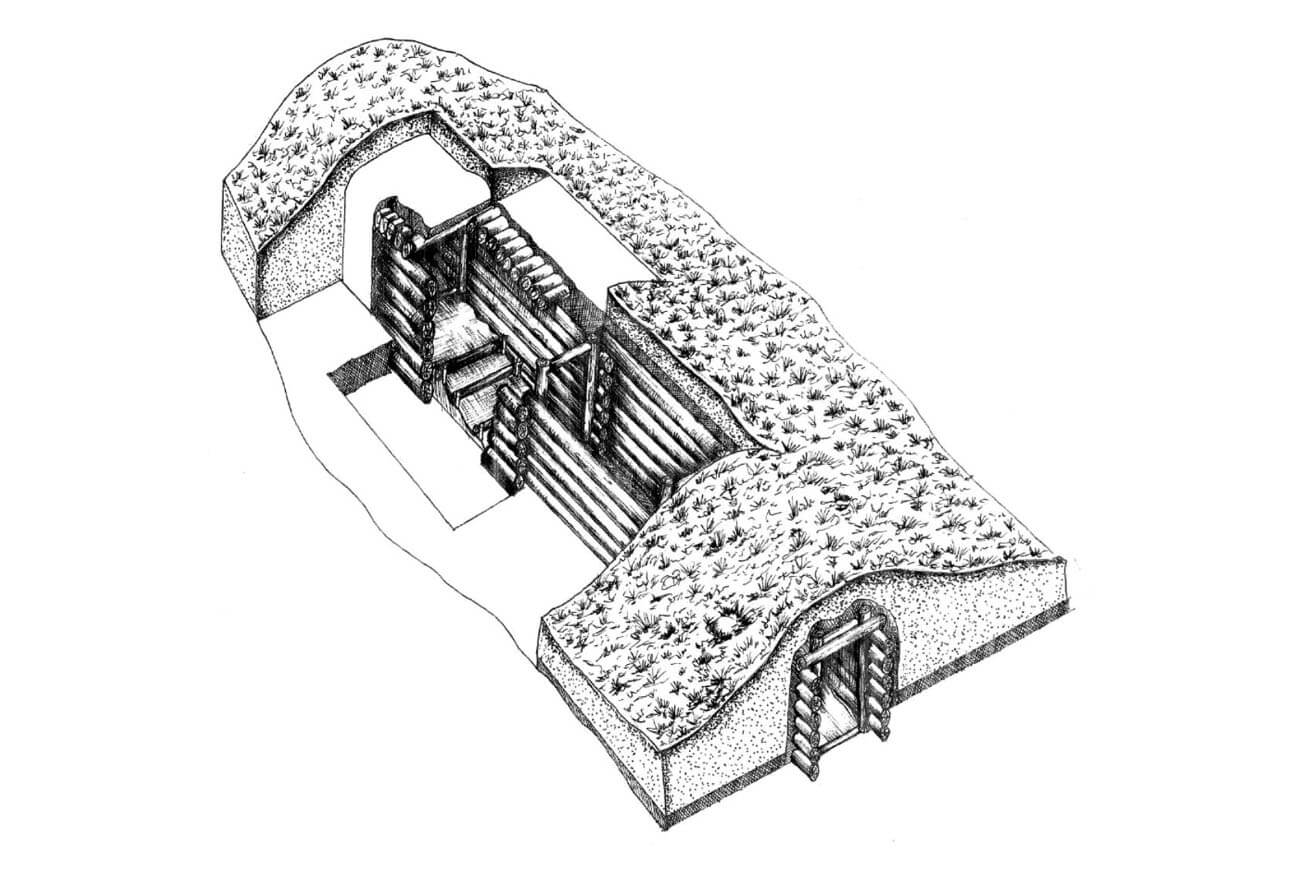

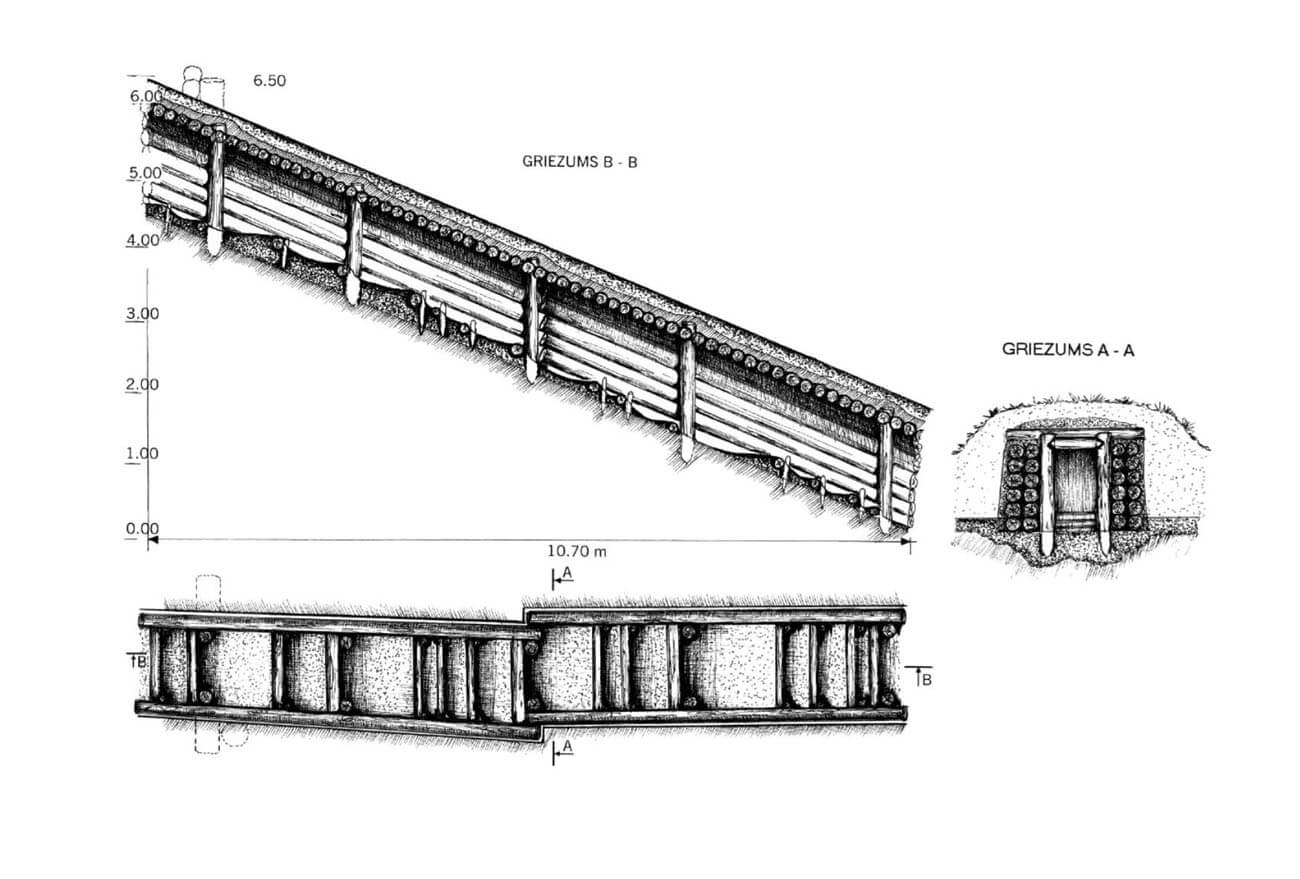

A particularly interesting structure, associated with the oldest stronghold fortifications, was an underground tunnel created on the hill from around the 4th-5th century. It led diagonally from the northern slope, under the perimeter of the fortifications, southwards to the flattened part of the hilltop. Its width was about 1 meter, and its total length was about 11 meters. The walls were made of horizontally laid logs and reinforced with vertical posts. The tunnel ceiling was covered with a wooden structure covered with birch bark and clay. The height of the ceiling from the ground was small, only 1.2 meters. To facilitate movement through the underground passage, steps were created in the initial part of the tunnel. The structure could have served as a unique postern gate, perhaps leading towards a well.

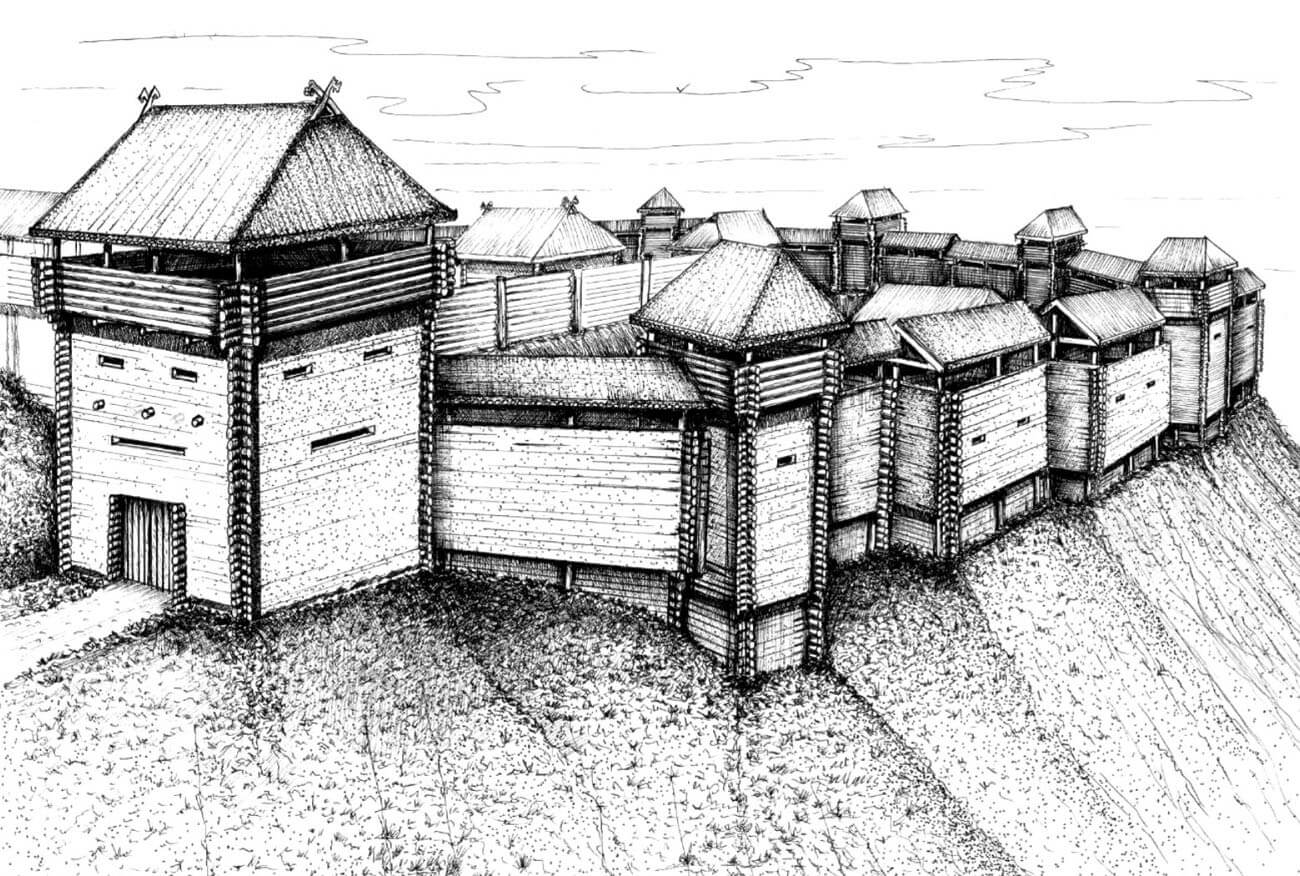

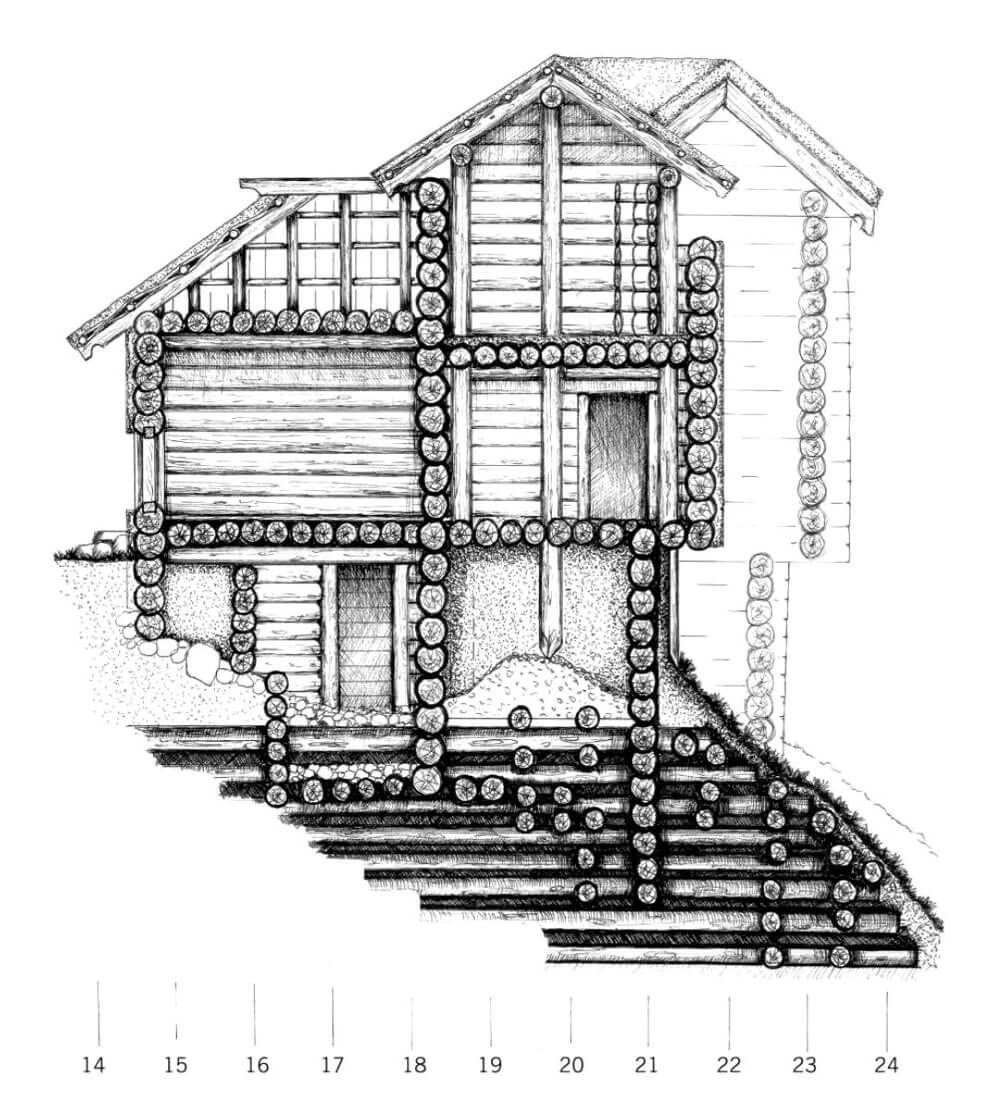

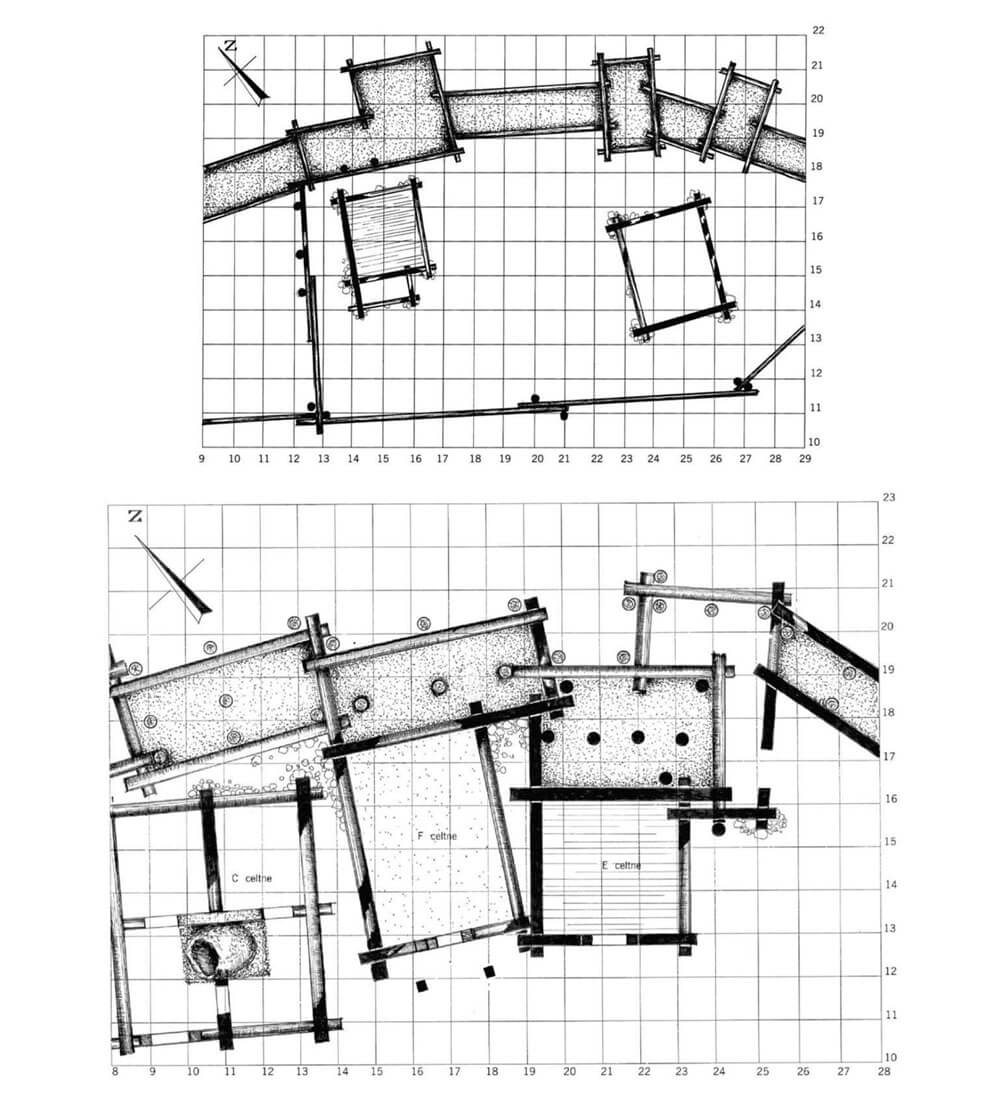

At the beginning of the 11th century, the hill area was expanded to its greatest extent when an approximately 8-meter wide terrace was created on the northern slope, the base of which contained wooden chamber structures filled with stones, clay and earth, placed approximately 1-2 meters below the level of the courtyard. Moreover, at the foot of the hill, a water-filled ditch was dug, 0.7-0.8 meters deep and 1.2 meters wide. On the terrace, the defensive buildings were located on a compact clay embankment, approximately 1 meter higher than the economic buildings of the courtyard. The stronghold’s fortifications had the form of log-built boxes, 2-4 meters wide and of various lengths, up to approximately 7 meters long, which were covered with clay from the outside to provide the walls with fire resistance. Unlike other parts of the stronghold, the chambers of the fortifications on the terrace were not inhabited, but larger residential and utility structures of log, half-timbered and posts constructions were added to them from the courtyard side. Probably only the upper storeys of the ramparts were used for defensive purposes. After being burned down in the 11th century, the chambers-boxes that formed the defensive perimeter were built narrower, about 1.3 – 1.8 meters wide. The stepped layout was also abandoned in favor of chambers arranged in a more regular arch.

The log-chamber perimeter of the fortifications was reinforced in the mid-13th century with numerous projections protruding towards the foreground, which probably had the form of towers enabling mutual flanking. They were set on stone foundations and raised higher in a log construction. To a lesser extent, they also protruded in front of the perimeter from the courtyard side. Towers were probably topped with roofs supported by vertical pillars, in the final phase of the stronghold covered with clay tiles. The height of the first floor was 2.5-3 meters, and the total height of the fortifications could have reached about 6.5-9.5 meters, with the towers estimated to be about 3 meters higher than the wall-walk. The gate was located on the north-eastern side, in a large quadrangular structure measuring 4 x 6 meters, probably of a tower-like form. Inside the hillfort in the 13th century, the highest core of the complex was separated by a palisade, based on pairs of posts dug into the ground, spaced 1-1.5 meters apart. It may have separated the type of underwall road that the defenders could use or the road that was an extension of the entrance gate.

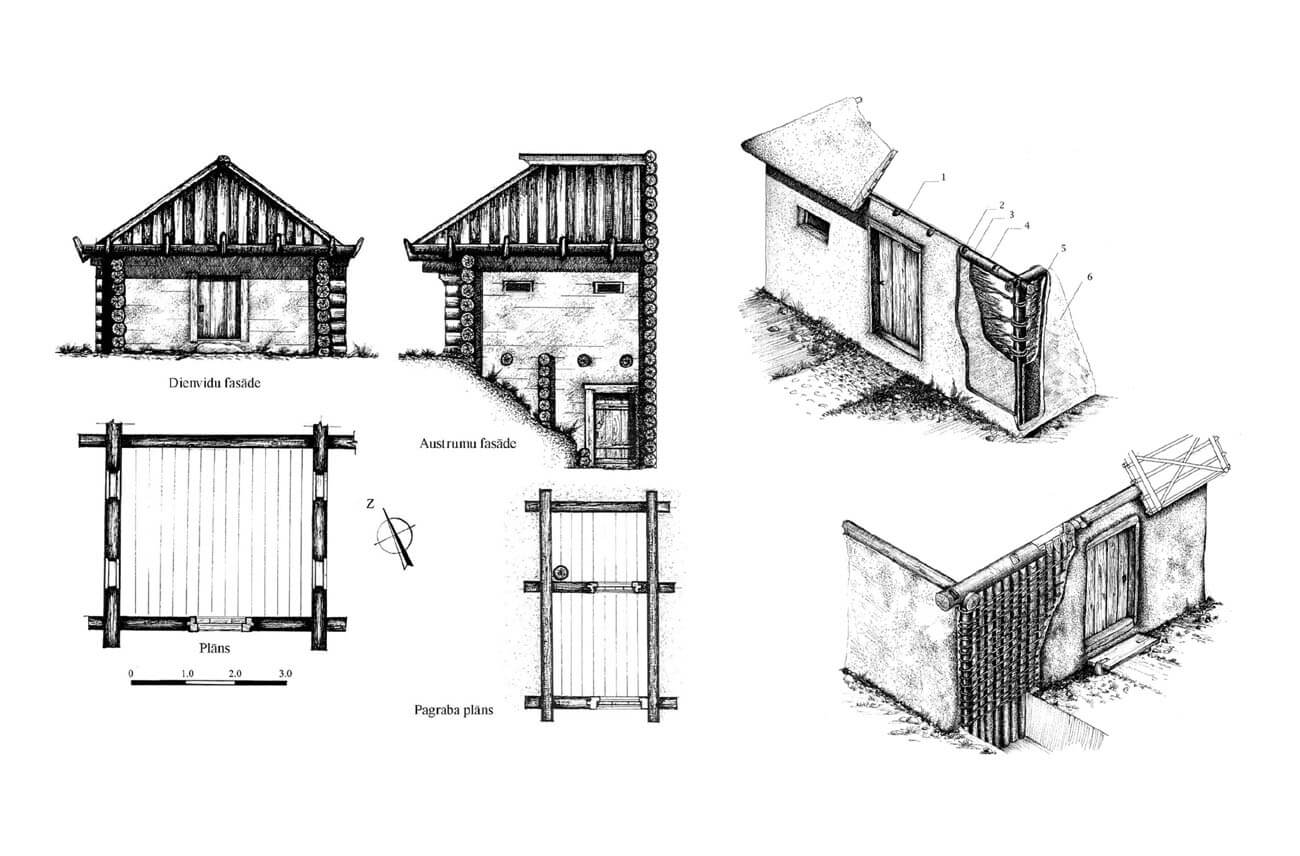

The stronghold’s residential and economic development from the 11th to 13th centuries was dense, both in the courtyard and on the artificial extension of the northern terrace. The houses were built primarily in a log construction, i.e. from horizontally laid logs that were connected at the corners. The post and half-timber technique was also used. The houses were single-space, although some had two or even four rooms. The external elevations were covered with clay, in some cases also whitewashed. The floors were made of clay or of chipped or hewn boards, sometimes nailed. Wooden roofs were covered with birch bark and clay. In the final phase, similarly to the fortifications, clay tiles were also widely used. Iron U-shaped clamps were commonly used to secure the structural elements of buildings, probably used mainly in roof structures. It is possible that some buildings had upper storeys, as their foundations were reinforced with piles of stones. In addition, there were cellars for food and drinks under some buildings. The interiors were heated by clay dome ovens, and later also by stone and brick ovens, located most often in the corners of the rooms.

In the 13th century, the area of the two baileys on the eastern side of the main part of the stronghold was also fortified with log fortifications. Similarly like the inner bailey from the main hillfort, the outer bailey was also separated from the inner one by a transverse ditch. The medieval settlement complex also included two hills on the north-western side, separated by a deep ravine, one about 12 meters high, the other about 20 meters high. Initially, they served as a tribal cult site, but were fortified no later than in the 13th century. In addition, to the south-west of the Holy Mountain and about 20 meters to the west of the hillfort, a narrow and elongated elevation of about 12-15 meters in height was secured by light fortifications. On the opposite bank of the river, a large, open or lightly fortified settlement of about 10 hectares developed.

The Teutonic castle was built on the eastern edge of the hill. It was situated in a place originally occupied by the outermost bailey of the Semigallians’ hillfort, which is why the Hofzumberge was separated from the narrowing headland of the hill by a transverse ditch from the west. The castle was built on a square plan measuring 25 x 25 meters with defensive walls 1.1 meters thick. At least one of the corners was equipped with a quadrangular projection of the wall in the form of a massive buttress or a small tower. Inside the perimeter, near the south-eastern wall, there was a residential building with a basement.

Current state

Today, there are no traces of buildings visible to the naked eye in the main part of the hillfort, but a transverse ditch and an earth rampart separating the stronghold from the bailey are still visible. However, several fragments of the perimeter wall of the Teutonic castle have survived to the present day in the former eastern bailey, including one longer section of the former southern wall, the southeastern corner and part of the eastern wall. In the preserved fragments, there are visible openings of early modern windows and openings from ceiling beams. A few hundred meters from the stronghold, on the opposite side of the P103 road, you can see a modern reconstruction of the wooden early medieval fortifications of the Semigallians.

bibliography:

Borowski T., Miasta, zamki i klasztory. Inflanty, Warszawa 2010.

Herrmann C., Burgen in Livland, Petersberg 2023.

Jērums N., Tērvetes pilskalna aizsardzības konstrukcijas un ziemeļu terases apbūve, “Arheoloģija un etnogrāfija”, 28/2014.

Jērums N., Tērvetes pilskalna apbūve 11. – 13. gadsimtā, “Arheoloģija un etnogrāfija”, 29/2016.

Vitkūnas M., Zabiela G., Baltic hillforts: unknown heritage, Vilnius 2017.